How Facebook Subtly Works To Reinforce Your Prejudices, Without You Even Realising

You're spending a massive amount of time in a giant echo chamber, and it's affecting the way you think.

The war is over. Facebook won.

With 1.19 billion monthly active users, 12 million of them coming from Australia, it’s safe to say that Facebook has a presence in your pocket. Much has been written about the effect the network has on our mood and social behaviour – but does the pale blue ‘f’ actually have an effect on our agency? How does it change or reinforce our political and social biases? More importantly: is it making us racist?

Facebook promulgates a culture in which connectivity, sharing, and belonging reign supreme. In 2013, the journal Computers in Human Behavior published a study by Shannon M Rauch and Kimberley Schanz titled ‘Advancing racism with Facebook’. In it, the authors found that our main motivations for using the site are to find a sense of belonging, and as a space for self-presentation – and that the more we use Facebook, the more likely we are to accept messages we find therein – “particularly messages with overt racist content”.

Another study from the same journal — ‘A tale of two sites: Twitter vs. Facebook and the personality predictors of social media usage’ — put forward the idea that heavy users of Facebook have less natural tendency to seek out cognitive stimulation when they’re scrolling through the platform. So, we log on to Facebook not to learn from and engage with challenging media, but to create an online version of ourselves that’s surrounded by a social network we are in agreement with, in which we can find a sense of belonging.

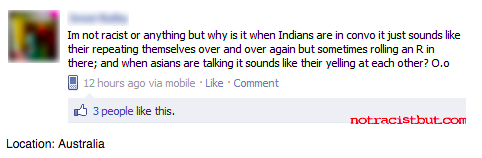

The very structure of Facebook is one that promotes complicity: we “Like”, share and affirm. Rauch and Schanz’s study showed that Facebook users regularly expect they will agree with the content on their feeds, and that they aren’t likely to be actively thinking against the grain when presented with persuasive messages. But we all know that Facebook can be a mixed bag; posts of a perfunctory nature live side by side with passionate declarations about the state of the world, and posts claiming that we should all quit sugar are nestled next to the casually racist comments from someone in your extended family, office, or tute group at uni.

This might not scream cultivator of racist thought right away, but Facebook’s affirmative culture, repetitive presentation of messages, and tendency to get swept away in mob mentality may have the suggestive power to steer our thoughts down an undesirable path.

–

The Filter Bubble

Your identity moulds the media you consume, and the media you consume moulds your identity. The Internet isn’t the same for everyone. Your Facebook and my Facebook have obvious differences — but even if we have friends in common, “Like” the same pages or attend the same events, the frequency at which these bits of information are presented to us is decided by Facebook’s notoriously mysterious algorithm, formerly known as EdgeRank.

You can try your best to curate your digital daily with challenging and insightful information, but if you’re constantly clicking on the greatest cat videos of all time, sooner or later your news feed will start to look like the lady who lived down the road from you as a child and was known for letting cats drink milk from her cereal bowl. Your digital profile doesn’t lie.

This wouldn’t be a problem, except for the fact that message repetition has proven to be a successful persuasion technique when it comes to politics, business, advertising, self-development — pretty much everything.

Internet activist and chief executive of Upworthy Eli Pariser wrote a book on what he calls “the filter bubble”. He says the more we are exposed to messages, the more likely we are to have agreeable feelings towards them. When we feel an affinity with online content there is a higher chance that we will comment on it, or disseminate it through our networks. This action causes Facebook’s algorithms to rank that content higher in your perceived interests, meaning that you will be exposed to it on a more regular basis. And then the cycle repeats.

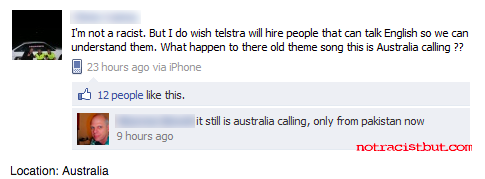

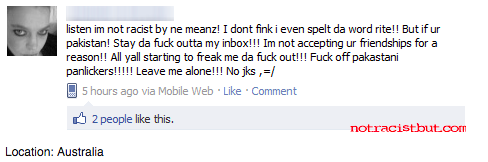

It’s fine if your newsfeed is filled with cats. But Australia’s casual racism problem means the likelihood of someone on your newsfeed dropping racist rhetoric is pretty high — and if someone in their newsfeed agrees, the message will be shared and given algorithmic importance; as their filter bubbles become smaller, counter arguments aren’t shown, and newsfeeds begin to look like this.

–

Strange Bedfellows Under One Banner

The Internet is a place of immediacy and action; hashtags emerge almost instantly in response to a tragedy, hate-crime or poorly-worded tweet, which we replicate and then disseminate to show our solidarity.

