With ‘Jessica Jones’, Will Marvel Actually Make A TV Show About Sexual Abuse?

The on-screen Marvel universe isn't known for nuanced plotlines about gender and abuse. So how will they tell this story?

This piece deals with Marvel series Alias; as such, it may contain potential spoilers for Netflix’s Jessica Jones.

–

There will come a time when a new piece of Marvel-branded entertainment is delivered on the hour. The rare days where there’s no new missive from the Universe will be like public holidays – annoying that you can’t get what you want when you want it, but a nice opportunity to actually go outside and sit under a tree.

On November 20, Netflix will drop its brand new original series, Jessica Jones. Based on a comic book series, the show forms part of streaming service’s street-level super heroes package; though connected to the wider Marvel film and television universe, we were promised these offerings would be a little more mature. Darker. More violent. And Daredevil certainly delivered on that.

Now comes a show about a female private eye who, yes, has super-powers — but who also has a traumatic past, drinks to excess, and has, reportedly, casual and rough doggy-style sex.

We’re a long way from Spiderman’s rainy upside down kiss.

–

How Much Of Alias Will Be In Jessica Jones?

Jessica Jones is based on the comic book miniseries Alias, which ran from 2001 to 2004. Written by Brian Michael Bendis, with art by Michael Gaydos, it follows Jessica, a private investigator working in New York City. She has a degree of super strength, though it’s untested, and the ability to fly (though she’s shaky on the landings). She has the requisite street smarts for the job — a lot of which translates to knowing how to Google the name or phone number of a missing person to get some answers. She’s funny and compassionate, and, when in her comfort zone, she’s confident and sexy.

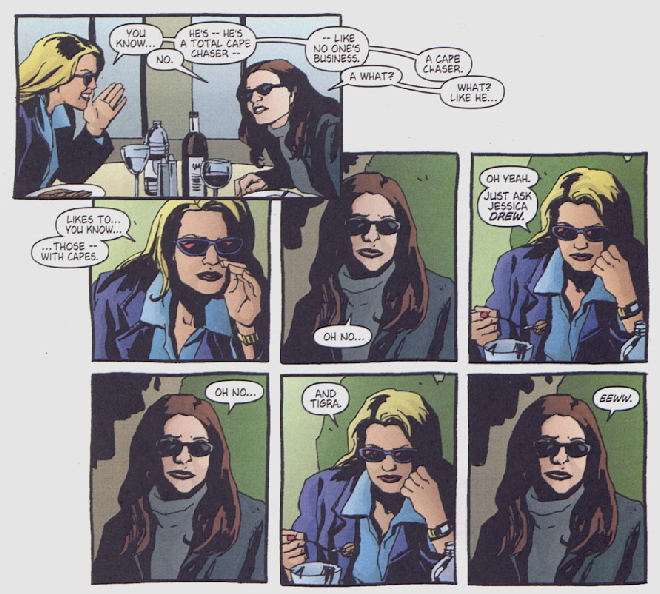

Jessica also, as mentioned, drinks a lot, often to a state of blacking out. She has a horrendous potty mouth, and she tends to have a lot of casual sex, as both an emotional release, and as a numbing device to deal with past traumas — traumas which we learn about slowly over the course of the series. Some of Jessica’s behaviour is played for laughs; hangover jokes are funny in any medium, and the look on Captain America’s big boy scout face when he hears a couple of f-bombs is great.

But Alias deals with sexuality and emotional abuse with a mature, nuanced touch that mainstream media, let alone superhero comics, rarely achieve.

–

How Will Netflix Tell This Story?

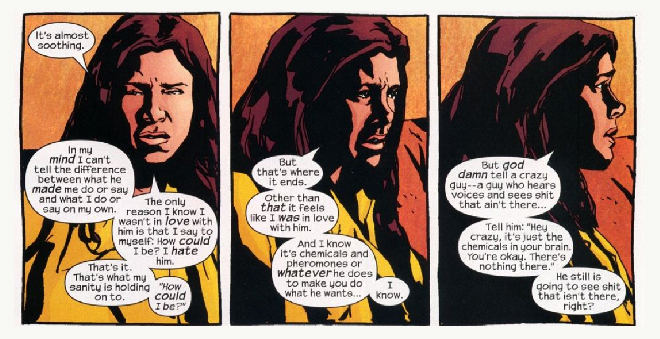

During the comic book series, it turns out Jones once moonlit as a superhero and, after a few minor successes, came under the sway of a villain with mental powers called the Purple Man. She spent eight months being controlled by him, and was forced to enact violence on others, and to beg for sex with him. Jessica can remember everything that happened, and also the feeling that she was truly in love with him through it all.

