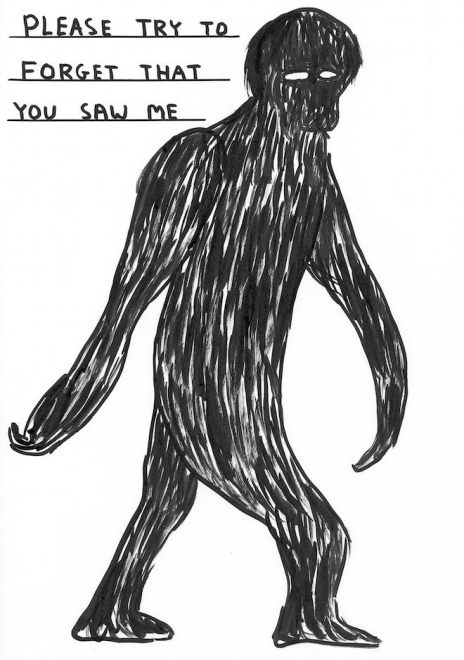

“It’s Only Civilised To Pee Into A Bucket”: An Interview With David Shrigley

Who is David Shrigley? David Shrigley isn’t sure.

David Shrigley looks around, leans forward and mock-whispers: “They’re a little bit conservative here.”

The Glasgow-based artist is talking about the National Gallery of Victoria, where he’s putting the final touches on David Shrigley: Life and Life Drawing, his first major survey in Australia.

“I’ve got these really good ideas,” he continues, “and they won’t let me do them because they say they’re ‘dangerous’ or whatever.”

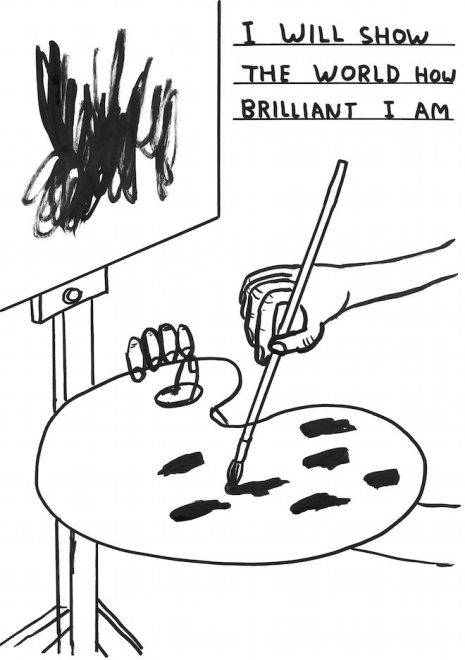

Untitled (I will show the world how brilliant I am), 2014, ink on paper, 29.7 x 42 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London. © David Shrigley

One of his really good ideas is for General Store, an installation-cum-shop he’s filling with the merchandise he’s built a global brand on: books, t-shirts, cards and miscellaneous knickknacks, all marked by his tell-tale dark humour and crudely drawn lines.

“I want to put a hot plate by the till and take all the change out of the till, put in on the hot plate so it’s really really hot — too hot to touch — and then if you want your change they get a metal spatula and flick it at you. I thought that was a really good idea. But it’s also a bit dangerous, so I’m not allowed to do it. Apparently.” He says he also floated the idea of keeping the coins slightly warm instead, just to make the whole experience of picking them up “feel really weird”. That wasn’t a go either.

But ideally, he wanted the hot plate. “I want the hot plate on full blast and then, if people don’t want their change, we flick it into a bucket of water — TSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSS — and when it cools down we donate it to charity. It’s a good idea, isn’t it? Well, it’s not the best idea — it’s not like the Rubik’s Cube or anything — but I think it’s a good idea.”

Good idea or not, it’s a funny idea. Dwell on it a bit and it’s actually a profound idea. To be fair to the NGV, it’s also a dangerous and maybe even slightly deranged idea. Like almost all of Shrigley’s ideas, it’s an idea that makes you laugh and makes you think, and might make you worry about the guy a little.

Untitled (I am very happy), 2014, ink on paper, 42 x 29.7 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London. © David Shrigley

He’s doing fine though. Just last year he landed a nomination for Britain’s big art award, the Turner Prize; come 2016 he’ll be completing a commission for Britain’s big temporary public sculpture spot, the Fourth plinth at Trafalgar Square. He’s such the art darling that Guardian art critic Adrian Searle had a scribble Shrigley drew on his stomach turned into a permanent tattoo. (“Imitation, tattoos and theft are the sincerest forms of flattery,” Shrigley quips.)

And a lot of his really good ideas did get through to his exhibition at the NGV. There’s the sign that reads “Don’t Write Poems”, for one. Or the two tons of brown clay, all of it rolled into one giant clay sausage that twists and curls upon itself. Or the robot sculpture of a human head with a pen stuck up its nose that’s programmed to zoom around making randomised geometric patterns on a large canvas on the floor. Best of all, there are countless examples of the drawings most know him for, filling walls from left to right, floor to ceiling.

The centrepiece of the show is Life Model, the sculpture he exhibited for his Turner Prize nomination. It’s a cartoonish, oddly proportioned kinetic sculpture of a man. Visitors are provided with paper, easel and art materials and are invited to draw him. Over the course of the exhibition, their interpretations will be pasted on the gallery walls. Every now and then, he blinks and pees into a bucket on the floor.

Life Model, 2012, installation view at Turner Prize, London Londonderry, 2013. Photo: Lucy Dawkins, Tate, London. © David Shrigley

Why does the guy pee into a bucket? The answer’s pretty simple. “You wouldn’t want to pee on the floor, would you? It’s only civilised to pee into a bucket or a similar receptacle.”

