‘Girls’ Recap: We All Know This Kind Of Man

This episode was clever and sympathetic and clear-eyed about one of the most contentious issues of the moment.

This recap discusses sexual assault.

–

Nothing is as reliable as disappointment. Not the huge, soul-crushing disappointment of anticipated joy being snatched away like an Oscar handed to you moments before by Warren Beatty; but the everyday disappointment that happens when you know what to expect out of a situation, but allow yourself to peek at the possibility of pleasant surprise against your better judgement.

One of the most prominent among the sub-genres of that particularly commonplace sort of letdown is the discovery that a man you know or like or admire professionally is A Creep. Women have long tried to look after one another in professional environments scattered with men like this, but the culture of public calling-out still feels like a relatively new development.

Women are speaking out about their experiences of sexism at major corporations and in whole industries, and some are directly accusing men by name of harassment or assault. We’re grappling with the tension that exists between the knowledge that sexism and harassment definitely happen, and the worn old he-said/she-said conundrum that hangs over any accusation of inappropriate grappling directed at an individual.

Of course, we’re also in an era where (sigh deeply, and say it with me) a man can be recorded admitting to habitual sexual assault and still be elected President of the United States. It still feels weird that that happened in the same year where accused serial rapist Bill Cosby was widely acknowledged as such, but there we are.

This week’s episode of Girls would have been written and filmed well before Trump won the election, and before pussy-grabbing became the grossest colloquialism of the year — but it was written and filmed in the context of a growing (and largely internet-based) call-out culture. This is both a source of strength and support to many women who’ve been harassed or assaulted, and a new reason for a certain kind of man to feel aggrieved with a social and systemic power balance that’s shifting ever so slowly (SO slowly) away from him.

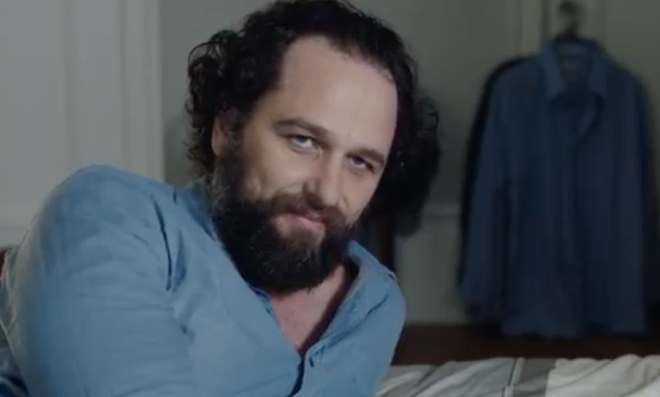

This is the dynamic Girls interrogates in a theatrical two-hander that’s talky and clever and sympathetic and clear-eyed about its biases. Chuck (Matthew Rhys, who is phenomenal in this) is the author of at least six acclaimed novels — a much-awarded, well-off, a-little-balding-but-not-yet-old man of letters who hangs out with Toni Morrison — and yet it’s entirely believable that this is also a man would have a “deep Google Alert” on his own name set up, that he would read a “We need to talk about X”-style piece on a “niche feminist website”.

It’s not a stretch to see him summon the piece’s young female writer (Hannah) to his nice apartment so he could defend his reputation and character; that he would be condescending and peevish and primarily concerned with his own feelings. We all know this kind of man.

Of course you <3 Chuck, buddy.

“Do you know this young woman?” he asks Hannah, speaking about his accuser with a familiar subtext. It’s heavy with the idea that people (particularly young feminist women) who write about sexual allegations they have no first-hand knowledge of have no business doing so, and are jumping on bandwagons to further an agenda. (Yes, that nefarious agenda of not wanting women to be harassed any more).

