This Art Isn’t For You: Why White Men Need To Stay In Their Lane

If it’s not about you, don’t make it about you.

“It’s not for you.” Not only is this one of Camp Cope’s best-known refrains — from the standalone single ‘Keep Growing’ — but it also recently served as a message to cis white men who were thinking of reviewing How to Socialise and Make Friends, the second album by the Melbourne trio.

Vocalist/guitarist Georgia Maq was the first to tweet about it, with her bandmates — bassist Kelly-Dawn Hellmrich and drummer Sarah Thompson — quickly echoing the same sentiment.

can cis white men stop reviewing our album. it’s not for you.

— goldsoundz_ (@GeorgiaMaq) February 28, 2018

i would MUCH rather a woman or a queer person write the review, i’d MUCH rather that person get exposure and get paid for their writing. they deserve it more.

— goldsoundz_ (@GeorgiaMaq) February 28, 2018

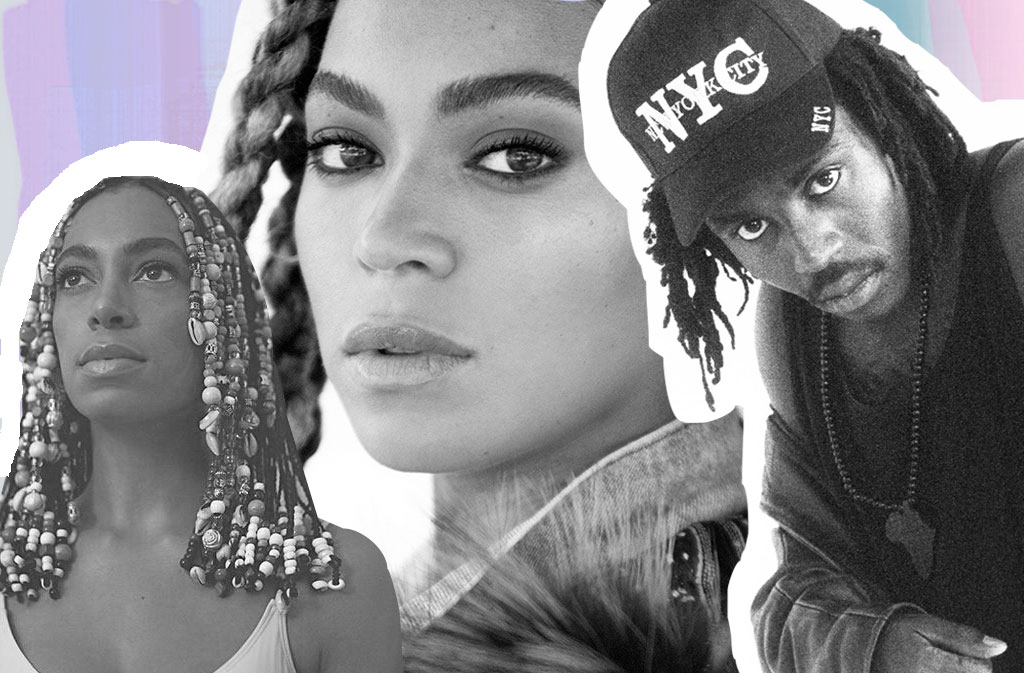

Camp Cope’s statement coincidentally came at the same time as a pair of similar events. Before Maq’s tweet, Black Comedy writer Nayuka Gorrie had tweeted about not trusting white writers with interviewing Solange Knowles ahead of her appearance at Vivid Live this June.

Then, not long after Maq’s tweet, a new book called Deadly Woman Blues — penned by white male author Clinton Walker — was withdrawn from sale by its publisher just weeks after hitting shelves due to major factual inaccuracies and a considerable lack of communication with his subject matter.

All of this, naturally, has struck a nerve with the sub-species of online personas that rapper Briggs has lovingly referred to as the “Angler Saxons” — furious white men whose profile picture is invariably them out fishing. “Oh what, so we’re not allowed to like something now?” they bemoan. “We can’t have opinion on something? When will people realise that the most oppressed voice in society is that of the white male?”

