Liberace’s Life In The Closet Was Not A Tragedy. Discuss.

Behind The Candelabra is not ignorant of the wrenching personal sacrifices Liberace made through his life. But the film rightly chooses optimism instead.

As surnames go, Liberace is pretty snazzy. It rolls off the tongue. It has a vague air of aristocracy, and conjures images of a dreamy, faraway place peopled by good-looking foreigners. It’s not hard to imagine yourself sipping a fizzy drink called a Liberace as you sit on the pebbled beaches of Italy’s Amalfi Coast, soaking up the view and feeling pretty pleased with yourself.

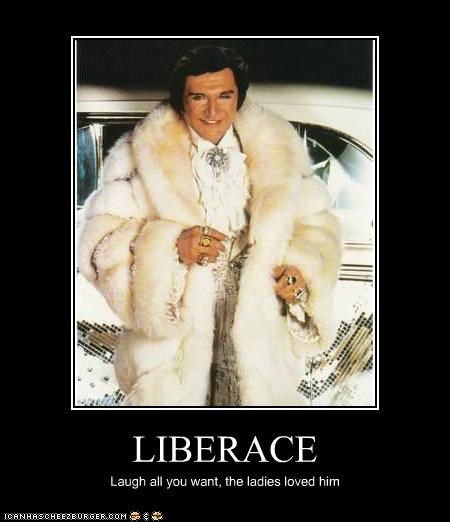

Liberace. Could it be a variation on liberate? Liberal? Or maybe libertine? That last one feels right: rifle through photographs of the most only memorable Liberace in pop-culture history, and you see someone who doesn’t appear to know restraint.

In fact — or at least according to my online research — the name ‘Liberace’ is derived from the Germanic name Alberecht, itself a mash-up of the terms Adal (noble) and Berht (bright and famous). Makes sense: at the height of his career, Liberace was a king among entertainers, brightly swaddled in furs, glitter and jewels. And he was stupidly famous: a constant presence on middle America’s TV sets, the adored matinee idol to millions of moony-eyed teen girls (and their mothers and grandmothers); a Vegas showman nonpareil.

Yet in the 25-plus years since his death from AIDS, Liberace has remained a strange, distant curiosity to most of us. For starters, his music hasn’t exactly aged well; it’s from another, more genteel era, a time when people still became pop icons with material like Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concert No. 1 or ‘Beer Barrel Polka‘. He was not exactly hip. In stark contrast to many of today’s most in-demand entertainers, irony was not (overtly, at least) part of his act, even if his entire existence now seems to embody the very idea.

He was a household name who sustained his popularity for decades, but Liberace never really let those fans know what was happening beyond the gates of his lavish homes, or under the 35-kilo furs he donned as he swooshed onstage for each new performance. This was 1987, remember, when people still worried HIV could be transmitted through touch, and when he died, the media circus so overwhelmed his army of yes men that their response only made his passing seem that much weirder and more shameful: post-haste, they pathetically tried to blame his demise on anemia caused by a watermelon diet.

A watermelon diet! Even in death, Liberace was ridiculous.

Life Inside Liberace’s (Seriously Huge, Gold-Plated, Lushly Carpeted) Closet:

We tend to presume, in our “post-gay” world — all same-sex weddings and Steve Grand and #itgetsbetter — that a life in the closet is no life at all. Visibility, we argue, is key; denial is potential death. But the story of Liberace — told with glorious wit and sensitivity in Steven Soderbergh’s new film Behind the Candelabra, out today — provides an intriguing counter-argument that muddies things up more than we might like.

The man was clearly terrified of being outed, orchestrating an elaborate, decades-long sham that mostly involved stepping out with publicist-approved female stars (Betty White was one of his beards, for crying out loud), magazine cover stories in which he shared ‘What I want in a woman…‘, and a willingness to sue anyone who questioned his masculinity. He usually won, gloating to the press that “I cried all the way to the bank!”

The son of an Italian immigrant and a nagging-but-lovable Polish mother, Liberace came of age during the Great Depression. These important facets of his upbringing colluded to make him a devout Catholic, conservative in his worldview, keeper of a diligent work ethic and a proud capitalist. Given the fact that he was already making a mint at a time when the politics of outing — much less the politics of even being out — didn’t exist, his terror at being unmasked is not remotely surprising.

And yet.

Watch a YouTube clip of Liberace for no more than a few seconds and you come to a simple conclusion: this guy was a flaming queen. He may have even been the 20th century’s first gay superstar, even if that’s not how he was perceived (and certainly not described).

I have a vinyl copy of his 1969 compilation Liberace’s Greatest Hits — a tongue-in-cheek gift from a house-sitter — and the liner notes are a hilarious exercise in coded language: “Liberace is the kind of storybook phenomenon that — if he weren’t so very real — wouldn’t be believed. With a glittering suit, an air of confidence that is a triumph of personal psychology, and a smile as wide and shiny as a piano keyboard, he has established himself as the first and only Personality Pianist.” In other words: you want sex, drugs and rock ‘n roll? Go buy a Doors album.

But offstage — for instance, behind that candelabra perched on his piano each time he played — the dude carried on in ways that Jim Morrison could only have dreamed. His signature catchphrase — often cooed to audiences at his shows — was, “Too much of a good thing is wonderful!” It’s clear he meant it: Liberace owned huge, opulent mansions with gorgeous pools, and gilded the ever-living fuck out of them. He employed a handsome coterie of fit, good-looking assistants and helpers, fawned over frou-frou dogs who followed him adoringly, and was never far from a bucket of vintage champagne, kept chilled on ice. He made an obscene amount of money and pampered himself (and others) accordingly. Gorgeous young men were willing to sleep with him, because he provided entrée to a world they’d never known; suddenly, sex with a balding, out-of-shape, middle-aged man wasn’t such a bad bargain when the reward was great drugs, free booze and some much-needed attention.