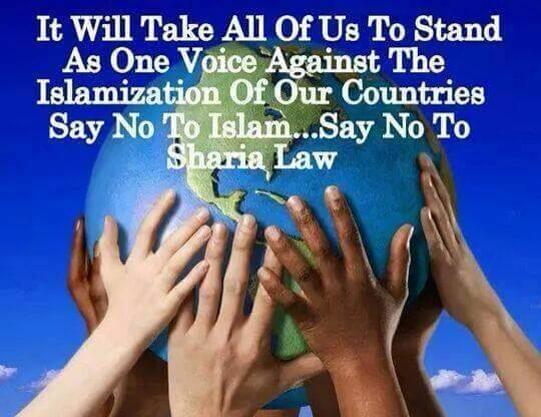

While some are innately positive and mostly unproblematic, like #IllRideWithYou, others soon become a motley crew of ideals and agendas, that have us digitally campaigning for a cause before we fully understand the ins and outs. A lot has already been written about #JeSuisCharlie, and the way that hashtag unwittingly unified empathisers for victims of tragedy with French nationalists, anti-Muslim groups, clicktivists, libertarians, and about 50 percent of your news feed. But it’s interesting to think of the #JeSuisCharlie movement through the lens of Facebook’s culture of compliance and Pariser’s “filter bubble”. Support for #JeSuisCharlie swept through my Facebook feed with rolling enthusiasm, as many jumped on the bandwagon before fully considering its implications. Charlie Hebdo has been criticised for being deliberately antagonistic, but the real problem with #JeSuisCharlie came when the hashtag started being used as a vehicle for sharing Hebdo cartoons that, especially when removed from their satirical and cultural context, were simply offensive.

The overwhelming show of solidarity is understandable. A controversial 2014 study, ‘Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks’, published by The National Academy of Sciences of the USA, found that “emotions expressed by others on Facebook influence our own”. This, working in conjunction with findings from Rauch and Schanz that suggest Facebook users “overestimate the extent to which they agree with their friends on political issues” – coupled with the earlier findings about belonging, and a lack of desire to critically question information presented online — create the perfect breeding ground for social contagion. If you are Charlie, then I’m probably Charlie too. Throw in Pariser’s concept of the ‘filter bubble’ and escaping the crowd contagion of shallow thought becomes increasingly difficult.

The contagion works both ways. When backlash to #JeSuisCharlie began to circulate our Facebook feeds, we found ourselves once again agreeing with our digital communities, taking away the little black and white box that had temporarily become our profile picture, and questioning whether we had just partaken in, or perpetuated racist sentiment. It was a complicated time for everyone.

–

Is Water Halal Certified?

Last year, public health organisation beyond blue launched the campaign ‘Stop. Think. Respect’, which aimed to highlight and combat Australia’s invisible discrimination issue.

The campaign is justified: one in five Australians will experience racism in their lifetime, and this number is significantly higher for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, of whom 75 percent will experience racism in their lifetime. Our own Attorney-General believes that we have the right to be bigots — the right to be intolerant towards people who have differing opinions towards ours. Racism in Australia is real.

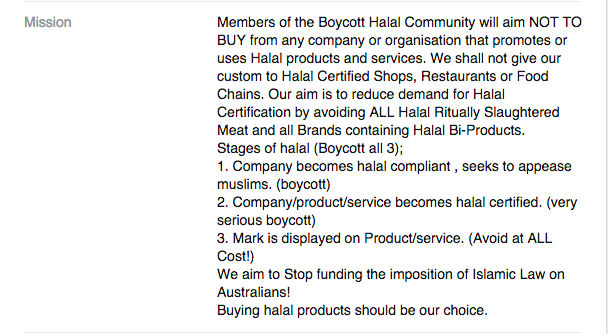

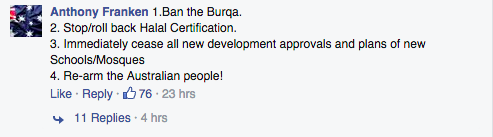

While the ‘Man Dehydrates After Discovering Water Is Halal Certified’ story was a joke, there’s a strong anti-halal movement growing in Australia. The Facebook group Boycott Halal In Australia currently has 66,124 members who all pledge, “Not [to] buy halal products & services, because they fund Islamic expansion in Australia”. They would also like “Compulsory singing of our National Anthem, weekly in every school in Australia” — and I’m going to hazard a guess that #TeamAustralia was a celebrated concept around the virtual water cooler.

Boycott Halal In Australia openly promulgate racist sentiment, but it’s the victim mentality they adopt that has the potential to do the most insidious damage. Rauch and Schanz’s aforementioned study found that taking a victim stance, as opposed to one of superiority, is more persuasive when propagating racial bigotry.

The anonymity of the Internet has a disinhibiting effect on users, which has been tied to increased displays of racism; while the group does have a disclaimer about offensive comments, all the elements are there to make it a back-slapping petri dish of racial hate.

–

So: Is Facebook Making You Racist?

In the same way that you can’t ‘catch homosexuality’ from listening to Lady Gaga, skateboarding or sharing a Coke, simply logging onto Facebook probably won’t turn you into a raging racist. But it is important to acknowledge the power structures within which we operate daily. Minus the giant fields of pods growing humans, Facebook is like a modern day Matrix. We are continually plugged in, and even a slight change in programming has a very real potential to alter not only our base emotions, but our deep seated ideologies as well.

–

Bindi is a former Junkee intern. Based in Sydney, she is studying media/communications at UNSW. In her spare time she’s a freelance content creator for FBi Radio and Your Friends House. You can follow her witty one liners on Twitter at @BindiDonnelly.