Junk Explained: Here’s Why Opinion Polls Aren’t As Important As People Think

Two polls out today, with wildly different results. How?

Two opinion polls were released overnight. Both asked voters whether they preferred the Labor or Liberal parties, and both got wildly different results.

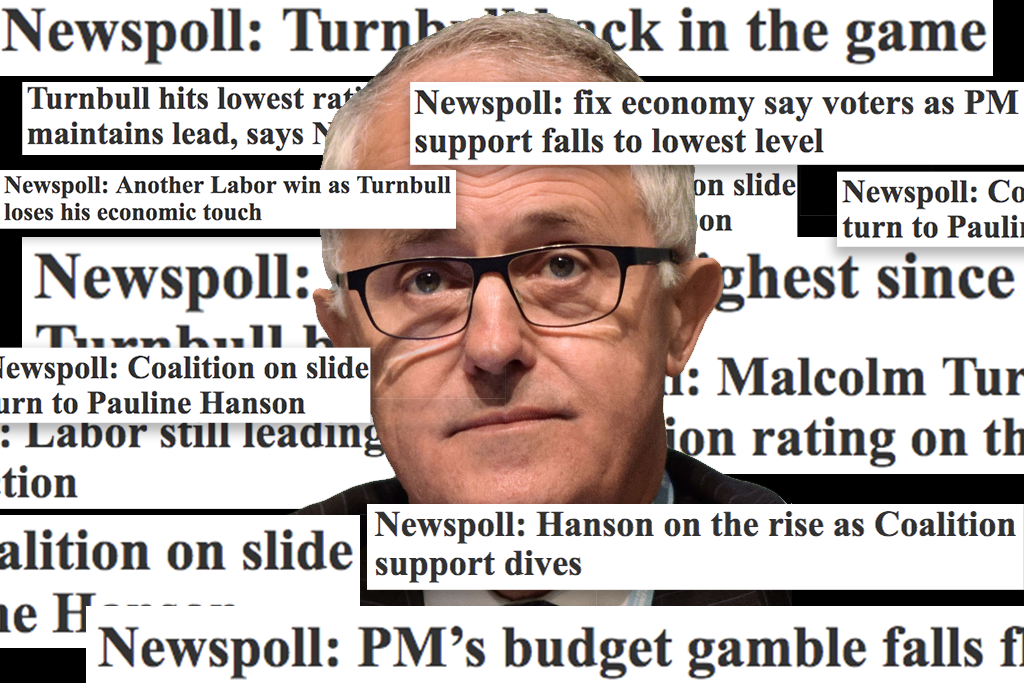

Newspoll, published by News Corp, had Labor up 51-49, while the Ipsos poll published by Fairfax showed Labor with a strong 54-46 lead. Both polls suggest Labor would win an election if one were held today, but the Ipsos poll has them winning 95 seats, while Newspoll has them winning only 80.

And while Newspoll said eight percent more voters now preferred Malcolm Turnbull to Bill Shorten as prime minister, Ipsos said nothing had changed since they last surveyed the public.

Why Do The Polls Come Up With Such Different Results?

Jill Sheppard, a political scientist from the Australian National University, told Junkee that the answer had to do with the polls’ methodology: that is, the particular ways they survey voters to get their results.

But there’s a problem — we don’t really know what method Ipsos and Newspoll use.

“A lot of the finer points of the major polling companies’ methodology is pretty opaque,” Sheppard explained. “We know that Newspoll uses a combination of phone and online surveys, while Ipsos uses phone surveys only.”

Sky News political reporter @samanthamaiden: My concern with latest Newspoll result is that it doesn’t mean anything unless people actually change their vote.

MORE: https://t.co/t7wrytwg83 #headsup pic.twitter.com/Uveq0HBjSQ

— Sky News Australia (@SkyNewsAust) May 13, 2018

Sheppard reckons that, in the end, it doesn’t matter how these polling companies get their data. Instead, what they do with it is the most important part of the process.

“Polling companies never report the raw data that they get from these surveys. Instead, they just adjust the raw data,” Sheppard continued.

This is where big changes can happen. If Ipsos only uses phones to conduct their survey, they wouldn’t naturally get a good balance of opinions: millennials use mobile phones heaps, and older, more conservative voters are more likely to answer a landline.

To correct for this, polling companies give “additional weighting to the responses of Australians who tend to be underrepresented in polls, such as young people, the less educated, and people without landline phones”, as Sheppard explained.

And because Australia has preferential voting, polling companies also make some of their own judgements about how votes will flow in an election. For example, Newspoll changed the way it allocates One Nation preferences earlier this year, giving the Coalition a boost in the polls even though nothing material had really changed.

The Image Problem

That’s not all that influences polling companies. Like any other company, pollsters worry about their bottom line: no one company wants to get an election wrong, so to hedge against any risk, polling businesses sometimes create results that are close to other pollsters.

“No one company wants to be an outlier. If, say, Ipsos is the only company to predict a Coalition victory at the election and the Coalition gets thumped, then Ipsos’ reputation is damaged. If the Coalition happens to win, Ipsos will win some reputational prestige, but probably not as much as they stand to lose in the event of being wrong,” Sheppard said.

This polling company motivation was discussed in great detailed after Donald Trump’s surprise victory in the 2016 US presidential election. In many of the states Trump won, pollsters got their numbers wrong.

One of them, Berwood Yost from Franklin & Marshall College, told Five Thirty Eight that polls try to avoid uncertainty.

“The incentives now favour offering a single number that looks similar to other polls instead of really trying to report on the many possible campaign elements that could affect the outcome,” Yost said. “Certainty is rewarded, it seems.”

In Australia, polling companies could also be trying to play it safe.

To achieve this, one of the ways polling companies adjust their numbers is through a process called smoothing. As Sheppard explains:

“Effectively, [smoothing] means that each time new Newspoll numbers are reported, they are adjusted based on previous Newspoll surveys. As a result, Newspoll numbers tend not to bounce around much anymore. Ipsos doesn’t seem to be doing that; they are letting their numbers bounce around considerably. It’s a much riskier strategy for a pollster, but one that may well pay off,”

So that could help explain why Newspoll and Ipsos have got such different numbers in their recent polls. Ipsos may have correctly recorded a spike in Labor support, but in Newspoll’s numbers that effect could be smothered by their smoothing method.

Do Polls Even Matter Much?

Erm. Not really.

“They matter as much as they provide a snapshot of opinion at any given time,” Sheppard said. “To the extent that they tell us how people will feel on election day, we should absolutely ignore them.”

One of the concepts the media gets behind is the idea of political momentum: that the real test of a party is whether they can convert their political wins into long-term support.

And after these recent polls, media today are really hamming that up.

Sheppard thinks the concept is complete bogus.

“There is absolutely no evidence for momentum in politics,” she said. “I am of the opinion that mistakes can accrue over time, but that good or popular decisions are pretty quickly forgotten, and voters move on.”

So what should the government take away from these recent polls, then?

Basically, Sheppard says, the news should make Turnbull feel pretty good.

“I suspect the government did not expect a particular ‘budget bounce’ in these polls; budgets haven’t been particularly popular since the revenue-heavy days of the early 2000s.”

In Sunday’s Newspoll, 41 percent of voters rated the budget as “good”, and 26 percent thought it was “bad”.

Sheppard concluded:

“But I would think that Turnbull is feeling quietly happy that things aren’t going south, at least.”