How David Fincher’s ‘Gone Girl’ Is Better Than The Book

The Cool Girl meets the Cool Director, and it totally works.

I didn’t like Gillian Flynn’s best-selling 2012 novel Gone Girl. “I really struggled through the first half of the book trying to care about these two unpleasant, self-indulgent people,” I wrote at the time. “I didn’t want to read about their stupid lives. I disliked their ‘voices’.”

I liked David Fincher’s film adaptation much more.

Amy Elliott Dunne (Rosamund Pike) is an uptight, unemployed magazine writer who goes missing on her fifth wedding anniversary, after her craven, equally laid-off husband Nick Dunne (Ben Affleck) had unilaterally moved them from a cosy New York brownstone to a rented McMansion in his economically ravaged Missouri hometown. Scripted by Flynn, and hewing closely to her novel, it’s funny in a brittle, grim way, getting more melodramatic as it goes.

While the book immerses the reader in Nick’s and Amy’s equally unreliable narration, Fincher grants more distance. I came away with a clear sense that likeability – or the lack thereof – is itself the story’s theme. Gone Girl is often interpreted as a commentary on marriage, misogyny, psychopathy, media circuses or post-GFC decay, but Fincher’s film highlights that our ability to successfully navigate social institutions and intimate relationships alike depends on how amiable we can make ourselves seem.

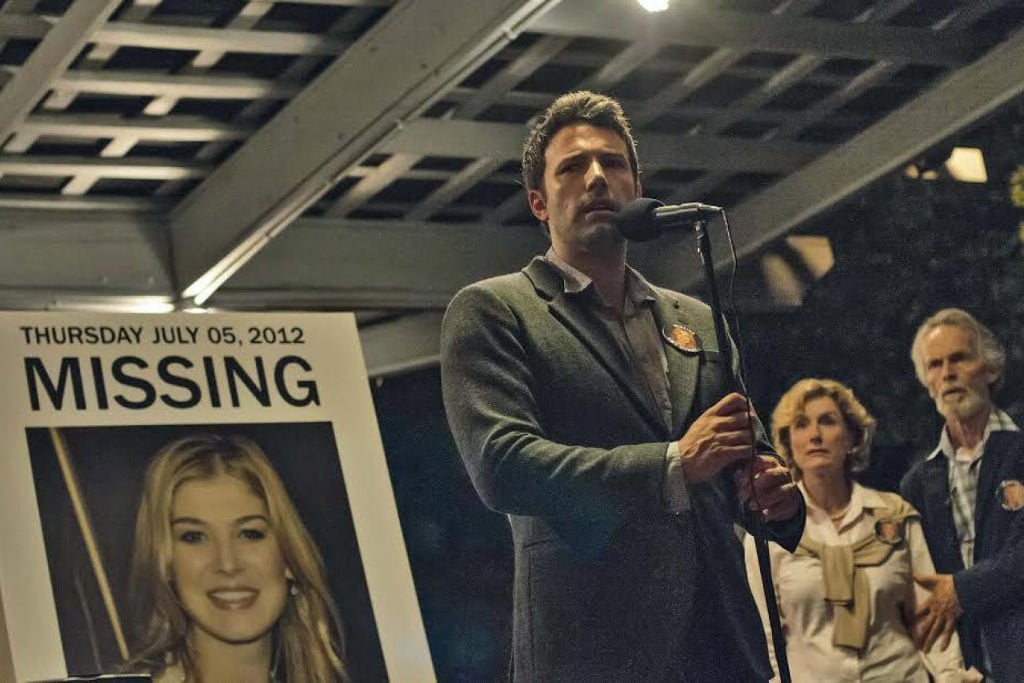

As Detective Rhonda Boney (Kim Dickens) and her droll assistant Officer Jim Gilpin (Patrick Fugit) investigate Amy’s disappearance, and an increasingly intrusive media pack looks for easy moral plays, Nick brings suspicion upon himself by not really seeming that devastated by Amy’s disappearance, and foolishly being photographed wearing a shit-eating grin beside his wife’s MISSING poster.

Truly, Affleck was born to play this role!

Cool Girls And Cool Directors

In the novel, Gillian Flynn famously deconstructs a relationship trope Amy calls the Cool Girl. This is a role women perform in order to appeal to men: an effortlessly sexy, goofy, bawdy girl who shares all her man’s interests, and never nags or challenges him. The film presents this speech economically in voiceover as Amy is driving. Alone, stuffing her face with junk food, she sneers at other women drivers, dismissing their likeability as a pathetic pantomime.

