On Russell Brand, And Opinions On The Internet

Earlier this week, we published a contentious opinion piece on why Russell Brand's televised call for a revolution was wrong. Here is a response to the response.

I’m a white male in a hetero-normative relationship. I went to a private school, and now I live in Melbourne’s inner city. I don’t have a day job, but I do ride a bike. I hold socially progressive views, and carry a sense that fiscal policy really shouldn’t be ideological, but inevitably is. I also drink coffee.

Weird way to start an article? Sure, but now you know whether I’m your sort of person or not, and whether to read this article or skip to the comments and launch an ad-hominem diatribe against me and everything I represent.

My editor and I discussed the remarkable reaction to Daniel Katz’s op-ed, ’Why Russell Brand is Wrong About (Almost) Everything’, which was published on Monday this week. Coming as it did from a perspective that jarred with the liberal-minded sensibility of the site and its readers, it generated a predictably strong, but disappointingly spiteful, response. I toyed with writing a response to the piece, but in the end we agreed that both the article and the response were representative of something a little bigger.

That something is the state of social and political discourse in 2013, and the breathtaking lack of civility that has come to seem normal among adults. I have no idea how grown-ups used to talk about issues of substance before the internet came along, but I know how those in my sphere talk about it now. They talk in all caps, they mostly preach to the choir, and they demonise The Other, making assumptions about the character of anyone that expresses a differing view. We have derisive short-hand terms for them, as they do for us, and the assumptions on which our worldview is founded go untested because we know we’re right.

On ‘Why Russell Brand Is Wrong About (Almost) Everything’

The spiteful responses that Katz’s op-ed attracted could be roughly split into two: those motivated by ideological opposition, and those who were bothered by a few of its insensitive, factually incorrect and potentially harmful assertions.

My own objections to the article were threefold, and in the interest of providing a counter-balance, are detailed below:

“Pick any Middle Eastern or African country and I can tell you two things about it: first, the leaders are neither inspiring nor representative, but they are very corrupt. Second, each of their citizens cares about politics.”

1) Authority. Speak for yourself, and speak of what you know. Do not speak for a diverse region of over 200 million people, or a continent of over a billion people.

“Now, even someone living in poverty can travel by bus, listen to music by stereo, and order food cooked by someone else (sure it’s Pizza Hut and not a Michelin Star restaurant, but the point stands).”

2) Sensitivity. Do not tell the poor that capitalism is working for them, and that they should be grateful for what they have. Don’t call them ‘the poor’, either. Poverty is about powerlessness, not about whether you can afford to eat at Pizza Hut.

“By American standards, someone is ‘impoverished’ when they live on $30 per day. In developing countries, the poverty rate is $1.25 per day. A billion people live under that line. Not one of them lives in America, Australia, or the UK. In countries like ours, the poorest can earn several times that by begging, meaning that they are several times better fed, clothed and housed than people living in poverty in India or China — and yes, that includes people we call homeless.”

3) Selectivity. Do not assert that capitalism is actually fine because the impoverished are getting richer, or because their poverty is only relative. The same capitalist mechanisms — comparative advantage, economies of scale — that created the ‘relatively impoverished’ US underclass also created the absolutely impoverished third world. It’s okay to be way down with capitalism (it has plenty of positive aspects, and it’s the only economic system that the majority of Australians have ever lived within), but a refusal to acknowledge any of its failings, while suggesting that every socialist state, past and present, is doomed to suffer the fate of the Soviet Union, is dishonest.

Despite the strength of my objections, they were not personal. I didn’t want to beat Daniel so hard with my internet fists of rage that, rather than listening to me, he hardened not only his personal beliefs but his beliefs about people like me. I wanted him to hear me out, in the hope I would at the very least prompt him to reconsider the way he presents his ideas, if not the ideas themselves.

Daniel responded. He acknowledged my point, I acknowledged his. If I were ever to meet him, I’d have a beer with him. Or a coffee. I’d try to put him right on a few matters. Likewise, I’m sure he’d be keen to remove the scales from my eyes as well.

On Confirmation Bias

I would do this because I think it’s incredibly important to have one’s beliefs tested. ‘Confirmation bias’ is our tendency to seek out information that reinforces a pre-existing view, while ignoring or distrusting information that challenges it. It’s a pretty useful psychological trait — given how many decisions we have to make without possession of the full suite of relevant facts (train or bus? Steak or parma?), it prevents us from being haunted by the contingency of the world and the sheer inadequacy of our knowledge.