The more I learned about Liberace’s life, the easier it was for me to put aside my judgments and start appreciating the way he constructed his public persona: as one gigantic goof, a sleight-of-hand that literally let him have it both ways. In his 2012 book How to be Gay, academic David M. Halperin explains how “much of gay male culture delights in activities that — unlike gay sex, which is socially condemned as abnormal and unnatural — inspire widespread admiration on the part of straight society … insofar as they involve making the world beautiful. Just think of Liberace (who was also a house restorer on the side): only by constructing for himself an elaborately artificial identity as a classy and glamorous artist, as a purveyor of high musical culture, could he neutralize the contempt he otherwise would have incurred for being such a queen.”

Earlier this year, Liberace’s old friend Michael Thornton told The Telegraph “his intimate, familiar and sometimes gushing personal style conveyed reassurance to closet gays in an age of homophobia.”

What Behind The Candelabra Gets Very, Very Right:

Soderbergh understands both of those arguments, and embraces Liberace’s contradictions with typical intelligence, aided by a powerhouse cast led by Michael Douglas in the title role and the impossibly fit-at-40 Matt Damon as Scott Thorson, the pianist’s lover for a spell in the late ’70s and early ’80s. Soderbergh famously took Candelabra to US cable network HBO after he was told by every film studio in Hollywood that the movie was simply “too gay” (SPEAKING OF IRONY!) for theatrical distribution; lucky for us, Australia gets a proper cinematic roll-out.

It is worth seeing for a variety of reasons:

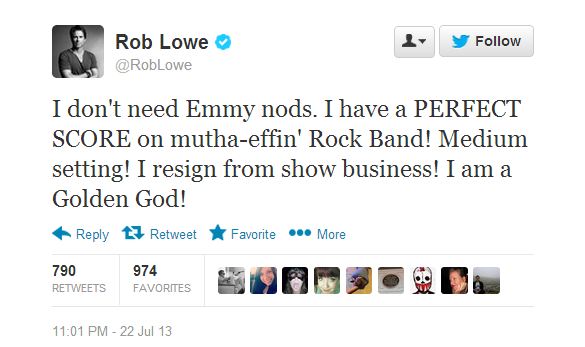

Candelabra is beautifully written, directed and acted. Last week, it received 15 deserved Primetime Emmy nominations, though I’m still aggro over the snub of Rob Lowe, so hilariously wrong as Thorson’s creepy-faced plastic surgeon/one-man drug dispensary. (Sidebar: read Lowe’s autobiography. It’s fantastic.)

That said, Rob Lowe seems to have gotten over it.

It’s a modestly budgeted, quality film, the kind that deserves as large an audience as it can pull in a market glutted with animated sequels, superhero movies and bloated flops. I promise you will not see anything like this in The Wolverine.

Or, for that matter, this:

Finally, it is often very, very funny (shout-out to Bruce Ramsay as Carlucci the houseboy!), and knowingly appreciates who Liberace once was, and what he ultimately became.

He Died Of AIDS, And Never Came Out. Isn’t That Kind Of Tragic?

Of course, what many of us myopically choose to see is a man who ultimately became a victim of what the folks over at ThinkProgress have called “the corrosive impact of the closet”. A fair argument? Sure. And Behind the Candelabra, to be clear, is keenly aware of what the closet did to Liberace (and everyone around him).

Thing is, the film’s brilliance stems from how intelligently it conveys that very message. Soderbergh never invites his audience to simply cluck at Liberace, or to feel pity for the double life he painstakingly crafted for fear of being found out. At no point does the movie make a value judgment of his retroactively icky decisions to hand-pick a young stallion and offer not only to adopt him (“I want to be your father, your lover, your brother, your best friend, your everything,” he explains to Scott), but also to literally have his charge’s face carved so that they more closely resemble each other.

Nobody denies Liberace must have housed deep, untold reserves of shame, guilt and pain. The closet is a brutal and unhealthy place, and staying there only calcifies those emotions. So I want to make it clear I’m not suggesting he was “right” or “better-off” in making sure those doors stayed bolted shut. But for Soderbergh and screenwriter Richard LaGravenese to have turned such a decision, or his swift and clandestine death from AIDS, into nothing but mere tragedy would have meant ignoring the fact that Liberace’s life was marked by admirably brazen indomitability, even if it was employed in the service of a secrecy now considered retrograde and dangerous.

Behind the Candelabra—much like Liberace—is not ignorant of the deep and wrenching personal sacrifices he made to get to (and stay at) the top. But also like Liberace, it chooses optimism, hums along on a heady wave of grandeur, and presents itself as a non-stop orgy of vanity and self-affirmation. That kind of behaviour ultimately cost the man his life, but… wow! What a life it was, the entirety of it too delicious not to be explored and reexamined through a (hopefully more enlightened) modern lens.

Behind the Candelabra is almost too much of a good thing, and that’s just wonderful.

–

Nicholas Fonseca was the acting deputy editor of Madison, and is a (sometime) master of film studies student at the University of Sydney. Prior to arriving in Sydney, he was based in New York City, where he worked for a decade as a writer and senior editor for Entertainment Weekly.