Nick’s tomboyish twin sister Margo (Carrie Coon), with whom he now runs an ironic dive bar, is a kind of platonic Cool Girl. Margo drinks with Nick, jokes lewdly that he should give Amy some deep dicking as the ‘wood’ present for their wedding anniversary, and lets him crash on her couch. Margo is Nick’s other half – his staunch supporter and his conscience.

Amy isn’t “cool”. She’s cold. Pike’s performance is unsettling because it’s so watchful; her eyes stare dully like a shark’s. It’s the perfect match for Fincher’s precise, dispassionate direction; Gone Girl is set during a Missouri summer, but Fincher might as well have shot it in a refrigerator.

If the Cool Girl archetype is an artifice intended to flatter men, perhaps the cool style of Fincher and his fellow contemporary auteurs – among them Christopher Nolan, Paul Thomas Anderson, Nicolas Winding Refn and Darren Aronofsky – plays to the aesthetic predispositions of (mostly male) cinema enthusiasts. So, much as the film unpicks the Cool Girl trope, perhaps the hilariously uncool moments that fizz with increasing absurdity through the calm waters of Gone Girl are deliberately intended to disrupt audience expectations of a stylish thriller. (Why so serious?)

There’s especially rich comedy from Amy’s maniacal parents (David Clennon and Lisa Banes), who fictionalised their daughter as the overachieving heroine of the bestselling Amazing Amy children’s books. And Amy’s wealthy ex-boyfriend Desi Collings (Neil Patrick Harris) feels pasted in from a Noel Coward farce. At one point, Desi perks up at the prospect of travelling to Greece: “Octopus and Scrabble?”

The film’s actual coolest character is Nick’s lawyer, Tanner Bolt (Tyler Perry). Dude is just chilling. He’s unflappable. “You two are the most fucked-up people I have ever met, and I specialise in fucked-up people,” he says delightedly.

Yet Amy’s own Cool Girl performance – with which she reckons she won Nick – is unconvincing on many levels. “I really like you, Nick Dunne,” she announces ludicrously as he’s eating her out. I almost aerosol’d my mouthful of coffee.

Bad Bitches And Basic Instincts

While we’re happy to read and watch stories about male antiheroes, we demand likeability from women writers and characters. “To me, that puts a very, very small window on what feminism is,” Flynn told The Guardian last May. “In literature, [women] can be dismissably bad – trampy, vampy, bitchy types – but there’s still a big pushback against the idea that women can be just pragmatically evil, bad and selfish”.

In the intricacy of its plot (let a thousand spoiler whinges bloom!), the precision of its cinematography, and Pike’s icy blondeness, Gone Girl superficially resembles a Hitchcock film. There’s a certain film noir quality to the methodical, deadpan detectives, and the way even the best-laid plans go awry. Yet a lurid, De Palma-meets-Verhoeven delight in human grotesquerie also peeps through Fincher’s fastidiousness, like the “faeces” Amy’s mum claims she can “literally” smell – a moment that instantly reminded me of Beth Grant’s Sparkle Motion mom in Donnie Darko.

In the same way that 1980s and 1990s erotic thrillers mined disquiet about women’s increased economic power and sexual agency, Gone Girl exploits the current anti-feminist backlash over rape allegations. The film panics that it’s easy for women to deceptively claim that consensual sex was rape, acting as the sexual aggressors ‘in the moment’ but then retrospectively faking evidence of sexual assault. But here, it’s part of the erotic thriller’s paranoid genre trappings – in real life, such nefarious plans are as common as your girlfriend’s housemate administering death by stiletto, or a high-powered career woman ironically getting into cooking.

This film’s gormless male characters echo Michael Douglas, the erotic thriller’s “bare-bottomed prince” who in three different films knowingly indulged in illicit sex and yet was a convincingly innocent victim of his spurned lover’s vengeance.

Ultimately, what makes me enjoy Gone Girl more than its source novel is the way it translated an essentially subjective and unreliable narrative to the screen with unsentimental clarity. The film signals the novel’s major twists using tonal shifts from self-serious crime drama to erotic thriller, and finally into all-out farce. And the protagonists’ unlikeability comes to seem no longer tedious, but perversely funny.

“I’m the cunt you married,” Amy exults to Nick as he grips her in a choke hold. It’s awful. But it’s also triumphant, because in moments like these Nick is no longer trying and failing to be a Good Guy, and Amy is completely liberated from being a Cool Girl. The façade is gone. And I liked it.

–

Gone Girl is in Australian cinemas now.

–

Mel Campbell is a freelance journalist and cultural critic. She blogs on style, history and culture at Footpath Zeitgeist and tweets at@incrediblemelk.