Confirmation bias, though, is poisonous to political discussion. It’s what leads us to dehumanise our opponents, casting aspersions about the content of their character rather than acknowledge weaknesses in our own arguments. It is, in part, why Daniel was subject to comments such as the below:

“This particular article is pretty much utter bullshit…You guys have our permission to fire Daniel Katz or the editor. I know who Russel Brand is. And I guess no one knows who Daniel Katz is.”

“Awful article with terrible arguments, evidence and examples.”

“This author is nearly as much of a pompous arse as Paxman.”

It’s not the worst that the internet has to offer, but it’s the sort of stuff that precludes open discussion. Confirmation bias puts us in a defensive state, in which we routinely fail to consider that others’ differing experiences might have led to a completely different understanding of the world, because their world is completely different.

In the internet age, of course, the mitigating factor of social etiquette is gone, and we no longer have to look our interlocutor in the eye and acknowledge their ho-hum humanity. Instead, we can passive-aggressively unfriend our Facebook friends when they change their profile picture to ‘you are not my Prime Minister’, or turn commenters into human punchlines on parody twitter accounts.

This tendency has reduced the almost limitless scope of our online activities to time spent in ideological ghettoes, furiously agreeing, seeking the consolation of the like-minded. Meanwhile the middle ground — the admission of doubt, weakness, nuance — melts away like the polar ice caps which are definitely melting seriously how can you disagree with science fuck off back to the middle ages you premium douche.

“One Man’s Trash”: The Malleability Of Hard Facts

The asylum seeker/queue jumper/boat people/illegal immigrant discussion is a good example of what I’m talking about, because you can’t even mention the subject without betraying your stance on the issue – and once you’ve betrayed your stance, half of your audience stops listening and starts sharpening their internet-quills. I won’t pretend to be impartial, but I will try to lean on facts where possible.

There are statistics that prove the effectiveness of John Howard and Phillip Ruddock’s ‘Pacific Solution’. In 2002, the year that followed the Tampa Crisis and the implementation of that incredibly divisive policy, the number of asylum seekers arriving by boat dropped from 5516 to one.

If you are pro-Howard, you would consider the argument won at this point. If you are anti-Howard, you might point at the considerable human cost of the policy, of the deaths at sea that those statistics fail to shed any light on, of allegedly degrading conditions in Nauru, and the alleged prevalence of sexual assault on Christmas Island. If you were a cynic, you might point out that a relatively small-scale human rights issue has been politicised and turned into a national security issue, in order to create political capital out of fear. If you were an idiot, you’d say fuck off, we’re full.

Excepting the idiot’s perspective, these are all reasonable positions to take on an incredibly complex issue. Both sides can draw on statistics. (Pro-Howard? Here are the stats on arrivals by boat. Anti-Howard? The Age makes a credible claim of 1500 deaths at sea over the past 25 years.) Both sides can mount an appeal to compassion: compassion for those directly affected by Australian policy, or compassion for those seeking asylum through official channels, and for the future victims of the people smugglers that would prey on our weakness.

At Least 50 Shades. Possibly More.

Anything that’s worth a damn tends to come in shades of grey. There’s not really a right or a wrong boat arrivals policy, there’s just whatever compromise that allows you to sleep at night (incidentally, if you’re having a good night’s sleep, you’re almost certainly not directly affected by the policy, so be thankful for that). Problem is, human nature doesn’t really allow us to feel comfortable with that sort of compromise, and the wisdom of what is ultimately, at least in part, an arbitrary position.

What I’m saying here probably won’t be enough to convince anyone to abandon their beliefs, but hopefully it encourages someone, somewhere, to behave a little better towards someone that they disagree with. After all, a discussion is not something you can win. If you’ve made your point convincingly, but in a douche-y way, congratulations, you’ve lost.

If you’ve constructed an argument that you know is misleading because hey, your cause is just and the ends justify the means, congratulations: we’ve all lost.