When Hannah explains herself in the kitchen later, he appears to understand that familiarity with the situation itself isn’t always necessary. Every woman and girl is familiar with the power dynamic Chuck’s accuser, Denise, describes. He then pulls out the tired and laughable argument that men wanting to fuck us actually makes women more powerful in that situation. But he already knows, even as Hannah coolly explains it, that despite whatever flash of helplessness a man might feel in a particular moment of desire, there are always levels of power more potent than the ability to withhold our enthusiastic consent.

Lena Dunham herself is in the rare position of being both a young female survivor of sexual assault and also having a dedicated crew of internet commenters who will bellyflop into the bottom half of any page with her name on it to bay that she’s “a self-confessed child molester”. They usually do this with a vehemence similar to both those who proclaim to have boycotted Woody Allen, and those who want the world to know that they do not find Lena Dunham fuckable. (Here is not the place to debate the size of that Venn overlap.)

It’s no coincidence that Woody Allen is literally pictured as a saint in Chuck’s house.

While there’s nuance to the story of childish experimentation Dunham was trying to tell in that story about her sister, the language she used to frame it was either thoughtlessly or deliberately provocative or both, and she does seem to regret that. At any rate, as much as she’s on the side of advocating for women suffering under a power imbalance, she might also have a little conditional sympathy for the mental state of a famous man who finds himself branded an abuser. It certainly feels like she fed some of that into the crackling dialogue between Chuck and Hannah. His anguish at the idea that people might believe the young woman’s story isn’t necessarily entirely feigned, and isn’t even at odds with the eventual reveal that he’s exactly the disingenuous lech Denise and his other accusers say he is.

Of course, the brilliance of this is in Rhys’ performance — as a man who’s difficult and clever and pitiable, with easy insight Hannah falls for — as well as in the tension between the obvious conclusion (he is a gross sex pest playing a weird power game with a young woman who called him on his shit) and the audience’s desire for something more complex (he’s a sad, lonely dude in a decade-long hangover from being drunk with success and attention and he wants to explain himself but ends up learning something about how to relate to women better).

We are buoyed along, as is Hannah, by the tantalising notion that he’s not just a creepy, shitty dude; that he can still be redeemed by something as simple having a conversation and gaining a deeper understanding of other people. And then the ugly truth flops its dick out onto our leg.

(Dick redacted)

The script and execution of ‘American Bitch’ is so absorbing, so funny and focused and adept at shading in a detailed map of an explorable grey area, that it’s not until afterwards that I realised how distant this firmly articulate, self-assured Hannah feels from the one who sulked out of surf class in the premiere. The New Yorker’s Emily Nussbaum felt it was too out of character, but I’m not so sure.

The Hannah who gets herself a beverage despite one not being offered, who allows herself to be seduced brain-first by compliments and conversation into trusting this man she publicly labelled a sleaze, who touches Chuck’s dick just because it’s there and then leaps up in revulsion at herself and at him, is the same smart, vulnerable person who wears, does and says whatever the fuck she feels like. She’s the same woman who we’ve watched grow out of letting Adam treat her like crap as she endured the various ways he’s hurt her over the past five years, and who calmly helped Marnie climb off the psychosexual hamster wheel last week before hauling the bloodied douche into a convertible. That’s progress.

Doing everything “for the story” doesn’t always cut it anymore.

Girls’ annual takes on the bottle episode are, without exception, always among the show’s best, and usually the highlight of the season: think the Patrick Wilson episode, last season’s Marnie adventure, Hannah’s sit-in on her return from Iowa (and yearn for the Shosh-in-Tokyo episode that could have been). It might make us wonder why they haven’t used that laser focus more often — but if they had, it might not land as well it does.

The brilliant final shot, as Hannah wanders dazed into the street and a small stream of long-haired, faceless women start to pour into the creep’s building behind her, is both surreal and chillingly relevant in a way that needs no unpacking: no matter how many women stand up for themselves, we’re going to keep hearing these stories, one after another, for a long time.

–

Girls is on Showcase at 8.30pm Wednesday nights.

–

Caitlin Welsh is a freelance writer who tweets from @caitlin_welsh. Read her Girls recaps here.