Well, strap in, Anglers. Allow me, a fellow white guy, to reel you into a few home truths. Because it shouldn’t have to be the job of women to educate men on basic human decency.

#1. Privilege Is Something That Needs To Be Acknowledged

The art that is made by those outside of the bubble of white male privilege was not made for you. That doesn’t mean you can’t enjoy it, that you can’t support it or even that it is immune from any degree of critique. You can do all three if you want — you’re “allowed” to, so to speak.

With it, however, must come the acknowledgement that you are not on a level playing field.

That there is every chance that you are speaking over someone who is intrinsically closer to the art itself — whether that’s Camp Cope, Solange or the black Australian women Walker was supposedly trying to tell the story of in Deadly Woman Blues. Whatever your thoughts are on records like How to Socialise and Make Friends or A Seat at the Table, you must consider your own place in society.

Just because there’s a call for girls to be at the front, doesn’t mean you have to leave the crowd. If you’re going to stick around, though, remember that this art is being made for others. It’s for their struggle, for their growth and development, for their own self-reflection. Maybe you can get something out of that in your own way — and that’s great.

Don’t think, though, that this gives you free reign to shift the dialogue to centre on yourself. If it’s not about you, don’t make it about you.

#2. If You’re Writing About These Issues, Handle Them With Respect

Clinton Walker is the latest in a long line of white male writers to handle women and people of colour irresponsibly.

Take, for instance, Ian Church’s misguided analysis of PJ Harvey (“she can hold her own with the boys”), or Bruce Elder’s condescending review of Yothu Yindi back in January (“although the predominantly Aboriginal audience genuinely enjoyed the experience, it was a reminder that trying to revisit a previous, golden moment never really works”). By painting these women and people of colour as inherently inferior, the supposed compliments being paid about the artist’s work come off as backhanded and passive-aggressive.

If you’re a white male writer and are tasked with reviewing or interviewing an artist of this ilk, there’s a lot of things you need to take into consideration. For one, never attempt to speak on behalf of the artist — simply prompt them and listen.

By the same token, don’t expect marginalised people to do all the heavy lifting. Take into account what they are saying, why they are saying it and what it means to be saying it. Familiarise yourself with the subject matter and ensure that you have your facts straight. Ensure that you are not standing on the proverbial platform — only that you are offering one up.

This, in particular, is where Walker went so horribly wrong with Deadly Woman Blues. As detailed in an article by Professor Marcia Langton on The Conversation, Walker distorts historical truths and in some cases did not speak to the women he was biographically detailing at all. It’s seemingly done to fit into some sort of narrative structure Walker has already assembled in his mind, which is wildly irresponsible and a total abuse of the platform Walker has been afforded.

Look at Deadly Woman Blues as the exact opposite way to conduct yourself in this position.

You would think ‘nothing about us without us’ would have sunk in by now, but apparently not. https://t.co/b75yBGeeKh

— Bridget Brennan (@bridgeyb) March 7, 2018

#3. Sometimes, You Need To Give Up Your Seat

If it’s clear that your perspective is not relevant, consider removing yourself entirely from the equation.

Before you throw your arms up and scream to the nearest Latham or Devine about how this is political correctness gone mad, understand that there are times where this is an entirely healthy thing to do. By ensuring a range of knowledgeable voices are discussing the text — an album, a film, a performance — you’re bound to learn a lot more than you would by trying to assert yourself as an authoritative voice.

This is a matter of accountability and responsibility. If you genuinely think cis white men are somehow being silenced, think about why it is you’ve appointed yourself as some sort of representative.

Maybe sit the next couple of rounds out, champ. After all, at the end of the day: it’s not for you.

—

David James Young is an Australian writer and podcaster. Send death threats to his Twitter, @DJYwrites.