Outsiders, Incompetents, Weirdos And Dreamers; Terry Pratchett Made Heroes Of Us All

"I was far from alone in feeling that Terry Pratchett changed my life."

No one is actually dead until the ripples they cause in the world fade away. – Pterry

–

Probably no author supplied the world with as many apposite quotes for use upon his death as Sir Terry Pratchett. Death was, after all, a permanent fixture in his Discworld series, popping up in every book to harvest the souls of the deceased, and occasionally taking centre stage himself. In Pratchett’s fantasy universe, Death was not a fearful or cruel figure, but one who simply got on with his job, viewing humanity with detached bemusement and a little sneaking affection; an aloof, unemotional figure with a weakness for cats. He represented the end of life, but was at the same time a rather lively part of it. Every time Death appears in a Pratchett novel, the author seems to be saying, it’s OK, you don’t need to be afraid, even Death is only human.

Being human was a central concern of Pratchett. Has anyone managed to write with such biting humour, such raucous absurdity, while simultaneously infusing every page with a warm, big-hearted humanity that never left any doubt in the reader’s mind that they, the author, and everyone else were together on this weird, tangled journey called life? To be a human being is to be a big awkward mess, and Pratchett made it his mission to get us all to embrace that, to laugh at it, and to love it.

Discworld, his greatest creation, began as a send-up of fantasy genre writing. The first Discworld novel, The Color of Magic, took a gleefully irreverent approach to tales of dragons and barbarians and Lovecraftian temples. But as the series continued, it quickly became so much more. Pratchett realised that his chaotically comic fantasy world, borne through space atop four elephants standing on a gigantic turtle, could be used not just to poke fun at a genre, but at the whole world.

And so Discworld grew and evolved and morphed into something vast and complex and strangely familiar. As the books themselves suggested, our own world was forever seeping through the porous boundaries between reality and fantasy. That’s why Discworld concerned itself not with traditional sword-and-sorcery escapades, but with the troublesome confusions and painful struggles of our own universe, transplanted into a realm of wizards and trolls. In Discworld, Pratchett’s characters grappled with religion, politics, racism, feminism, technological advance, and economic theory. Discworld inhabitants coped with the intrusions of rock‘n’roll, the movies, mass communication, fiat currency and a free press. Pratchett had managed to provide an escape from the drudgery of the real world that commented on the real world at the same time.

And his heroes were real-world heroes. Outsiders, incompetents, weirdos and dreamers took the lead in his stories: people whose outlooks on life caused them to live at a forty-five degree angle to the rest of the world; folks who couldn’t help but try to make sense of things that didn’t make sense; who got into trouble by being different and got out of it the same way; who could change the world, or even save it, but would never rule it, because they wouldn’t conform to it. And in those heroes, we — his readers — saw ourselves.

Rincewind, the hopeless wizard who is sure there must be a better way to run the universe than magic. Granny Weatherwax, the stern witch who disdains those who believe in the supernatural without good reason, even when they happen to be correct. Sam Vimes, the eternally grumpy City Watch commander with a deep suspicion of all authority, even his own. Moist von Lipwig, the career criminal tasked with improving government services. Tiffany Aching, the young girl who learns witchcraft and rescues boys. And Susan, Death’s granddaughter, a reluctant heroine who considers the fantastic situations she finds herself in utterly ridiculous.

And of course so many others. Elegant assassins, devious businessmen, blockheaded warriors, scatterbrained wizards, sadistic elves, sarcastic dogs, militant zombies and demented monarchs and more, marching through the pages like an army of beautifully orchestrated lunacy.

Naturally it wouldn’t work unless the world spinning on top of those elephants was in the hands of a master wordsmith. Few writers could weave Pythonesque comedy, quicksilver satire and hoary puns together with heartfelt emotion and true dramatic tension so deftly – few would even try. But Terry Pratchett had an astonishing ability to make the story silly and real at the same time. The Patrician of Ankh-Morpork is called Vetinari – named for a throwaway pun and still as indelible and fascinating a character as was ever committed to the annals of fantasy. Never did Pratchett allow himself to believe that fun was incompatible with meaning.

