How Does Netflix’s ‘A Series Of Unfortunate Events’ Stack Up Against The Books And Film?

In a world of unnecessary reboots, this one might be Most Pleasantly Surprising.

On a scale from ambivalent to adverse — a word which here means against or in opposition — my feelings on reboots of any kind generally tend toward the latter. However, in some cases, such as when improvements need to be made on an insubstantial original, I can make an exception. Netflix’s A Series of Unfortunate Events, based on the excellent middle-grade novels by Lemony Snicket (alter ego of author Daniel Handler), is one such exception.

In 2004 the books, about three rich and recently orphaned children with supremely bad luck, were adapted into a film starring Emily Browning as one of the beleaguered Baudelaire orphans (the series’ heroes), and an overindulgent Jim Carrey as villainous antagonist Count Olaf. That film never quite captured the quirk, cleverness and refreshing irreverence of Handler’s exceedingly popular series.

Netflix’s new series, which stars triple-threat Broadway hero Neil Patrick Harris as Olaf, Patrick Warburton as Lemony Snicket, and three talented unknown actors as the ruthlessly unfortunate Baudelaires, does more than just nail the tone — it improves on it. In a world of unnecessary reboots, this Series of Unfortunate Events wins the gong for Most Improved and therefore Most Pleasantly Surprising.

Dear Reader…

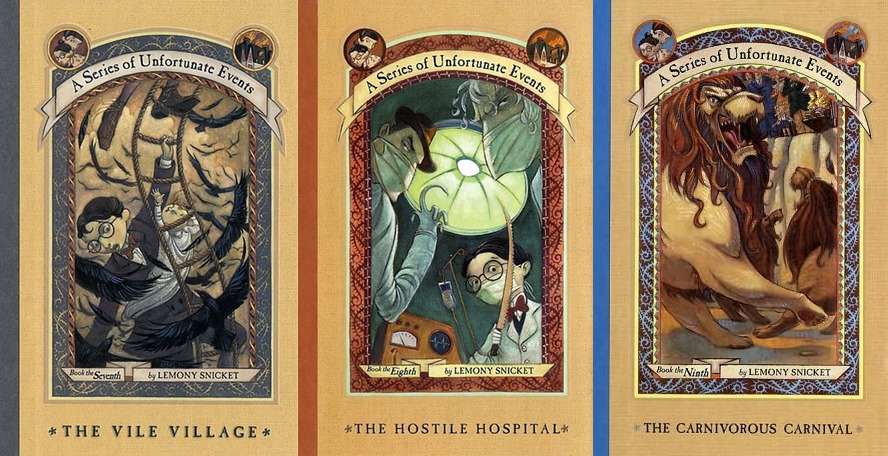

The Series of Unfortunate Events books were released in 1999, with Handler writing under the pseudonym Lemony Snicket: author/investigator/narrator/mysteriously omnipotent authority on the lives of the precocious Baudelaires. Snicket relays to us how, after discovering the terrible news that their parents have perished in a fire, the orphans are ferried from one truly bizarre guardian to another; each new circumstance piling on their worry and woe. They are pursued each time by Count Olaf, a bad actor of low intellect who seeks the Baudelaires’ sizeable fortune. In each book Olaf returns sporting a thin disguise and enacting a new plan to swindle the orphans out of their inheritance.

Designed for smartypants, the books are dark and clever with a smack of silliness; they follow the blueprint left by that master of murky children’s writing, Roald Dahl. Even now, nearly two decades after their release, they regularly fly off the shelves at bookshops. (They’re designed for children aged 9-12 but read by many on either side of that narrow age range.)

Now you, Junkee Reader, probably remember the series well. Like me, you probably devoured them as a tween (and perhaps also as a teen) when they were first released. Perhaps you, like me, were interested when you saw that Neil Patrick Harris would take on the role of Count Olaf and revive a childhood favourite of yours. How much will Harris sing? You wondered, of course. Will he be as grating as Jim Carrey was in the dismal 2004 film? You worried, naturally. But, no doubt, your interest was piqued.

And so Netflix’s reboot of the series, was aimed at both the nostalgic OG readers and the enthusiastic young readers enjoying the books now. It’s a shrewd but risky venture. Every bookish viewer from 9-year-old children to 30-year-old nostalgia-loving millennials is quite the demographic to straddle successfully, and the series sometimes struggles to strike the right balance regarding who, exactly, it’s speaking to.

The Netflix Bloat Vs. Some Good Wit

There is a long-acknowledged problem with shows from Netflix: however much we enjoy them, however much critics laud them, there’s always something about each “original series” produced inside the streaming giant’s hallowed halls that’s NQR. For most shows it’s a feeling that creators have been given rather too much freedom to produce however they please. This usually translates to too-long episodes, too-flabby storylines and too-self congratulatory meta-referencing. (In A Series of Unfortunate Events, for example, there is a rather tiresome running joke about the benefits of streaming long-form television that gets evermore up its own arse with each repetition.)

