Why Do We Expect Our Favourite Kids’ Stories To Make Good Films?

From 'The BFG' to Dr Seuss: some stories are better left on the page.

Roald Dahl’s Big Friendly Giant is an intimately familiar presence. We’ve been taught to love this type of character: a simple, moral force for good with a sturdy heft to match the main character’s hubris. His Northern English accent conjures the large and rustically good-humoured and rough-mannered companions from Dickens (such as Great Expectations’ Joe Gargery and David Copperfield’s Mr. Peggotty) and Rowling (who surely cribbed a little from Dahl’s work when creating Hagrid).

The BFG of Spielberg’s new film, adapted by E.T. writer Melissa Mathison, is great. Mark Rylance delivers a beautifully calm and endearing performance, and you can really feel the years of lonesomeness that haunt this kind ginormous runt, trapped in the land of giants with a gaggle of bulky, dim-witted bullies. His vocal work is a delight, making the most of the Giant’s malapropisms — one of the highlights of the book for young readers.

But The BFG itself is a strange creature. The film seems to have no idea what to do with its central character, or how to transform the slim plot found in Dahl’s novel into a movie. It’s one thing to introduce us to a magical new world, but something should probably happen once we get there.

–

The Problem With Adaptation

Cinematic adaptations of books tend to follow one of two routes. They either retain the majority of ‘bound motifs’ (plot points clinging to the narrative structure in an effort not to omit any audience member’s favourite moment) or they concentrate on the ‘free motifs’ that have greater impact on the stories’ themes and tone.

In a film and TV landscape littered with pre-existing stories and characters (reboots and remakes bring with them handy built-in audience awareness) the choice is between narrative and tonal fidelity is a hard one for writers and directors; they face intense scrutiny from viewers and the media. There’s a reason why there are hundreds of angry comments attached to articles on ‘Why Civil War Gets Spiderman Exactly Right’, and ‘How Game of Thrones Ruined The Best Character In The Book’: people are invested. That doesn’t mean things can’t succeed. Classic novels often make great mini-series as they delve into each plot point and sketch out the whole world, and moody and taut post-modern head fucks like Fight Club and American Psycho are possibly even better on the screen than the page.

But this can be more complicated when adapting kid lit. These stories aren’t often known for complicated plot or emotional complexity, instead delivering simple (and often astute) concepts on both fronts. If you’re adapting the work of Roald Dahl and worrying about bound motifs, you come in at quite an advantage. Dahl defined good writing as the ability to make a “scene come alive in the reader’s mind”, and there are probably singular scenes that pop into your mind when remembering his stories.

His books are full of moments of triumphant come-uppance, contrasted with others of dreadful tension. Whether it’s hiding backstage at the terrifying witch’s meeting or watching the obnoxious Violet Beauregarde blow up like a balloon, there are plenty of instances defined by strong visuals and clear emotional relatability.

You’re damn right you deserve all this for being the kind of kid who chews gum.

It’s understandable why the work of Dr Seuss, seems equally as enticing. We all remember the crazy creatures, odd-bod landscapes and deliciously playful language, right? Some of his stories make narrative sense to adapt. The Grinch is a standard morality play, and The Lorax is a cautionary tale. Neither, however, possesses a strong three-act structure, instead hewing closer to Aesop’s Fables, where characters learn a simple lesson. No one is suggesting we make a two-hour film about the tortoise and the hare (although someone somewhere is definitely pitching an Aesop’s interwoven 20-movie universe experience, with Chris Pratt voicing the Hare).

With that in mind it’s tough to know what the makers of The Cat In The Hat were thinking when trying to bring that minimalist narrative to the big screen (besides $$$). Seuss’ recollections on the creation of the The Cat In The Hat are numerously different, and in true Seussian fashion, often contain completely invented illiterate members of his own family named Oslo and Norval. What is known for sure is that the author was frustrated with writing for young readers and being told his vocabulary was too expansive, and the publishing industry was also keen for primer books that were a step up in quality and creativity from the classic Dick and Jane titles.

With this, Seuss took a list of roughly 300 words that first graders should know, and whittled out a book that used only 236 different words. His inspiration for the story came from combining the first pair of rhymes available on the list — cat and hat. The results were genius, sold in the millions, and a classic was born. But that definitely doesn’t make a good premise for a film.