It wasn’t so much the pee as the Turner nomination that took a few by surprise last year. The funny nature of Shrigley’s work doesn’t gel with the expectations some have for the otherwise stuffy and self-serious art establishment. But Shrigley isn’t overly fussed about what people make of his work. “I’m not there and I don’t provide any commentary on it at the time that they’re looking at it. So whatever their understanding of the work is, is what it is, and I think one has to accept that.”

“I think people misunderstand who I am, but they don’t misunderstand the work because you can’t misunderstand the work.”

So if people misunderstand who David Shrigley is, then who exactly is David Shrigley? David Shrigley isn’t sure. From time to time, he’ll look at something he’s drawn and he’ll be surprised by it, to the point where “to some extent it seems like somebody else did it”. Sometimes it makes him laugh, sometimes it just makes him feel confused. He’s stopped reading what people write about him — “I’m sure they’re writing about somebody else,” he says.

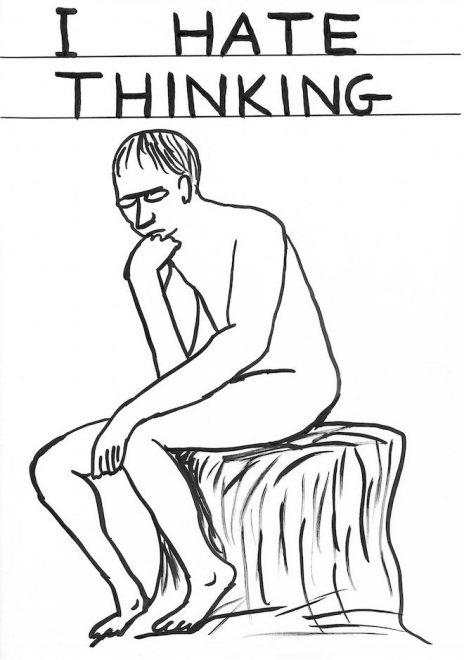

Here’s what he knows though. For starters, he isn’t an illustrator or a cartoonist. He’s an artist. He’s wanted to be one ever since he was 12, when he officially abandoned his plans to become a soccer player or an astronaut. “I went to art school,” he says. “I’m influenced by Marcel Duchamp, not by Gary Larson.”

Untitled, 2014, acrylic on paper, 75 x 56 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London. © David Shrigley

Shrigley graduated from the Glasgow School of Art in 1991, and is still learning. “I think you learn more when you’re younger, but I’m more aware now that I have a lot to learn and that it’s a journey, a process, and the art is just the residue of the process; the art’s the residue of that journey you make.” The humour in his work, it’s important to note, is another example of a residue of the process and the journey — it’s not the main point of his art. “If my work’s good, it’s not necessarily because it’s funny. It’s good in spite of it, maybe. If it is good.”

And just to nitpick a little further, the humour itself can be misconstrued. Sometimes slated as childlike or faux-naïve, Shrigley’s brand of comedy is more considered than some assume. “I think comedy is quite an adult thing. Children are entertained — it’s easy to make children laugh — but actual comedy is perhaps something that is more.

“When you’re a kid, I think you laugh at everything. When you’re an adult, comedy can be something that’s quite thoughtful as well, cerebral.”

Then again, if his comedy is serious, by the same token his seriousness isn’t too serious. The apparent existential despair in his tragicomic worldview is more of an existential not-so-chuffedness. “I think there’s something quite attractive in existential nihilism for the average 18-year-old boy thinking of going to art school.” He read Albert Camus as a teenager, but nowadays, “I wouldn’t say that I carry a copy of The Outsider around with me”.

He enjoys naps. He has a dedicated ‘napping station’ in his studio for power snoozes in the afternoon. Every now and then, his black miniature schnauzer Inka will join him for a doze. “Nothing’s more pleasurable than having half an hour of shut-eye with your canine companion,” he admits. There’s even what could be considered a nod to his nodding-off space in his exhibition at the NGV; a couple of quilts and a pillow have been placed in a corner, just in case a visitor feels like a quick lie-down.

He is rumoured to enjoy crap TV. “That is a lie,” he insists, when accused. “Probably put about by my wife. It is her that likes watching crap TV. It is me that, in the interest of having a harmonious relationship, watches crap TV at the same time. [When she’s away] I don’t watch any of the stuff that she watches: reality TV or talent shows, things like that. There’s a show about people baking cakes.”

But both he and his wife agree on one show: the BBC television program Gardener’s World. “I’m sure you have the equivalent here,” Shrigley says. “Where there’s a person. Who’s a gardener. And they talk about gardens. And they are in their garden. I really like that. But the odd thing is, I have no interest in gardening whatsoever. I [just] find it really comforting. Also, I don’t even have a garden, I live in an apartment.”

With David Shrigley the person sorted for the most part, that just leaves the matter of his art. Unfortunately, he can’t help you with that. “If my work’s about anything, it’s about everything,” he offers. “I’m very resistant to the idea that art’s like a crossword puzzle, where there’s a solution that you can get wrong.”

So anyone who’s up for entering his twisted world is on their own, really. Shrigley’s only advice: “Don’t touch anything. That’s pretty much it. Keep the dogs on a lead.”

–

David Shrigley: Life and Life Drawing will be on display at NGV International from 14 November 2014 to 1 March 2015. Open 10am-5pm, closed Tuesdays. Free entry.

–

Toby Fehily is assistant editor at Art Guide Australia and a freelance writer. His work has appeared in Smith Journal, ABC Radio National and VICE. He doesn’t really tweet at @tobyfehily.