‘Making A Murderer’ And The Presumption Of Innocence: How Much Should We Really Believe?

Something to think about before signing any petitions.

This post contains spoilers for Making a Murderer.

–

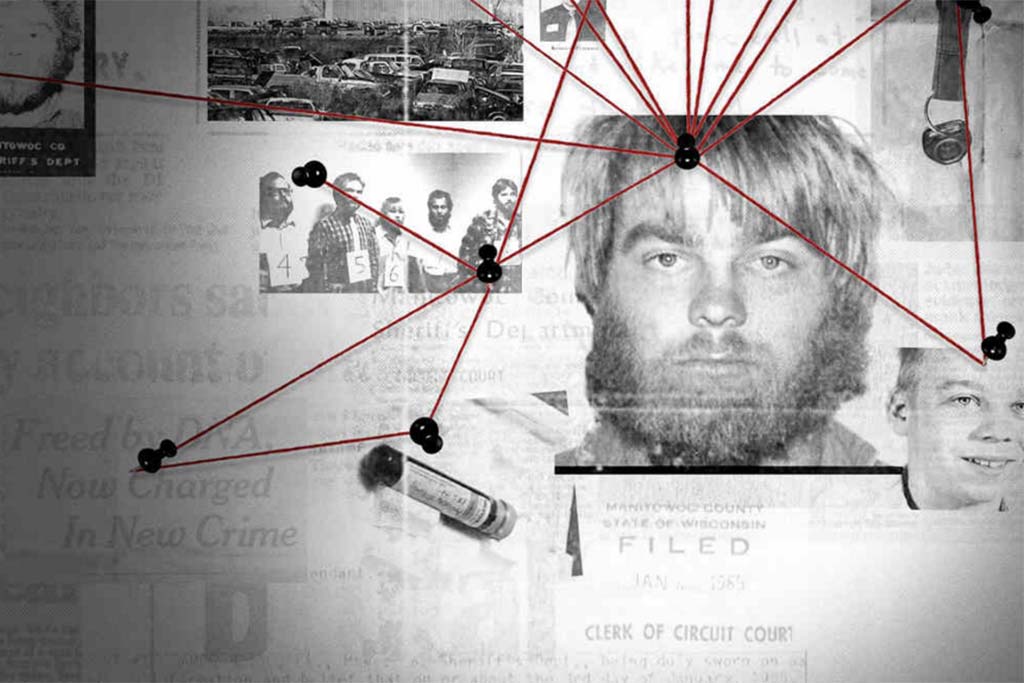

Since premiering on Netflix last month, Making a Murderer has attracted fervent debates across every branch of social media and solidified its place as the next true crime cultural sensation. It’s the new Serial. And, just like Sarah Koenig’s personal and deliberately structured examination of the guilt of Adnan Syed, it’s also undeniably manipulative. It gradually builds a fire of apparent injustice that encourages its viewers to boil over in outrage. It wants you to think Steven Avery is innocent.

For those who haven’t seen it, Steven Avery is the subject of first-time directors Moira Demos and Laura Ricciardi’s ten-part docudrama. When the show begins telling his story in late 2003, he’s just been released from an 18-year prison stint for a sexual assault he didn’t commit. With this, Making a Murderer — like any show built for streaming — hooks its audience with a compelling premise: Avery’s conviction was driven by alleged police corruption and, midway through his lawsuit against the Manitowoc County Sheriff’s Department he’s arrested for the murder of a young local photographer, Teresa Halbach.

Making a Murderer’s title implies that Avery was framed — either by police officers facing the lawsuit or someone with knowledge of it. And as such, the show follows Avery’s ordeal step by step, from his initial arrest to an intensely infuriating trial.

In presenting Avery as a victim from the outset, Making a Murderer glosses over his ‘youthful misdeeds’ — which include running a relative off the road while brandishing a firearm and reportedly accidentally incinerating a cat — by framing them as motivators for dishonest detectives looking to put away an outsider. As the case against Avery commences, we linger on the evidence that supports the defence’s argument. Some is convincing (the suggestion that Avery’s blood was planted in Teresa’s car is supported by a tampered vial of his blood in police possession) and others less so (the questions posed about the reliability of provided DNA evidence, for instance). Interviews are conducted only with friendly participants including Steven’s friends, family, and two defence attorneys who would later become the internet’s dorkiest sex symbols.

I'm going to get a locker in 2016 just to put this up: #MakingAMurderer pic.twitter.com/PES6xqQbAO

— Kristen Bell (@IMKristenBell) January 3, 2016

If Making a Murderer wanted to create sympathy for Steven Avery then it’s well and truly succeeded. The White House recently responded to an online petition signed by more than 410,000 people calling for Avery to be pardoned. Granted, the response was pretty terse considering Obama has no legal power to pardon those convicted by the State, as Avery was.

