No Easy Answers: On Naming Names And Responsible Reportage

Local press wouldn't name the Australian entertainer arrested alongside Jimmy Savile - but it's been all over Twitter. Do traditional journalistic codes still apply in a new media landscape?

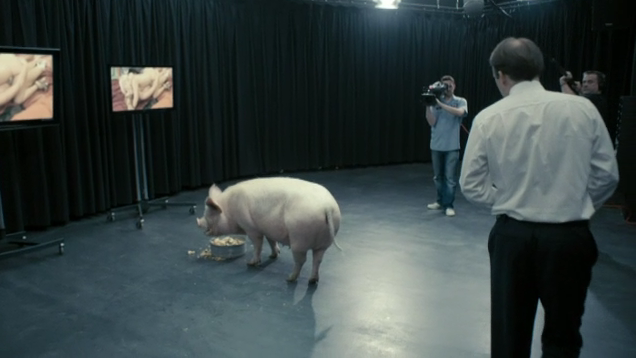

In the opening episode of the first season of Black Mirror — the terrific new-ish television miniseries-of-sorts from satirical pessimist and polymath Charlie Brooker — the character of the British Prime Minister is informed that he must have sex with a big fat adult pig on live television if he wants to prevent the beloved Kate Middleton-esque royal princess from being executed. Video of the bound-to-a-chair princess with accompanying ransom details are posted on YouTube in the pre-dawn hours; tens of thousands of people watch and replay and re-upload the video in just nine minutes before the British government manages to have it taken down. Because that’s how our internet — and thus our news cycle — now works: blindingly and unthinkingly fast.

This make-believe TV show feels disquietingly true: watching the episode play out, watching the familiar tautly-suited personages of this fictional government beetle into action, doing their best to minimise news of the situation spreading, there is no one point at which the scenario steps into the unreal. Maybe because we have come to view much of what happens in the world we live in, much of the technology we use and the science we accept and the news we devour, as somewhat grotesque and unbelievable. We watch this government put up a fight; they battle hard, and it’s a losing battle — no, it’s a lost battle, a battle forfeited many years ago, when users of the internet suddenly discovered themselves as disproportionately influential.

Since that moment, central tenets of journalism, including privacy, authority, integrity and quality, have been slowly but uninterruptedly abrading, like a wedge of parmesan cheese on a sharp steel grater. We’ve seen it happen abroad, in the reporting of politics and crime and celebrity news, and we’re seeing it happen in Australia, as the few excellent journalists, the ones with respectable codes of ethics, begin to look very lonely as they stand above the teeming masses.

In this above-described episode of Black Mirror — it’s titled ‘The National Anthem’ — the UK news networks agree not to show the video of the princess with its extraordinary ransom demands, or even report on the situation at all, because of what seems to be a mixture of both duress (the government uses every short-notice legal method they can grab at) and goodwill (out of twin traditional respects for the monarchy and government). There are realistic newsroom fights between journalists and editors as to whether the networks should be reporting this gigantic news item or not, before the decision is taken from their hands when overseas networks jump all over the story, making the local broadcasters look foolish.

Throughout the 44 minute episode until the (nail-biting) end — and even beyond — the pervasiveness of ‘new media’, and the unashamed need of the public for every dirty detail about every grubby news item, not only exacerbates the kidnapped princess/potential pig-fucking Prime Minister’s situation, but is revealed as perhaps the very reason this not-at-all-implausible scenario even occurred in the first place. The large media outlets, with their obligations to report responsibly, become almost passive observers, as individuals loom as the largest agents in the world (the real world) that is the 24-second news cycle.

The Wobbling Board Of Veracity: The Jimmy Savile Case

Earlier this month, a famous 82-year-old Australian entertainer was arrested on suspicion of sexual offences related to the Jimmy Savile case unfolding in the UK. “Is this commendable restraint or the media shamefully gagging itself?” asked Fairfax journalist Nick Miller, in an article in which he would not name the person. [UPDATE: Rolf Harris was named by the Sydney Morning Herald on April 19]

Because the news organisations were unable to confirm the identity of the man through official sources, his name had been largely suppressed, even though Twitter and every single other online forum had been bandying it around. This feels pretty ridiculous, but at the same time, surely it’s important that journalists still adhere to a code? A hundred (or thousand, or million) tweeters does not a fact make.

Columnist and commentator Martin McKenzie-Murray tells me that this particular case had less to do with the law. “There was no court injunction against reporting the suspect’s name that I know of, and more a sense of caution arising from the false — and quite sickening — accusations of child abuse.”

“There are many other considerations here, I think, suppressing the media’s inclination to name the person (such as the Leveson inquiry’s belief that the names of celebrity suspects are not in the public interest), but they tend away from the law,” he continues. “On another matter, allegations of pederasty or paedophilia are extraordinarily serious, and I can’t help but feel that allegations — ones that could later be proved to be false — will long haunt the person accused. The court of public opinion is pungently excited when it comes to child abuse — the allegations in themselves are so dastardly. But the corollary is the risk of seriously besmirching reputations. Whispers of child abuse can linger a long time.

