Inside Sydney’s Egyptian Consulate The Morning After Journalist Peter Greste’s Jail Sentence

We work four floors above Egypt's Sydney Consulate. We went downstairs to ask some questions.

Last night at around 6:45 local time, Australian Al Jazeera journalist Peter Greste was sentenced to seven years jail for defaming Egypt and supporting the Muslim Brotherhood, alongside his colleagues Mohamed Fahmy and Baher Mohamed, who received a ten-year sentence.

The news was met with horror, dismay and anger, with world leaders condemning the verdict and politicians putting partisan divisions aside to call for Greste’s release.

Awful news about Peter Greste – journalists should not be jailed for doing their job #FreeAJStaff

— Bill Shorten (@billshortenmp) June 23, 2014

#BoycottEgypt MT @BBCKarenAllen: Our protest from Kabul. #FreeAJStaff pic.twitter.com/3qpy2qrIpy #AJTrial #FreeAJThree

— Jerome Starkey (@jeromestarkey) June 23, 2014

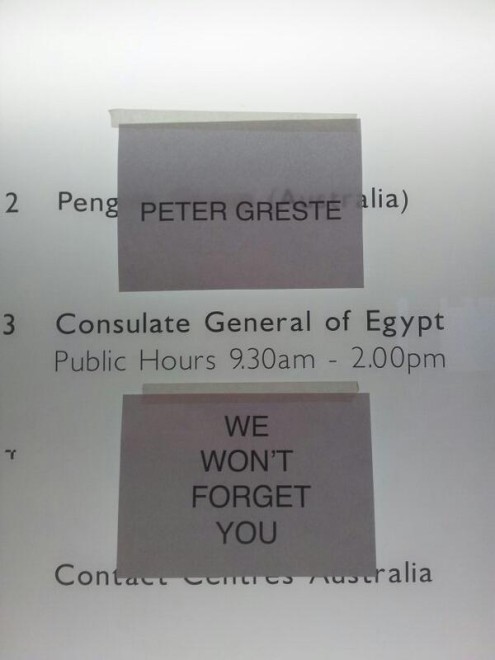

Junkee’s office happens to be four floors above that of Sydney’s Egyptian consulate, on Commonwealth Street in Surry Hills. As people entered the building early this morning for work, this message had been taped onto the front lobby’s signage:

We went down to have a look at what the mood was like in the Consulate, and to see if anyone would answer our questions.

–

Egypt may be in the grip of an authoritarian military dictatorship, but their foreign Consulate offices are almost lovingly daggy. Kitsch posters of the pyramids and the Sphinx are all over the walls, and two big cardboard columns with painted-on hieroglyphs stand at the welcome desk. An old couple are slumped on the waiting area’s wraparound couch, watching the World Cup on a giant flatscreen in the corner.

Surprisingly, there is almost no one here — maybe three or four staff in all, and certainly no angry Australians. The secretary, an older woman who looks unamused, grunts and shuffles off when we ask to speak to someone. A few people trade pained half-smiles and pin their eyes to the soccer game.

Eventually a middle-aged man with slicked-back hair and reading glasses emerges. He is very polite, but does not come out from behind the thick safety glass that separates staff from visitors, bank-style. We shake hands awkwardly through a little hole in the glass.

When asked for comment on the Greste verdict, the man says only that the matter was decided by an Egyptian court. He has nothing to say on the fairness or otherwise of the verdict. That is not his job.

For obvious reasons they keep their political and religious affiliations to themselves, but we learn that all Consulate staff are sent out for stretches of four years at a time. A lot can change in four years. Four years ago Egypt was still under the thumb of long-time dictator Hosni Mubarak, who ruled for almost thirty years, and the Arab Spring wasn’t even on the wind. Mubarak was the Arab Spring’s biggest casualty; he was sentenced to life in prison for failing to prevent the deaths of protesters, and now resides in a military hospital in Cairo.

Egyptians protest in Cairo’s Tahrir Square in January 2011. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Some of the staff only started their jobs in the Consulate two years ago; around the same time Mohammed Morsi was elected Egypt’s President in the country’s first-ever truly democratic elections and the Muslim Brotherhood was legalised for the first time in more than 60 years. After the coup d’etat one year later, led by the commander of the army and current President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, the Muslim Brotherhood was outlawed again. More than 600 people died in the violence that followed. Greste and his colleagues have been jailed for supporting the Muslim Brotherhood, an extremely serious offence in the eyes of Egypt’s current administration.

The verdict that sealed Mubarak’s fate was handed down around the same time some of the staff started their jobs in the Sydney consulate. By the time they return home, the situation in his homeland may be as unrecognisable as the mood of hope and optimism stemming from the revolution in 2011 is unrecognisable now.

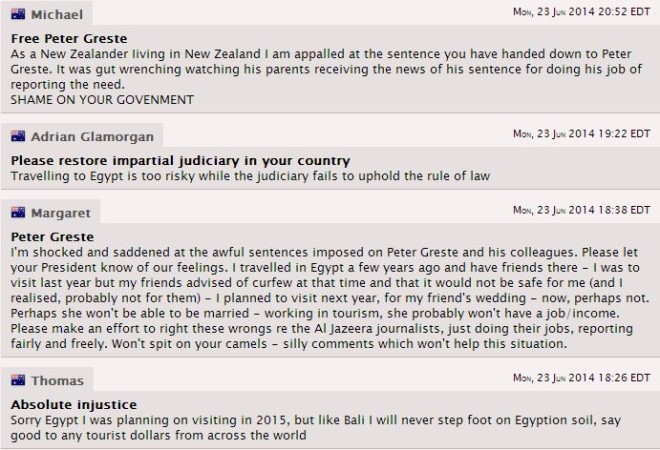

The office is quiet, but the phones aren’t. All morning, people have been ringing in to vent their anger and let the Consulate staff know exactly what they think of Egypt at the moment. Staff have been taking these calls, telling people that the process is not yet finished and the defendants can still appeal the court’s verdict if they wish. But the tone of all those calls is undeniably getting through, as are the comments people are leaving on the Consulate’s page on Embassy Finder: one of the staff admits that “a lot of people are very upset”.

It becomes obvious that, for any number of reasons, the Consulate’s staff are not going to be forthcoming today. They are going to be, in a word, diplomatic. We shake hands with the middle-aged man again through the little hole in the safety glass, and he goes back to work.

A little later we head back down to grab a photo of the daggy front lobby. He is on the office’s tiny balcony, sipping strong black coffee and smoking a cigarette. He denies our request for a photo of the lobby and we may not quote him at all, because the only person in the office who can supply quotes to the media is the Consul-General, Ayman Kamel. He does, however, promise to send through a media release soon.

We shake hands again, properly this time, and leave him to his coffee and cigarette.

–

Feature image from the Overseas Press Club of America via Twitter.