Here’s How A ‘World of Warcraft’ Pandemic Could Help Us Better Understand Coronavirus

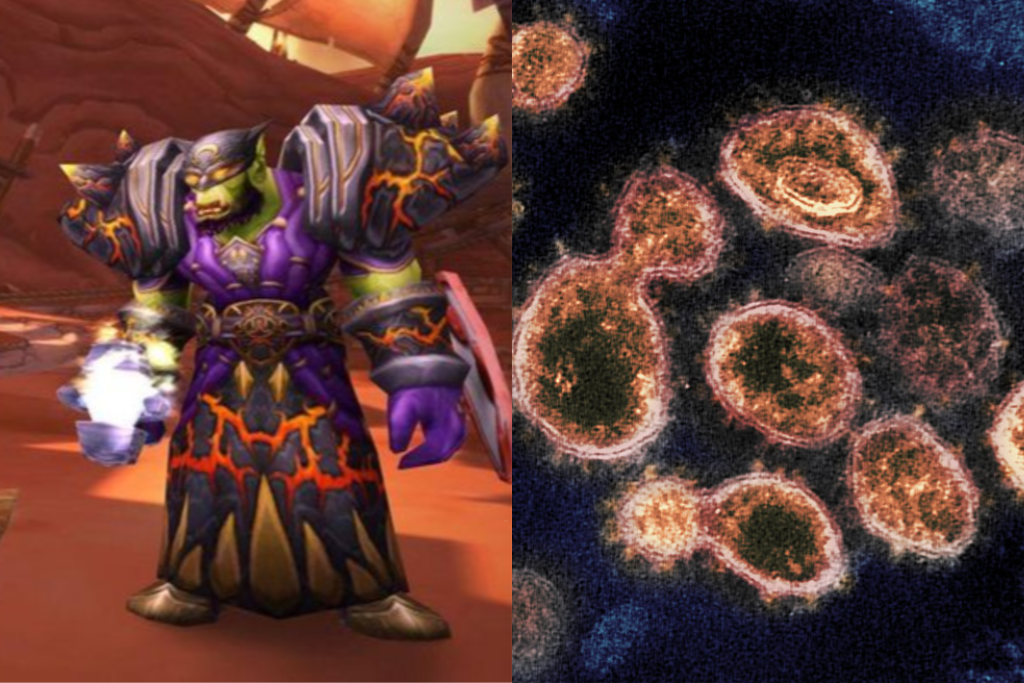

Scientists used the 'Corrupted Blood' bug as a model to predict and study the way that actual illnesses jump from carrier to carrier.

It’s safe to say that even now, during the outbreak of the coronavirus, most of us still don’t have a working knowledge of how viruses spread or how we might hope to contain them. Which makes this a perfect opportunity to examine the case of the ‘Corrupted Blood’ virus, a bug that gripped World of Warcraft some 14 years ago.

That might sound like a wild leap — from a real-life illness to a defect coded into one of the biggest multiplayer games of all time. But the ‘Corrupted Blood’ bug was so widespread, damaging, and fast-moving, that scientists have used it as a model to predict and study the way that actual illnesses jump from carrier to carrier.

But what is ‘Corrupted Blood’, and what can it tell us about coronavirus?

The Origins of Corrupted Blood

World of Warcraft is a sprawling, online multiplayer game which is constantly being updated with new missions and patches. Some of these are major expansions; some are minor additions.

It was a relatively minor update that kicked off the ‘Corrupted Blood’ pandemic. On September 13, 2005, patch 1.7.0 introduced a new raid — or, co-operative mission for all of you non-World of Warcraft players. Named Zul’Gurub, this skirmish deep into the heart of the Stranglethorn Vale saw players come up against a unique antagonist, the blood god Hakkar the Soulflayer.

Immensely powerful, Hakkar would cast a highly-contagious ‘debuff spell’ against all that faced him. This spell drained the health of players, doing a staggering 200-300 damage per second. That made it extremely dangerous for low-level players, and a threat even for those who had been playing the game for some time.

Like all MMORPGs, World of Warcraft is arranged around a difficulty curve, so that players only encounter threats that they are prepared to deal with. Thus, though the debuff spell was a significant challenge, it was designed only to be encountered by those strong enough to make it through Stranglethorn.

But there was a problem: developers had forgotten to close the loop on non-human animal characters.

Given coronavirus fears, more people should know about the Corrupted Blood bug in World of Warcraft that caused player chars to be infected with a killing debuff that soon spread to other players

Epidemiologists actually STUDIED this to see how ppl would react to an epidemic irl

— Rin (buy WICKED AS YOU WISH 3/3/20) (@RinChupeco) March 7, 2020

Basically, the debuff spell would eventually kill all human characters who had it. But it would also infect their pets, the animals that they brought with them on a raid. These pets wouldn’t be killed by the disease, but would spread it, meaning that if they were summoned again anywhere else on the map, they would start infecting player characters.

Worse still, these pets would infect player characters in parts of the map frequented by low-level characters. Player reports from the time say that entire cities were filled with the bodies of dead players.

Panicking, some self-imposed quarantine measures, fleeing to the countryside and scattering normal operations of the game. But even these measures were largely unsuccessful, thanks to troll players actively working to spread the disease, and thanks to the way it halted normal proceedings of the game.

World of Warcraft is not an experience best enjoyed wandering around by yourself in a field, and so people either got to infecting others, or quit the game altogether.

Eventually, a month after the spread of the disease, Blizzard managed to stop the debuff spell through an update patch that made non-human animals immune. Finally, the spread was over.

What Does Corrupted Blood Tell Us About Coronavirus?

In the years after the Corrupted Blood pandemic, a number of researchers have commented on its similarity to the real-life spread of diseases like SARS and avian flu. As was the case with those two real-life pandemics, Corrupted Blood spread from remote areas into densely-populated cities, and was largely moved via non-human animal carriers.

In that way, Corrupted Blood was used as a kind of model test case for viral research. Particularly interesting to researchers was the ‘gawker’ phenomenon — the way in which non-infected players would travel to sites of infection to see what was up before leaving, thus spreading the disease with them. Some noted that this was similar to the behaviour of journalists in real-life epidemics, who mingle amongst others in cities, before spreading the disease with them.

Which is exactly what is happening now with coronavirus, with reporters from around the world travelling to disease sites, and frequently facing little — if any — quarantine regulations when they return to their home country.

Nina Fefferman, a medical researcher who wrote extensively about the game’s implications for real-life illness, also pointed out the way that ‘bad-faith’ carriers have the ability to spread the disease further. “These are my mice,” she said of the game’s players. “I want this to be my new experiment setup.”

Of course, there are differences between the game and the real-life spread of coronavirus — if nothing else, we can’t ‘hard reset’ or install a patch to eradicate our real-life disease. But it’s a fascinating look into how diseases spread, and what we can do to stop them.

Joseph Earp is a staff writer at Junkee. He tweets @Joseph_O_Earp.