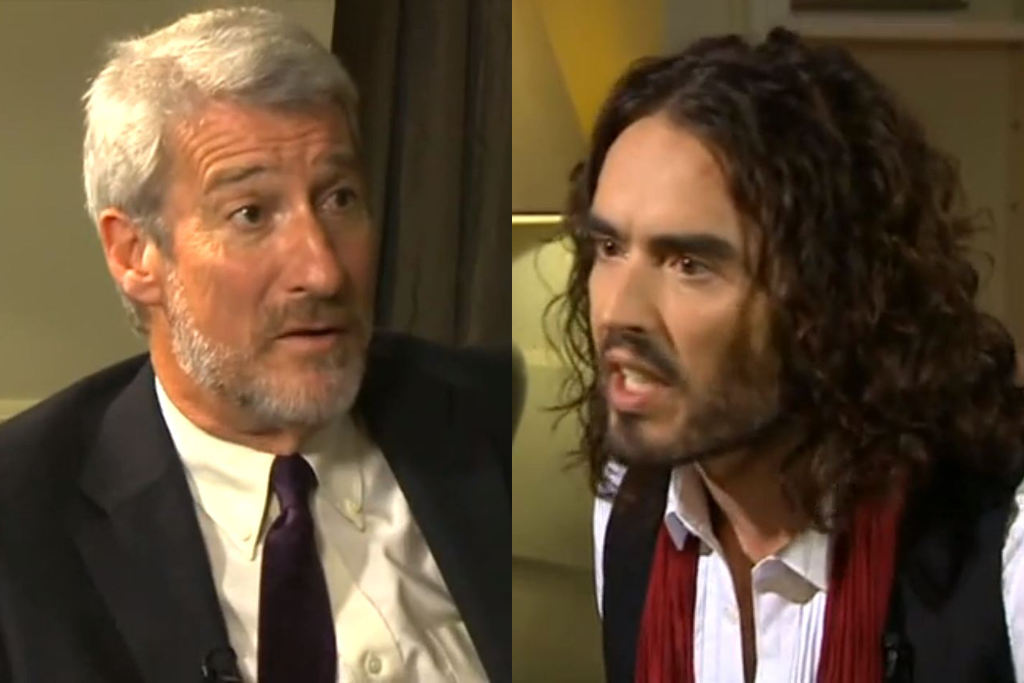

This applies to commenters, but it applies far more to writers/commentators/polemicists. We have a responsibility to use our platform responsibly, rather than scoring cheap points and playing to the gallery (something I’ve been guilty of myself: here’s me playing fast and incredibly loose with the life’s work of Richard Dawkins). Daniel had a right to point out that Brand’s advocacy of a socialist utopia is naïve and a little undercooked, but he had a responsibility to point out that Jeremy Paxman asked leading questions and put words in Brand’s mouth, too – not to mention a responsibility to get his facts straight. Brand, for his part, probably oughtn’t have outlined his utopian plan, and while he acknowledged that others were better qualified to discuss such matters, the fact remains that it was he who was heard by millions.

Absolute Power

And so to the bit where Russell Brand, Daniel and I are in resounding agreement (I think): the need to display vigilance toward those in power.

This is why I am worried when I see people strapping on an ideological suit of armour before they hit up a discussion thread. If you spend your time trying to ‘repeatedly own’ a fellow citizen who is probably not that different to you (middle class, educated, probably), then not enough time is being spent holding leaders – your leaders, their leaders, our leaders, all of them – to account. And by ‘holding to account’, I don’t mean, “I’m so ashamed that a ginger hag is running the country”, and, “OMG Tony Abbott’s such a fuckwit”: I mean engaging critically with their positions, their failings, their little deceits and compromises. Everyone’s entitled to an opinion, but if you’re reluctant to take this basic step, then yours is worth a little less.

We treat politics like sport, supporting our team and forgiving their mistakes, because it’s our team, it’s too late to switch, and we want to win. We neglect the fact that we are all on the same team, the subjugated*, and that when we accept ethical compromises – because of our fear of an other that we long ago stopped listening to and stopped trying to understand – we’ve stopped fearing the leaders of Our Team. We’ve been espousing their virtues and excusing their flaws for so long that we’ve forgotten that power is inherently fearsome, regardless of who holds it.

*I use this term not in the radical sense, but in the sense of a group having control exerted over them by another group. In this case, it’s the wider population having control exerted over them by the political elite. You might argue that in a democracy, power ultimately resides in the collective will of the people, and that would be a valid point.

–

Edward Sharp-Paul is a freelance writer and drink-pourer from Melbourne, who has written for FasterLouder, Mess+Noise, Beat and The Brag. Follow him on Twitter @e_sharppaul.