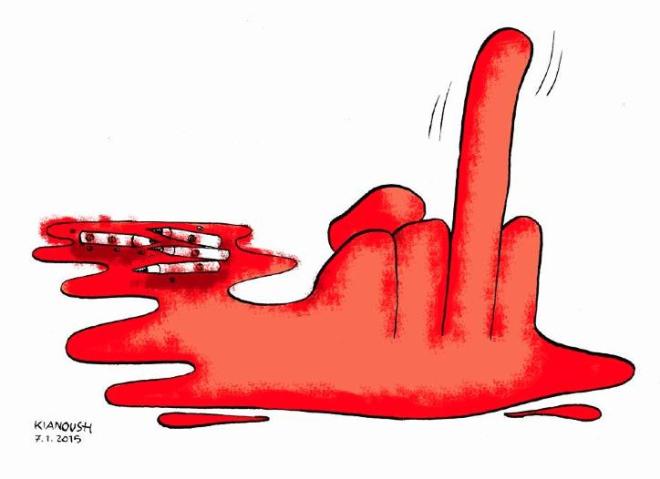

Islam, Satire And Life In France Post-Charlie Hebdo: An Interview With A Paris-Based Iranian Political Cartoonist

Meet Kianoush Ramezani.

Kianoush Ramezani is no stranger to the danger of artistic expression. The Iranian-born political cartoonist fled his home country in 2009, following Iran’s controversial elections and subsequent persecution of activists. He took refuge in Paris, seeking political asylum.

Following last week’s massacre in Paris at the Charlie Hebdo headquarters, Kianoush spoke about his reaction at the ground level – both as a political cartoonist and a citizen of Paris.

–

Junkee: Tell me about how you came to be living in Paris.

Kianoush Ramezani: I came to France in 2009, because I was in danger in my own country. I was the Iranian leader of the Cartoonist Rights Network International (CRN) — an international organisation based in the US that helps cartoonists when they find themselves in trouble. CRN was under surveillance and it was a huge risk. If you are representing an international organisation they [the government] can simply accuse you of being a spy, especially if you’re representing a organisation based in the US.

So after I saw some of my close friends arrested by the regime, I realised they could keep me there for many, many years and maybe also execute me. I went to the French embassy and I applied for a one month visa. I had to be very discreet. I couldn’t even say goodbye to my close friends, to my family. I came out of the country by airplane directly from Tehran to Paris.

How have you found Paris compared to living in Iran?

The first year it was hell. No language connection, no connection. I was seeing myself like a newborn child in a desert or in another world. After a while I connected with Reporters Without Borders [an organisation that helps exiled and persecuted journalists] and they helped me find my way.

Have you ever felt unsafe in Paris before this week?

Yeah, actually, in the first year. They [the Iranian government] were surveying us, they were watching us. But I just received some threats over the internet, and once they tried to hack my Gmail account. But not more. I don’t believe that an Iranian cartoonist living in Paris can be in serious danger from Iran.

How did you know Charb [editor-in-chief Stephane Charbonnier] and the other guys at Charlie Hebdo?

I first went to their magazine in 2010. They invited me to do an interview, and that’s how I got to know Charb and the other crazy people there. I told Charb I was worried about him – by my knowledge of the Islamist people, I knew he should really take the threat seriously. I told him that his life was in danger. But he told me that ‘You know what, I have no one, I have no children, I have nothing, whatever, I don’t care. Besides, I have my bodyguards all the time and don’t worry – I’m not living in Iran, we’re in France – it’s not like that.’

Even though you feared that they might be in danger, was the attack still shocking to you in its scale?

Of course, yes. Because the whole meaning of security and safety broke for me in that day. But then I realised that it was so predictable. And I believed that they also knew that it might happen. The security system of France that was supporting him [after the 2011 firebomb attack on the Charlie Hebdo offices] – maybe they forgot the seriousness after two or three years. Forgot that the Islamists never forgive and never forget. Because they’d decided to kill Charb in 2011.

Do you have any fear that in six or 12 months time, once the initial shock dies down, that security support could let its guard down again?

The potential security level of France is really, really good. I believe that they will show a lot more support for the journalists who are the trouble makers. I believe that this problem will not happen, at least for many years. I heard that they’ve added more than 15,000 special security forces.

Do you think France has taken its freedom of expression for granted in the past?

I believe they will appreciate it more. But for the cartoonists living in France, I believe the situation will be much better for them going forward. Already for Charlie Hebdo – now it’s not a small local magazine at all. It has turned into the most famous cartoon magazine in the world.

So what the attackers set out to do – to silence a voice – has actually had the reverse effect? It’s more famous, and more people are reading the cartoons than ever?

It made me so angry – those killers shouting in the streets of Paris ‘we killed Charlie Hebdo’. That voice is always in my head. But now I’m really, really proud because they didn’t kill Charlie Hebdo. They gave it another life. Personally I am not a huge fan of Charlie Hebdo, but that’s not the point. Charlie Hebdo turned into a social symbol that represents freedom of expression.

What do you think about the #jesuischarlie movement? Do you think that people who are using it should understand and support the cartoons?

That was the funny part actually. A lot of people they were saying “Je suis Charlie” and they had no idea what it means or had never read the magazine before. It became a fashion. I even saw at a bag shop – they created this bag with “je suis charlie” written on it. On this fancy bag. [Laughs.] But I love that ‘Charlie’ turned into a general symbol. If people want to support freedom of expression and use “#jesuischarlie” – I love that. And that’s what I felt, that’s what I appreciated.

So do you feel something like that is a positive thing to be putting out into social media?

You know, I am a huge fan of social media in general. And I take social media seriously. In Iran it is totally blocked – but always people find ways.

Why is cartooning important for you?

Cartooning has a power to influence people. You don’t need to write a huge article – just an image can be enough. People appreciate that, because they really love to know things very fast.

In a 2013 interview you were quoted as saying the most dangerous theme an Iranian cartoonist can cover is Islam. Are there any topics that should be off limits to cartoonists?

I don’t believe in any limits. I believe freedom should be without limits, without exception. But I prefer not to draw the prophet Muhammad. Because I don’t need to. I prefer to draw, for example, the Muslim Brotherhood, Al-Qaida, or the Taliban. They have a common problem I’m attacking. I don’t need to draw the prophet Muhammad, because I have no idea how he lived – I’m not a historian.

As a cartoonist how did you respond to the attacks?

I felt a new responsibility. Which was – so they have been killed for what? It forced me to rethink about the importance of freedom of expression. I was witness to how all of my colleagues, as a symbolic act, started to draw and share their cartoons. I received more than 100 in my inbox that day. I did my first cartoon in response at midnight on the same day.

–

Grab a copy of Kianoush’s book Earth’s Visual Diary, available on Amazon.

–

Alice is a filmmaker from Melbourne. She has finally joined the 21st century on Twitter, or you can follow her movements at alicefoulcher.com.