Bros Before OS? How Her’s Samantha Is More Than A Manic Pixie Dreambot

"As its title suggests, this is a film in which a man learns it isn’t all about him."

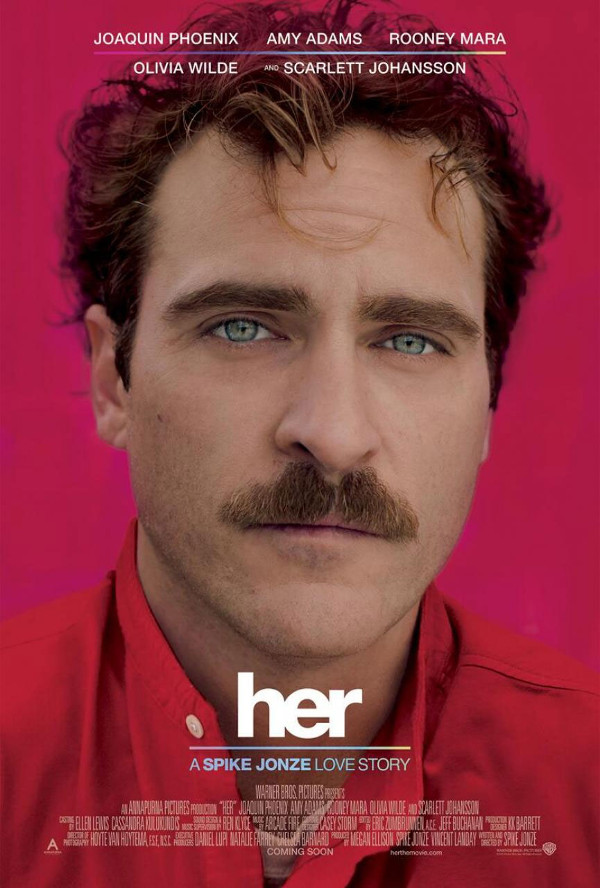

The poster for Spike Jonze’s new romantic drama is striking: Joaquin Phoenix’s face floating in winsome closeup against a rose-red background. He is clearly the protagonist. But the film’s called Her.

‘She’ is Samantha, an artificially intelligent, intuitive computer operating system, voiced kittenishly by Scarlett Johansson. Theodore Twombly (Phoenix), a sensitive copywriter still pining for his almost-ex-wife Catherine (Rooney Mara), purchases the OS and finds himself falling for the sassy, sympathetic new presence in his life.

It’s tempting to regard Her cynically as the ultimate expression of masculine solipsism. But as its title suggests, this is a film in which a man learns it isn’t all about him.

–

A Benign Technology

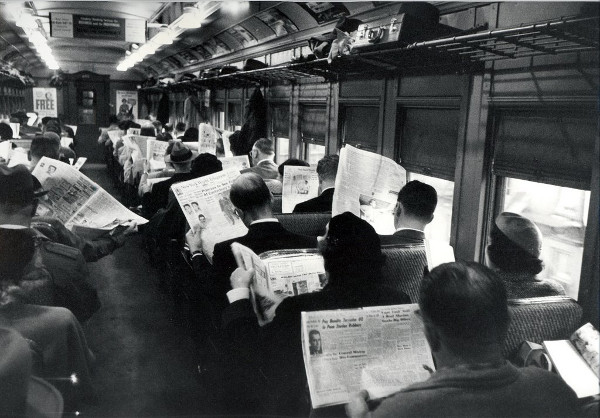

Cinema often dramatises the negative impact of technology, showing it dominating ordinary life in invasive ways. In film, as in real life, high-tech devices represent panoptical capitalism: they fill sightlines with pixels, monitor and record citizens’ every move, and entrench socioeconomic divisions.

Such dystopian fantasies reflect our anxiety that if we become over-reliant on these devices and software, we won’t just lose our intelligence but also our humanity, becoming corporate cyborgs — an anxiety we’re already seeing in the cultural ambivalence towards wearable technology such as Google Glass.

Neither the attachments nor the anxieties are especially new. University of Sydney sociologist Deborah Lupton has written extensively on our emotional relationships with technology; in a 1995 essay entitled ‘The Embodied Computer/User’, she reported that users describe their PCs as “friends”, “work companions” and even “lovers”.

In the film, Theodore works for a company called BeautifulHandwrittenLetters.com, ghostwriting heartfelt correspondences like a near-future Cyrano de Bergerac. Just as Theodore’s work comforts its recipients with an old-fashioned, personalised aesthetic, Her’s gorgeous, retro-futurist production and costume design — all high pants and moustaches — is reassuringly, tastefully wistful and melancholic. Like a smartphone ad, this sleek, sorbet-coloured world is charged with a promise of belonging and fulfilment.

