“I Have No Doubt About Robert Durst’s Guilt”: ‘The Jinx’ Creators Talk Truth And Bias On Screen

"I think it would feel a lot better if we weren’t going to court."

Of course we all know how it ends by now. We’ve seen the moment when Robert Durst, speaking into a microphone that he’s forgotten is still recording, appears to confess to three murders. “What the hell did I do?” he asks himself in a half-slurred address. “Killed them all, of course.”

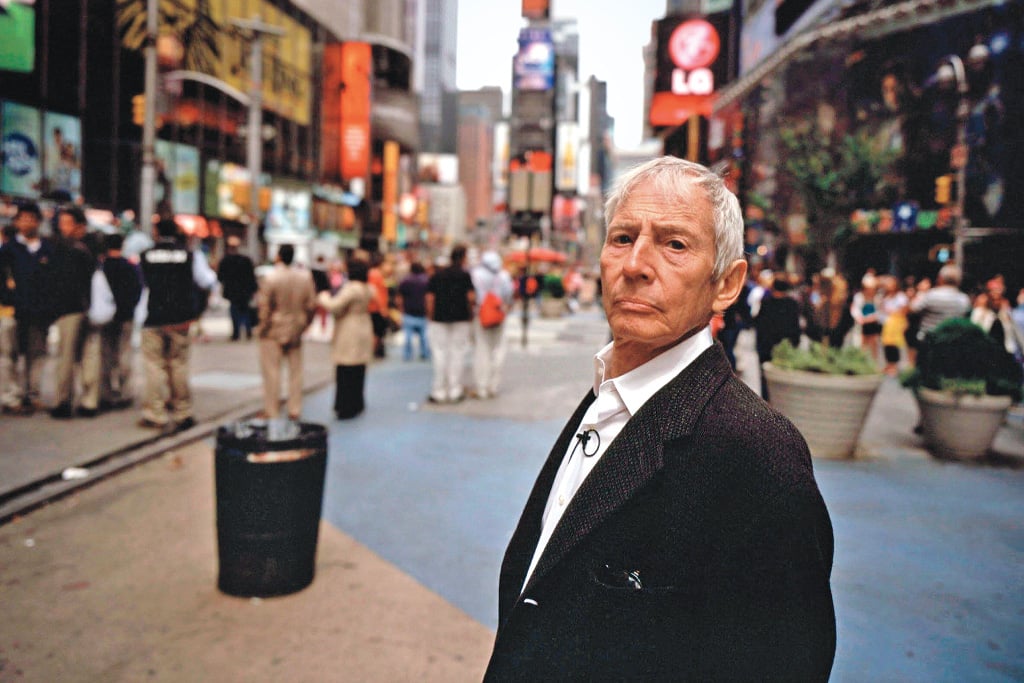

Durst was wearing a microphone because he’d been speaking to Andrew Jarecki, the director behind last year’s HBO docuseries The Jinx. It was the first time Durst had agreed to be interviewed about the events surrounding his wife’s disappearance in 1982, his close friend Susan Berman’s death by gunshot in 2000, and his neighbour’s dismemberment in 2001. Plainly, it did not go well.

–

Getting To The Truth

The other filmmakers behind The Jinx, Marc Smerling and Zachary Stuart-Pontier, will be keynote speakers tonight at the Australian International Documentary Conference, themed around ‘True Stories’. It’s appropriate considering that, in one moment, their story may have finally discovered the truth behind Robert Durst; something police and other filmmakers had been trying to do for almost 35 years.

“Andrew had the great reaction: ‘it can’t be this simple’” Marc says. “It’s just so simple, you’re like ‘this can’t be it’. We’ve worked so long and so hard to try to get to the bottom of these three murders. It just felt extraordinarily unreal”.

“It seemed like a long shot, honestly, when we first started [the project],” Zac adds. “All these cases had gone for 30 years completely unsolved. I thought that we’d get to the end and you’d have people who would think one thing, and people who would think the other thing, and we’d capture the disagreement and sort of present both sides so the audience can decide for themselves. But obviously that all changed.”