“That said, if there’s a court injunction then there’s a court injunction. There’s no getting around that. In this case there’s not, so we have to look at the media climate in Britain and what that tells us about the inhibition.”

Not unexpectedly, journalist and news editor Ben Cubby — necessarily more of a steward to the daily news cycle — is a bit more pragmatic when it comes to the reality of publishing details:

“Reporting names and facts is obviously stock-in-trade. As long as you abide by the code of ethics, give people a fair right of reply, and keep an eye on defamation or other legal concerns, you should be fine in any medium. In general terms, deciding not to reveal relevant names or facts equates to hiding them from the reader, so there had better be a good reason for it.

“If a story can’t meet the minimum journalistic standards sufficient for publication, I’d argue that it’s probably not a story worth being frustrated about. It’s obviously quite common for a story to be ‘broken’ on Twitter, then reported later on in a newspaper or TV news bulletin, but the opposite also applies. The more traditional mediums are useful for announcing new information, joining the dots, and more nuanced analysis. They also tend to reach a wider audience. So these mediums can compliment each other.”

Fair Suck Of The Source Bottle, Mate

Radio broadcaster Derryn Hinch has repeatedly come afoul of the law with regard to revealing names without official confirmation, most recently concerning the Jill Meagher case — and he’s served prison time for his acts. Other Australian shock jocks — and also sometimes less unpleasant journalists — have faced court action for naming names and pointing fingers: Alan Jones has been found in contempt of court not just once (in August 1992), but twice (also in 2007); John Laws is a similar kind of muppet.

But more often than not, journalists abide by the (blurry) rules, which makes for news that is more morally upright, and also more boring. It seems that every year there are umpteen stories about various sporting codes and/or their players, where print stories can take up page after page and TV reports can go on for minute after minute without ever naming the players or teams involved. It’s like listening to someone tell a story where they can’t remember who said or did what or when it happened, but man you should’ve been there. Still, the alternative to such jejune reportage as this is what? Creative, imaginative, ambiguous news? That’s called ‘fiction’, and it doesn’t belong.

At a time when journalists are now finding it wholly necessary to call for laws to protect sources, as they face court actions from people like Gina Rinehart, it is perhaps more important than ever for reporters to be able to divulge all the facts, and not be made irrelevant by news-breaking tweeters – as long as it’s down with conscientiousness. (This kind of attack on reporting isn’t only occurring in Australia: late last week we heard of a Fox News journalist who may soon be jailed for not revealing her sources.) Today’s journalistic climate is becoming more and more majorly screwed up (‘undergoing large overhauls’ is probably the slightly more accepted term); decent hacks can be fired for calling bullshit on the substandard practice of their employers, and drones (or “J-bots”. J-bots!) are taking the place of on-the-spot reporting.

Being First, Or Being Right?

McKenzie-Murray knows well the current skirmishes that occur between the responsibility to give the public as much information as possible as quickly as possible, and the duty to report only what is accurate and fair: “There’s a serious tension between being first and being right,” he says. “Competition between networks inclines towards being first, where there’s a preference to break the story rather than providing substantive analysis. My personal opinion is that TV and radio stations are more bedevilled by this vanity than newspapers, just because of the nature of the medium. That said, with newspapers moving online and towards live blogs, etc., newspapers are increasingly pegging their credibility to immediacy too.

“Ideally, journalists are not sacrificing quality and principles of fairness and legality simply to serve up a name of a suspect,” McKenzie-Murray continues. “Journalists must contextualise, corroborate, and check against principles. If you’re simply just trying to get out first and regurgitate as much information as possible for your readers, you’re probably not doing that. Information is useless if it’s not accurate. There needs to be a filtering of the raw information the journo is getting.”

Cubby agrees: “I suppose the tension between speed and accuracy is present whenever you are writing to a deadline, and social media can serve to intensify that kind of pressure. Journalist A.J. Liebling coined the catchphrase, ‘I can write better than anybody who can write faster, and I can write faster than anybody who can write better.’ That summarises the intent.

“Obviously mistakes happen from time to time, in the rush to get stories out first – I’ve made a few. If there is a situation where you would miss being first in order to be right a little later on, most people would prefer the latter. … Ideally, you would be able to do both.”

Level Up

Consuming much of today’s news is almost like watching a video game: it’s as though some journalists seem to be mashing the A and B buttons and maniacally twirling their joysticks in an attempt to ‘win’ at reporting. But have you ever watched other people play a video game? It gets tiresome very quickly.

So what now? Do we try and re-define what ‘responsible reporting’ means, in this dawning era of journalism? Do we expect our long-form and diligent journalists to jump on and ride the breaking news train? Perhaps in-depth reporting is soon to be extinct anyway, what with annoying 17-year-olds making millions and millions selling apps that violently condense news stories. Are you even reading this piece anymore? What’s happening on Twitter right now, anyway?

—

Sam Cooney is the editor and publisher of Melbourne-based literary journal The Lifted Brow. His fiction, essays and journalism have been published in literary journals, magazines, anthologies and websites in Australia and overseas.