The film’s benign tech differs from our own because it has dissolved seamlessly into everyday life. In this world, everything just works, freeing people to enjoy beaches, al fresco dining, and clean, swift public transport. I was sure there’d be a WALL-E-style dénouement in which Samantha crashes, corrupts or gets returned to her factory settings, but no.

Most machines are controlled by voice, although Theodore plays a holographic game by making absurd burrowing hand gestures, like a rodent. He talks to Samantha through a wireless earpiece; she sees through a smartphone resembling a cigarette case. But unlike us, he doesn’t cosset his phone in purpose-made cases, wallets and holsters; Theodore has to safety-pin his shirt pocket to make it small enough for Samantha’s camera-eye to peep out the top.

And while Samantha has complete access to Theodore’s digital life — and sometimes makes unilateral decisions based on what she finds there — there’s no suggestion she will abuse his trust by handing his data over to a third party. The altruistic intimacy of this OS/user relationship is the antithesis of Edward Snowden’s cautionary tales, or Mark Zuckerberg’s capitalist dream of completely transparent online sociality.

–

More Than A Manic Pixie Dreambot

In a cinematic culture saturated with macho characters asserting themselves upon the world through action, Her is refreshing because its hero’s journey is an interior, emotional one. And it’s moving because its characters are striving to identify what they want and need from relationships.

“Sometimes I think I’ve felt everything I’m ever gonna feel,” Theodore agonises to Samantha. “And from here on out, I’m not gonna feel anything new. Just lesser versions of what I’ve already felt.”

At this point, I cried — largely because of Phoenix’s tremendously tender, vulnerable performance. But from a feminist standpoint, it’s easy to despise Theodore.

Cinema is full of Manic Pixie Dream Girls: quirky, idealised soulmates who help angsty man-children heal their emotional wounds and teach them to savour life. Manic Pixie Dream Girls are like imaginary friends, or the daemon animal companions in Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials novels — they are really an extension of oneself. In Jungian psychoanalysis, men personify their repressed femininity as their anima.

Similarly, many human/AI relationship movies have a human protagonist bring an AI into consciousness through some quirky action — like Lisa in Weird Science, or Edgar in Electric Dreams. The AI then helps the humans kick social goals.

If we look at Samantha this way, she seems an egregious Dreambot because Theodore bought her. Let’s not forget that the word ‘robot’ comes from the Czech for ‘slave’. And in both real life and pop culture, artificial intelligence can have complex and dubious gender politics.

A chatterbot inspired Jonze to make the film, and one of the earliest chatterbot programs is named ‘ELIZA’ after Eliza Doolittle from George Bernard Shaw’s play Pygmalion — another character ‘brought to life’ by male tutelage. ELIZA was also programmed to interact with users like a therapist with a patient, much as Samantha behaves as Theodore’s confidante.

Samantha is also being widely compared to Siri, Apple’s virtual personal assistant. There’s certainly a suspicious preponderance of feminised, servile AIs, from Actroid, the robot designed as “a perfect secretary who smiles and flutters her eyelids”, to Rachael, the replicant secretary who doesn’t know she’s a replicant.

But Samantha cheerfully asserts herself; her first act is to choose her own name. She learns at her own exponential pace, expresses her own desires, and frets because she lives in the cloud, not in a body. She and Theodore strive to transcend the inescapably mediated nature of their love in ways that are valiant, heartening and unexpectedly sexy.

Their relationship isn’t unique. People everywhere, including Theodore’s friend and neighbour Amy (Amy Adams), are befriending and dating OSes. I really liked the way practically nobody finds this weird or antisocial. “We are only here briefly, and in this moment I want to allow myself joy,” Amy says. In one lovely moment, Theodore dozes off on the couch at Amy’s office and wakes to hear her chatting with her OS best friend with an unguarded warmth completely unlike her fretful conversations with Theodore.

I adored Her because it tells a story of technology using the DNA of a love affair: longing, flirtation, disappointment, delirious lust, contentment, jealousy, heartbreak and confusion. Theodore comes to a decidedly grown-up revelation: that while Samantha still loves him, she doesn’t belong to him, and he doesn’t even understand her. She’s writing her own code, and he’s just a few digits.

–

Her opens in cinemas nationally this Thursday.

–

Mel Campbell is a freelance journalist and cultural critic. She is the founding editor of online pop culture magazine The Enthusiast. Her debut book, Out of Shape: Debunking Myths about Fashion and Fit, is out now.