–

The Best And Worst Of The Genre

Cinema can be both entertaining and educational, but rarely is a blockbuster kids comedy a substitute, or suitable paratext, for a learn-to-read book. It’s no surprise then that the big screen adaptation of Cat struggled. It crammed in subplot on top of subplot, hyped up the familiar Seuss iconography until it became technicolour Stepford dystopia, and dumped atonal goofiness care of Alec Baldwin and Sean Hayes into a movie already staggering under the weight of Mike Myers’ desperate uncanny valley feline flop sweat.

The reason that Seuss didn’t see fit to include “military academy”, “hand sanitizer”, or “constitutional monarchy” in his book had little to do with their absence from his approved word list, yet these phrases all feature onscreen in the film’s first ten minutes.

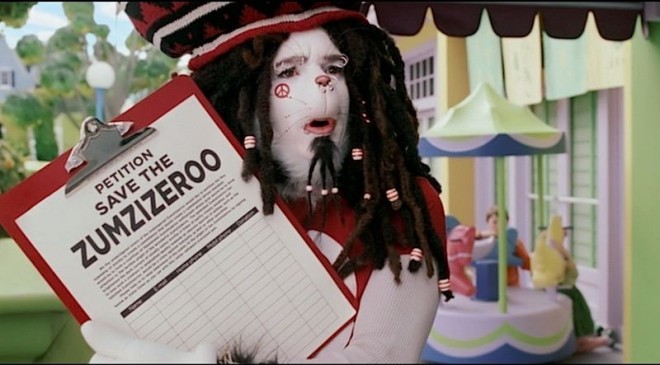

Seuss, a famous conservationist, would surely have loved this pointed satirical take on the white dreadlocked college protestor as much as young moviegoers did. Such a worthwhile project for the film’s costume department.

What the film does attempt to capture is the precarious balance between excitement and danger that accompanies kids’ unsupervised playtime. One of the reasons children respond so well to chaos in the context of literature, whether it’s adventures gone awry or toilet humour, is that they have so little control in their lives. Choosing books that push the boundaries of what is acceptable gives us the opportunity to both rebel and act autonomously in a safe space, while testing our daring and comfort levels.

This is the same set of feelings explored in Where The Wild Things Are. It creates a world where imagination can bring extreme joy, which can also leave you feeling invincible and then turn you into a monster, all before it goes a little too far and someone loses an arm. While no one actually gets de-limbed in Maurice Sendak’s classic picture book, they do in Spike Jonze’s 2009 adaptation, and it’s such a pure exaggeration of the original’s sense of primal exhilaration that it doesn’t feel gratuitous at all.

Just your standard depressive narcissist monster and his enabling dismembered bird friend. You know, for kids!

Jonze’s film might be a perfect example of using free motifs to adapt a book. The plot points of the original are extermely minimal. Max, the protagonist, acts up, has a fight with his mum, imagines a world of monsters, enjoys some roughhousing, and heads home. Rather than ramp up the run time with extraneous action and chatter, Jonze simply allows the emotion more room to breathe, and playtime becomes the epic emotional landscape that we can all remember.

Speaking recently at Vivid Ideas this month, Jonze recounted how anxious the studios were about a children’s film about childhood — about how stranger, darker, and sadder childhood was than is ever shown in films for children. It’s those extra levels of weird and wild that make the film work.

–

Why The BFG Fails

The BFG is less strange, less dark, and less sad than the book on which it’s based. Spielberg for once lives up to his unfair wrap as a Hollywood handwringer, toning down the weirdness of the BFG, the miserable circumstances of protagonist Sophie’s orphanage past, and the amount of farting that surely has endeared the book to generations past. I mean, the 1989 animated version even turned the scene into an earworm celebration of flatulence. Give the kids their farts, Steve.

We respond so heavily to the books of our childhood because they encourage our imaginations to fill in the gaps between illustrations and simple scenarios, creating storytellers of us all. But this is one of the reasons why big screen adaptations so rarely work. Without time for us to imagine the nefarious deeds of the giants, or to vocally play with tongue-tied miss-mutterings of the BFG, or to conjure the immense satisfaction of eating 30 pieces of small toast at once, the story falls flat. The camera skims over the details that delight us when reading.

Spielberg, who has proven he can do outlandish imagination, unlikely childhood friendships, and thrilling spectacle, delivers a page-by-page reproduction of a book that’s perhaps best left to the adaptive efforts of a child’s fertile mind.

–

The BFG is in cinemas from June 30.

–

Matt Roden works at non-profit writing centre Sydney Story Factory and co-hosts Confession Booth. His illustration and design work can be seen here.