It’s the story of an emotionally abusive relationship, told through the metaphor of super powers. As a result, Jessica has a complex relationship with men, and sex, and trust, and herself. The question then is: how much of this subject matter will carry over into the new adaptation?

Of course, it would be far from the first time that a television program with magical or supernatural elements has dealt with difficult, dark topics; there are more think pieces about the way Game of Thrones uses rape as a plot device than there are ice zombie and dragon montages on YouTube. But Jessica Jones isn’t based on a property that most people already consider mature entertainment; this series takes place in the same universe as a talking racoon, a goofy shrinking dude, and the Avengers. It’s an all-ages, all-consuming, cross–platform, multi-billion-dollar entertainment monolith. It’s tough to imagine Marvel letting any of their precious costumed action figures play in Jessica’s dark, dirty, complicated adult sandpit.

Serious Business In The Funny Pages

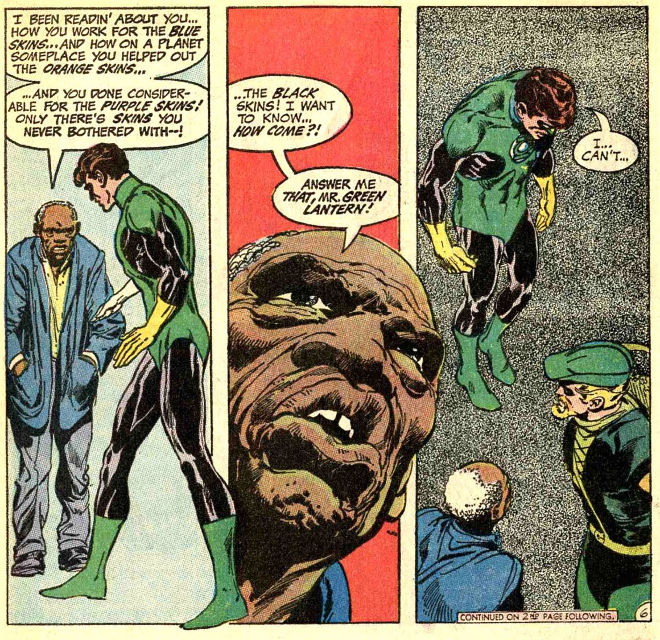

Super hero comics have long dealt with ideas beyond space crystals and gamma rays. In the ‘70s, Green Lantern and Green Arrow became social crusaders, battling against institutional neglect and drug addiction in impoverished communities, often realising there was no easy solution to these issues. Marvel went out of its way to make its heroes fallible and nuanced – Iron Man was an alcoholic, Ant Man was emotionally unstable and abused his wife, and Captain America quit his job due to disillusionment with the government’s handling of the Vietnam War.

The ‘90s saw a new style of comic book writing led by the two-hander of Alan Moore’s Watchmen and Frank Miller’s Dark Knight, both of which asked, “What does it say about your psyche if every night you dress up in a rubber body suit and punch people?”

This more serious, mature approach to the medium was quickly overtaken by gratuitous sex and violence, and — is so often the case — female characters bore the brunt of this vicious new world. Elongated Man’s charming detective partner and wife, Sue Digby, was raped. Starfire was raped and killed. Batgirl was shot in the spine. It doesn’t matter if you don’t know the characters; you can easily imagine how deeply unpleasant it would be to read these stories. So frequently were these extreme and heavy-handed plot developments used to give weight to male protagonists’ stories that a site was developed to keep track of the poor storytelling trope.

Alias directly addressed these issues, taking a character who is treated like far too many women in comics are, and showing the actual repercussions and the powerful recovery of her sense of self. The primary bad guy of the narrative is a scary purple dude, but the series also points the finger at secondary villain: the lazy, sexist traps comic book writers so often fall into

Marvel movies have come under fire for their treatment of female characters, as well they should. But Marvel movies should also be criticised because they are so often only about space crystals. Spiderman was first created as a way to explore puberty and adulthood, and the X-men as representative of how society treats minority groups; meanwhile, the last Marvel movie, Ant-Man, was about learning how to shrink good.

The trailers for Jessica Jones indicate that the abuse Jessica underwent, and her trauma stemming from it, will be a part of the story. If the show succeeds in telling that story as well as the comic series does, here’s hoping we start to see more Marvel properties with something interesting, and important, to say.

–

Jessica Jones will premiere on Netflix on November 20.

–

Matt Roden works at non-profit writing centre Sydney Story Factory, and co-hosts Confession Booth. His illustration and design work can be seen here.