Enough Sympathy To Go Around: Social Media And The Boston Bombings

Even as the dust was still settling on Boston, Twitter was ablaze with recriminations, minimising tragedy in the same shallow breath as it accused the media of doing the same.

Within minutes of the two explosions that went off in shouting distance of the closing line of yesterday’s Boston Marathon, killing three and injuring over a hundred, the double-edged sword of social media had been drawn.

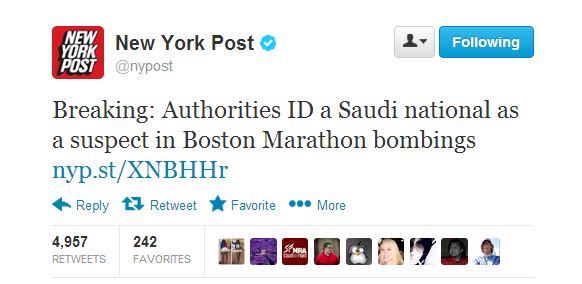

On the one hand, Twitter and Facebook users were there at the scene, offering sanctuary to those afflicted or trying to disseminate information traditional news sources hadn’t had enough time to vet and take to air. Already, social media has been widely lauded as a key factor in the success of the emergency response to the attack, as well. On the other hand, though, it wasn’t long before the redoubtable New York Post threw caution to the wind by tweeting that a Saudi man was being held in custody as a “person of interest.”

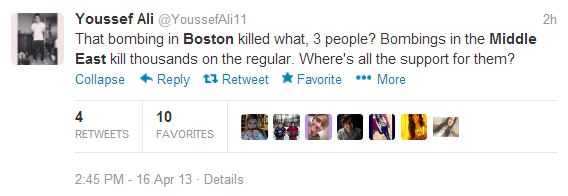

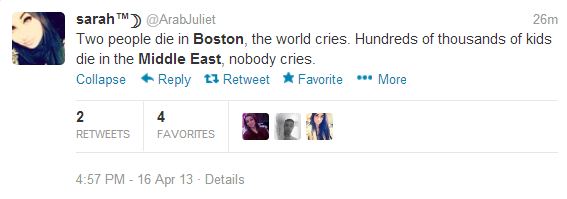

The usual armchair commandos started rattling their sabres at the usual targets, and the conspiracy theorists almost immediately proclaimed it yet another of President Obama’s seemingly endless false flag operations. Meanwhile, numerous social media users started posting links pointing out that what had happened during a Massachusetts running race didn’t amount to much compared to the destruction the United States military has wrought overseas (for numerous examples, search “Boston” and “Middle East” on Twitter).

In terms of sheer numbers, of course they had a point — but with the dust literally still settling in Boston, could the implicit recriminations not have waited?

It would be uncharitable to assume the worst of these social media warriors, to assume that they derived any kind of joy from the suffering of the marathon runners, spectators, photographers and reporters who were victims of the blast. No; they just wanted to make it known that other innocent people have died, time and again, in places that don’t have the kind of global media presence the USA is afforded. Undoubtedly, they have as much sympathy for the victims of the Boston attack as anyone else. But it would not be remiss to say that in seeking to draw attention to the media’s hypocrisy, they have made hypocrites of themselves, inadvertently minimising Boston’s tragedy in the same way they accuse the media of minimising tragedies elsewhere.

Part of what enables this line of thinking, at least in Australia, is our close but thorny relationship with the United States. We are fascinated with America to the point of obsession; while we hang out in speakeasy-style bars, eating pulled pork sliders and drinking Sailor Jerry, we’re always waiting for the giant to take a tumble, and with any luck injure itself on the way down. We derive considerable benefit from our close military and cultural association with the United States, but the alliance has extracted an equally considerable cost from us. So our ambivalence is understandable: aside from anything else, we Australians like to think we’re naturally suspicious of the tall-poppy, the big-noter — and the United States, with its driving concepts of manifest destiny and American exceptionalism, is perhaps the biggest big-noter of all.

From that perspective, a touch of knee-jerk anti-Americanism is to be expected, but it still exposes one of the internal contradictions of modern progressive thought: while we are frequently willing to apply the principles of moral relativism to world affairs, we make an exception when it comes to the United States, abruptly adopting a zero-sum mentality that would make a Tea Party Republican blush. From this point of view, if one expresses support for and solidarity with the victims of the Boston bombs, one is necessarily saying they don’t care about the victims of quasi-legal drone strikes in Pakistan. Such atrocities, it is asserted on Facebook and Twitter, are not reported (although these assertions are frequently accompanied by a link to a major news source doing just that). Notable in its absence is the social media presence of these atrocities when they actually happen; they are stored up until they can be used as a counterweight to Boston, or Sandy Hook, Virginia Tech, the World Trade Centre. It can’t help but look like the deaths of all those people in the Middle East only really matter when they’re a convenient boot with which to kick America while it’s down.

To be clear, the fallout from the United States’ foreign policy over the last half century or more is an extremely grave matter. Far from ushering in a glorious new era of global understanding, the election of Barack Obama in 2008 prefigured an escalation of America’s overseas military presence, albeit a quieter and arguably more precise brand of it.

Hardly a day goes by when we don’t hear about the repercussions of the campaigns in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya: children and wedding revellers killed by drone strikes; mosques bombed by sectarian fanatics; the rights of women curtailed even further than they were under the old regimes. We should be reminded of these things as members of humanity, let alone members of the Coalition of the Willing. But the notion that what happened in Boston represents some kind of universal balancing act, meant to show the United States that its chickens have once more come home to roost, should fill us with revulsion. This is no evening of the score, no act of righteous vengeance; it is simply one more human tragedy piled on top of far too many others.

–

Rob Newcombe is a freelance pop culture journalist whose work has appeared in Rave Magazine and The Brag.

Feature image from Boston Globe via Getty.