But why is it that we, the citizens of Netflix, consider ourselves such experts on the matter?

–

“Evil Incarnate”: The Other Side Of The Story

It’s not difficult to imagine what the show would like if it were done from the opposite perspective: a documentary on Halbach’s family.

We would learn about Teresa’s background and personality — which was omitted almost entirely from Making a Murderer — and we’d be shocked by both her sudden disappearance and the discovery of her blackened bones. We would hear about Avery and his dubious reputation (glossing over his false conviction), and feel sickened by his nephew Brendan Dassey’s subsequent confession of rape, murder and mutilation with his uncle (without mention of it being possibly coerced). We would breathe a sigh of relief when both Steven and Brendan are convicted of their crimes. Maybe it would be called Evil Incarnate: the phrase Len Kachinsky, Brendan’s defence attorney, once used to described Avery. Of course, this work would be just as manipulative as Making a Murderer, if not more so.

If there were filmmakers out there looking to take this approach, there’s plenty of evidence left out of Making a Murderer they could incorporate. Prosecutor Ken Kratz noted that key pieces of information in the State’s case like the presence of Avery’s sweat on the latch of Teresa’s car were omitted entirely. Though maybe you find it hard to give too much credence to Kratz after learning of his sexting scandal, which was cleverly included in Making a Murderer’s final episode as a kind of pre-emptive ad hominem.

But Kratz isn’t the only one speaking out. After the show’s release, a number of reporters claimed that Avery had a documented fixation on Halbach prior to her murder and that he’d recently purchased handcuffs and leg irons. Even when combined with the facts presented within the documentary itself, this information would threaten the public affirmation that Avery is innocent.

All that said, I’m not here to criticise Making a Murderer for its manipulations. While I would rebuff any claims of ‘impartiality’, there’s nothing wrong with a documentary acting as advocate — though Ricciardi refutes this, claiming her work is “very thorough and in, our opinion, very accurate and very fair”. The real issue is the unquestioning fervour with which the series’ considerable fandom has leapt upon the issue, poring over the State’s case for every possible flaw but failing to regard Making a Murderer’s biases with the same scrutiny.

–

The Rarity Of “Innocent Until Proven Guilty”

What Making a Murderer really does, by taking the side of the accused, is something all too rare in the justice system and mainstream media alike — it takes the presumption of innocence seriously. By aligning us solely with the suspect, rather than the prosecution, Demos and Ricciardi provide a corrective to a cultural erosion of the legal maxim “innocent until proven guilty”. That’s exemplified within the show itself, when Kratz addresses the media to provide the supposed grisly details of Brendan’s “confession” — thereby biasing any potential jury and turning the public against Avery. At one point this is even stated explicitly by Dean Strang, one of Avery’s defence attorneys.

“All due respect to counsel, the state is supposed to start every criminal trial swimming upstream,” he says during the trial. “And the strong current against which the state is supposed to be swimming is the presumption of innocence. That presumption of innocence has been eroded — if not eliminated — [in this case].”

The presumption of guilt rather than innocence pervades many elements of not only the story as it’s presented but also the wider world in which it’s based. The circumstances of Brendan Dassey’s confession, for instance, clarify that interrogators can regularly compel confessions out of unprepared and uneducated young people. And, though it’s possible Dassey’s statement is more damning than the snippets seen in Making a Murderer — the whole thing is available online if you have the stomach for it — it’s clear that confessions carry a perhaps unwarranted amount of weight for both jurors and the general public.

Making a Murderer is about the failing of our judicial system, whether or not Avery is innocent is actually secondary.

— Aya Cash (@maybeAyaCash) January 8, 2016

Whether or not Avery and Dassey are guilty, Making a Murderer proffers a disheartening portrait of a justice system absent of justice — one driven by police officers seeking convictions rather than the truth. Importantly, as Inverse noted, the series also “shows police corruption in such a way that white people can understand because it happens to a white person”.

Just as jurors should regard evidence presented in a court case with a critical eye, we should consider the various manipulations of Making a Murderer before drawing a conclusion about Avery and Dassey’s innocence or guilt. Hopefully the show encourages the courts to ask serious questions about the investigations and subsequent trials that convicted these two men. And hopefully it reminds us that “innocent until proven guilty” isn’t just an empty phrase.

–

Making a Murderer is streaming on Netflix now.

–

Dave Crewe is a Brisbane-based teacher and freelance film critic who spends way too much of his time watching movies. Read his stuff at ccpopculture or pester him at @dacrewe.