And meaning he brought to us. It wasn’t necessary to see the response to his passing for me to know I was far from alone in feeling that Terry Pratchett changed my life. As a writer, certainly: his wizardly way with words, his razor-edged yet generous humour, his light, precise touch, all inspired me creatively and pushed me to strive for that rarefied level of expression. Pratchett runs inevitably through everything I write; all that I create carries a little of him with it, and I cannot sufficiently convey how grateful I am to him for that.

But more: he changed me – and millions of others – as human beings. He was our company when we felt most alone, a comfort in distress, a font of wisdom and laughter at times when we were most desperately in need of both. His characters were friends, his manic Discworld a destination to head for whenever we needed reminding that our own world was stupid, hilarious, frustrating…but also, every now and then glorious – for a world that produced Terry Pratchett must be so. In the sad, often intolerable procession of life, the population of Discworld endured, and found joy, and we knew we could do the same.

Of course we knew him through his books, his fictions, and though they made us feel close to him, not many of us knew him as a man. But we surely knew enough to know he was a great one. Whether in fiction or reality, he stood up and spoke for what he believed in, he did not bow to inhumanity or cruelty, and he made the opportunity his talents afforded him count for something: he told his truth. In his later years he was stricken with an illness of what must be the most horrible kind for an artist and a mighty mind: an illness that would attack his brain and cripple his thoughts. He faced the illness with calm practicality, acknowledging the dreadfulness of the circumstance, but refusing to abandon his love of life even as he prepared himself for its completion. And even in these frightening days, he made use of his situation to speak out, to make his beliefs heard and clarify to the world that he would never give up his right to his own identity, to his own dignity – and that nobody should have to. In the darkest hours, he fought for himself, and for everyone else: he remained, as ever, on the side of humans, those awkward messy creatures he spent his life studying, examining, mocking, and loving.

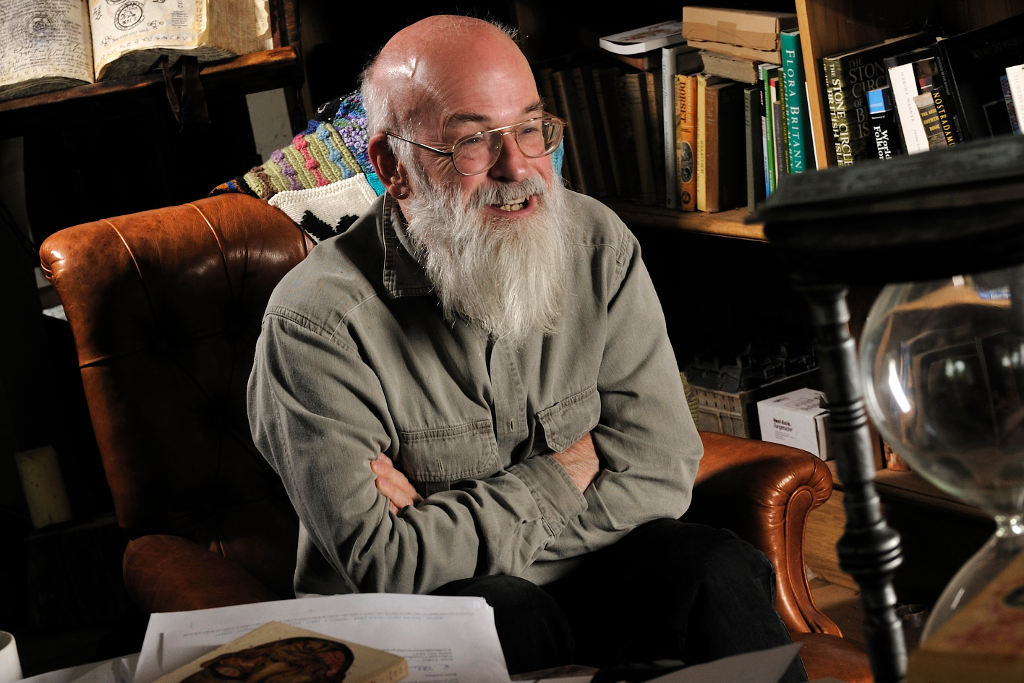

Photo via Dementia Friends.

He changed the world, and he did it with jokes and love and wisdom. He was the greatest Discworld character of all. Thank you for being there, Pterry.

–

Feature image by SFX Magazine, via Getty.