Critics and viewers of Netflix shows often comment on a series’ explosive beginning, drudgery in the middle and menial (if generally satisfying) ending. So it is in A Series of Unfortunate Events, where the first few episodes delight and entertain, while the middle few drag and test the viewer’s patience. Handler (who adapted his own books to screen for this series) and co., to their detriment, have split each book into two episodes (most of which are around 45-55 minutes long, with one stretching to a bloated, gruelling 64 minutes). This is a lot of time to translate a narrative built for tweens, and it shows. The best advice I can give to those diving into this mostly delightful series is to treat it like it’s NOT a Netflix show. Handler’s work is not meant for the binge approach, and spreading out each story (in their two-episode instalments) will be much more enjoyable.

The length and flabbiness of the piece, tending towards tedium as you hit episodes five and six, is probably the most tiresome element of the whole series. Apart from that, Handler and co. have done a fine job transporting the story of the Baudelaires to the small screen. Much of this is to do with Warburton’s robust, wry performance as the deadpan Mr Snicket. He pops up periodically to deliver omnipotent side-notes, titbits and comprehension lessons, forever wearing the stern brow and thin mouth of a pessimist. I looked forward to every reappearance (especially when the piece began to drag somewhat).

Warburton is perhaps the best example of how Handler, director Barry Sonnenfeld et al have really pinned the tone: a knowing, naughty kind of wit. He is well-matched against Harris’s gleeful and nasty Olaf — a vast improvement on the antics of Carrey who, in 2004, looked as though he’d been left in a room with a camera rolling and told to simply “go nuts”.

Harris is more methodical and controlled and, as a result, his Olaf is more menacing and infinitely more enjoyable (even if he does fulfil the NPH quota of one song for every hour of screen time). At the very least, the series will no doubt garner an Emmy nomination for Harris’s energetic work, as well as for his team of hair and make-up magicians, who created a collection of brilliant and variously hideous Olaf disguises.

Also wonderful are the quirky supporting players: Joan Cusack delights as the kind (if oblivious) Justice Strauss; former Daily Show correspondent Aasif Mandvi is a comforting and robust presence as herpetologist Dr Montgomery Montgomery; and the wonderful K. Todd Freeman levels the show’s inconsistencies as the hapless and hopeless banker Mr Poe. The children, too, are appropriately muted and precocious as necessary (and probably the aspect of the series that will rankle you most if you’re revisiting as an adult). My favourite, without a doubt, is the baby Sunny. Never in my life have I been more in awe of the comedic talents of a subtitled, CGI-enhanced infant. (Truth be told, she gets the bulk of the funniest lines, so you have to watch carefully to catch them.)

The series is beautifully designed to resemble a kind of neo-gothic French cartoon. It looks wonderful and expensive — two things Netflix does very well with its mountains of dosh. My favourite set is the underground catacombs where Lemony Snicket and his fellow shadowy spies/allies wander. Part-train tunnel and part-underground sewer, they’re dark and mysterious and suit the style wonderfully.

This brings me to the other great innovation of the Netflix brood. The lingering story of a suspicious organisation (which it’s suspected is populated by the late Baudelaire parents, Snicket and perhaps even Olaf) makes an impression much earlier on in the Netflix series than in the books or the film. We find out more about the organisation, and the fate of Baudelaires’ seniors, and we’re given to understand that the mystery of the secret organisation (marked by an eye insignia) is vital to the story’s long-term trajectory. This is no doubt an adjustment made to keep the attention of adults, and it works a treat. When the repetitious misery of the Baudelaire story becomes a bit monotonous, the thread of the secret organisation returns (along with some exciting celeb cameos) to perk you up.

So, It’s Worth The Time?

Courting two disparate demographics (enthusiastic youngsters and jaded young adults) is no easy feat, and at times A Series of Unfortunate Events fails somewhat in this regard. Some jokes work only for the grown-ups, others for the kids, but precious few appeal to the broad band of viewers. However, it’s admirable how Netflix has attempted to bring the nostalgic oldies and the keen young’uns together to watch A Series of Unfortunate Events unfold.

In the theme song (sung, of course, by NPH), the wobbly refrain is “look away, look away” — a warning about the terminally unpleasant fate of the Baudelaire orphans, which awaits you if you choose to watch. Nevertheless, I would advise not to heed NPH’s warning.

–

A Series of Unfortunate Events is on Netflix now.

–

Matilda Dixon-Smith is a freelance writer, editor and theatre-maker, and a card-carrying feminist. She also tweets intermittently and with very little skill from @mdixonsmith.