Junk Explained: Why “Free Range” Eggs Aren’t All They’re Cracked Up To Be

Your eggs may have been lying to you. But there are a bunch of tools you can use to find out more about what you're eating.

It’s been an egg-citing week at the supermarkets (sorry), with Woolworths pledging to phase out battery hen eggs this morning, and advocacy group Choice taking a stand on free range claims.

Both announcements signal a move towards more ethical food consumption, and more honest labelling on egg cartons.

Because chances are, your eggs have been lying to you.

–

Cage vs Free Range:

I would never be caught buying cage eggs. It’s not just because I care about what the shoppers at my community market think of me; I am one of the many people who pay extra because I care about the conditions of chooks.

Generally, I will pay more than double for free range eggs. Research by Choice shows that the average cost of cage eggs is 43 cents per 100 grams, compared to free range eggs at 93 cents per hundred grams.

Free range eggs allow people to make a choice about the quality of life for animals in food production. Free range hens are meant to have space to move and exhibit natural bird behaviour, as opposed to the cramped and sometimes cruel conditions for caged hens.

The problem is, producers and advertisers use multiple definitions for “free range” eggs, all with different rules about how much space Hennie the Hen gets for her nest. According to Animals Australia, these are the labels you want to look out for (although the RSPCA certification can also be found on barn-laid eggs; make sure the label says free range, too):

The Victorian-based Free Range Farmers Association’s certification is one of the strictest in the country. Farms with this certification are independently audited, and can’t keep more than 750 hens in a hectare. Lots of space for the Charleston.

At the other end of the scale, the Coles “free range” label allows for 10,000 hens per hectare. Even though hens aren’t kept in a cage, they’re essentially treated like this:

The Australian Egg Corporation Ltd (aka the group representing large industrial producers, aka “big egg”) thinks that free range should be defined as 20,000 hens per hectare. The number seems ridiculous, until you learn that some “free range” farms are keeping 30-40,000 hens per hectare. Which is up to 4 hens per square metre. Which is a lot of hens.

Some farmers are abandoning the free range label because they don’t want to be associated with the way larger companies use, or abuse, the term. We’re starting to see a range of confusing alternative phrases on egg cartons, like “field fresh” or “genuine free range” or “free to roam.” It’s extremely difficult to determine whether a label is using PR chicken-shit, or making an honest claim.

Free Range Does Not Mean Cruelty Free

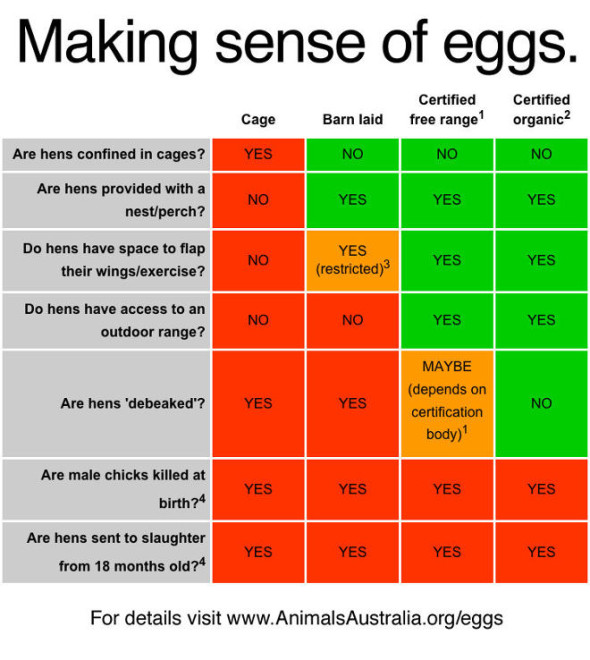

You could take “free range” to imply that hens are kept in a cruelty free environment. But while physical space to roam is an important part of hen welfare, there are other industrial practices that can occur at a “free range” farm that you might consider cruel. These range from debeaking (where the end of a hen’s beak is burnt or sliced off, to prevent harm to other birds in crowded conditions), to killing all male chicks at birth because they have no use in this particular part of the animal industry.

Animals Australia has provided this guide for major egg types. It’s generally accurate, but you need to investigate the conditions behind each label for specific information:

Numerous advocacy groups are putting pressure on governments and regulators to set clear definitions for free range eggs. Consumer advocacy organisation Choice is leading the charge, submitting a “super-complaint” to NSW Fair Trading calling for an investigation into whether free range claims are misleading. Also in NSW, Greens MLC John Kaye is calling for a Parliamentary Inquiry into label accuracy.

Action is mostly concentrated at a state level. Even if progress is made, you’re likely to see different standards for free range eggs across the country. A national, enforceable definition of “free range” eggs is still a long way off. For now, it’s up to you to unravel the marketing claims.

What Can You Do?

If you want to support free range, you’re going to have to do the research on each brand. Some companies are brilliant, others terrible, and there’s a lot that could do better but are on the right track. Here’s a shortlist of questions to consider when rating your eggs:

- What’s the hen stocking density? (i.e. How many hens per hectare? The less hens per hectare, the better.)

- Do hens have constant or partial access to outdoor areas?

- Does debeaking, wing clipping or toe trimming occur at the farm?

- Does the farm use antibiotics or growth hormones?

- Are farms independently audited? (i.e. Can they get away with claiming that they’re something they’re not?)

To find an egg that fits with standards of hen welfare you’re comfortable with, use the Animal Welfare Labels website. You can find specific information about conditions for most egg brands.

By purchasing free range eggs produced with higher quality hen welfare, or by purchasing any other ethical product, you encourage “good” behaviour from producers. As a consumer, you can use your purchasing decisions as a protest vote.

For help with finding all kinds of ethical products, the Shop Ethical app is brilliant. There’s also an exciting new consumer organisation, Otter, which wants to connect people with better products. They’ve just started a regular newsletter to keep you up-to-date with developments in ethical shopping.

Finally, if you want to opt-out of eggs completely, fuck yeah. You’re a stronger-willed person than most. A vegan diet can be super-healthy, but you need to plan meals carefully.

Do not live exclusively on hot chips. Tempting though that may be.

–

Erin Turner has a background in public policy and campaigns for consumer advocacy organisations. She considers herself an expert at writing angry letters. When not ranting at work, she rants at @iserinleigh

Feature image via Wikipedia.