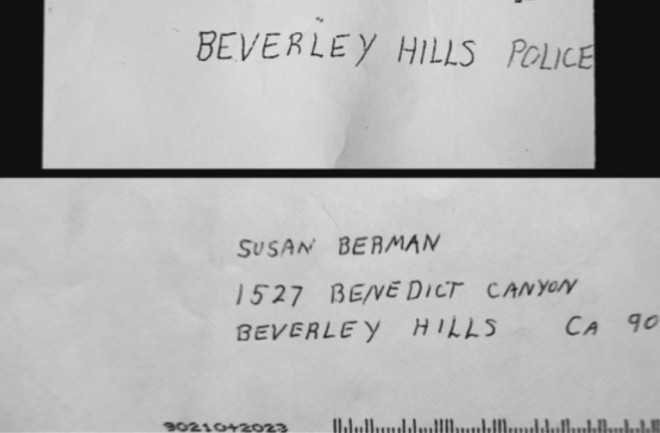

Of course, so much of this was by chance. What sends Durst into his burping, microphone-forgetting panic is the moment that Jarecki confronts him with a letter Durst had written to his long-time friend Susan Berman. The envelope bears her address “1527 Benedict Canyon, ‘Beverley’ Hills”, and the handwriting and spelling mistake in ‘Beverley’ appear to match a note sent to Beverly Hills Police alerting them that Susan Berman’s body was on the premises. If Durst had written both notes, he knew about the body. And if Durst knew about the body, it means he lied.

But the filmmakers didn’t have this note when they started filming. In fact, vast sections of The Jinx were filmed when the producers didn’t know how their mission would end. I ask if, without this piece of evidence, they ever had moments where they personally wavered over Durst’s guilt.

“Me, no. I have to be honest,” Marc replies. “I don’t know very many people who are close to one person who was murdered. Let alone three people who were murdered. And I had done a lot of research and talked to the NYPD about the cases, and there are a lot of unanswered and conflicting facts and questions. I thought, it doesn’t sound good for Bob. I think Andrew was on the other side; trying to figure out whether this was another case of misguided investigations. It was a misguided investigation to begin with, but I felt that Bob had a deep hole to crawl out of.”

“I think the idea was always that we would want the audience to have some experience of being on the fence, and going back and forth,” Zac says. “So in episode one we set him up as a body-chopper, a monster. He’s coming down the hallway and he’s staring right at the camera and it’s very intimidating, so the question is ‘who is this monster’? But then in episode two, almost immediately, the theory is to resurrect him. We hear about him as a child, he speaks a lot more eloquently than we expect, he tells a heartbreaking story and you’re kind of like ‘oh okay this guy is a person’.

“There’s a power to that back and forth. He’s completely different to what you think he is. He’s funny, he’s a human being, he’s got real emotions, he’s got real history. Doesn’t mean he’s not a murderer, it just means you have to understand him more.”

–

Telling The Truth On Screen

This kind of emotional dimension is what sets The Jinx, and for that matter most documentaries, apart from other sorts of truth-hunting like criminal trials or police investigation. The filmmakers had to do more than assemble some facts: they had to make those facts tell a human story about the real person at the centre of this series of events.

“Obviously we’re not building a case,” Marc says. “We’re building a film. We’re building a story. We have to be much more sympathetic to the people in the story, whether they’re bad people or good people. We have to try to dig deeper into the emotional basis of what drives the story. If you’re building a legal case that’s not very important, you know, you need evidence and you need to gather your evidence in a way that you can present in court. But we’re not doing that, we’re trying to create a connection between the audience and the people who are on the screen, that’s the most important thing. And that’s what gives The Jinx its power. Finding the evidence that we did, that’s a great plot twist to the story, but only in the context of finding out who these people are and particularly who Robert Durst is.”

So how does it feel to be in some sense publicly vindicated? The team behind The Jinx are in a position most documentary-makers will never be in: the truthfulness of their work is quite literally on trial. In the same year The Jinx was released, L.A. prosecutors struck a deal to have Durst extradited from New Orleans and taken to L.A. where he is now facing a murder charge over Susan Berman’s death. The case is scheduled to be heard sometime before August this year. Does this feel like vindication?

“I think it would feel a lot better if we weren’t going to court,” Marc says. “It’s all going to re-open again in some way that I can’t predict. I think we did a good job. I think we tried really hard to balance the necessities of journalistic endeavours with the necessities of creating something for an audience. And any journalist, if they say they’re not writing or creating something for an audience, they’re not being honest. So we did recreations, and we did things that would make the show more delicious for an audience, and I think we did a great job also of finding and investigating three murders and finding evidence that proves Robert Durst’s guilt.

“I have no doubt about Robert Durst’s guilt anymore. And I think after watching it, a lot of people feel the same way. But it’s all going to be re-hashed in the courtroom, and we’ll see what happens.”

–

Smerling and Pontier are talking about all this tonight with Australian author Martin McKenzie-Murray at AIDC in Melbourne.

–

Eleanor Gordon Smith teaches ethics and philosophy at the University of Sydney.