How ‘Wallace And Gromit’ Became One Of The Most Lovable Cartoons Of All Time

We sat down with the creators at their new Australian exhibition.

One of my favourite things about Wallace and Gromit has always been that — relative to the pair’s intellect, optimism, and hard work — they were incredibly ordinary.

They happily changed jobs every episode, repurposing their mechanic genius for window-washing, baking, and rabbit-relocation. Wallace enjoyed platonic, but never long-lasting or romantic, relationships with a variety of people. And, according to Aardman Animations founders David Sproxton and Peter Lord, as archetypical British “underdogs” the characters are filthy as.

“We had a lovely conversation many years ago when we were making Curse of the Were-Rabbit, where [Dreamwork’s head Jeffrey] Katzenberg, said “why is Wallace’s van so rusty?” David tells Junkee. “And we all just sort of thought, how do you explain that, that cultural shift?”

“He expects them to have a brand new shiny chevrolet. But, as a Brit, he just paints up his old van with his new occupation,” he says. “And of course it’s an old rust bucket. That’s how it is in British Comedy.”

This vision of one working class everyman and one very good dog as mechanical geniuses is only one of Aardman’s many charms; charms which are on showcase right now at ACMI’s latest exhibition, Wallace & Gromit and Friends: The Magic of Aardman.

Originally curated by Paris-based entertainment museum Art Ludique-Le Musée celebrating the company’s 40th anniversary, the exhibition is equal parts nostalgia, humour, and spectacle. There’s the bizarre flying machine from Chicken Run, Gromit’s beloved vegetable garden from Cure of the Were-Rabbit, and a beautiful, five-metre-tall ship from their lesser-known but genuinely hilarious 2012 film The Pirates! Band of Misfits.

They’ve even got that evil, soulless penguin from The Wrong Trousers, Feathers McGraw, complete with terrifying dead eyes. I hate that penguin. With every inch of myself I hate it.

Complete with historic and often horrifying sketches, replicated workstations, and a DIY claymation studio, Wallace & Gromit and Friends is a genuinely impressive celebration of Aardman’s enormous film and TV work. It’s a loving testament to the company that’s almost single-handedly kept claymation going for over four decades.

Humble Beginnings

Founded by Lord and Sproxton as film students in 1972, Aardman’s earliest work included claymation sequences for Vision On, a BBC series for children with hearing impairments.

The pair then began professional productions after graduating and moving to Bristol in 1976, where they created the simple claymation man Morph for follow-up series Take Hart, as well as more adult content such as Conversation Pieces (1982), an animation of puppet characters set to real-life conversations, and Early Bird (1983), set during a radio station’s morning shift.

The most obvious question to a film school hack like me is “how did you have the patience for claymation”, but the pair agree there was never really any other choice. “Funny thing is: it’s rather simple, which is funny, but that was the main attraction,” Peter says. “Before, we had a brief flirtation with drawn animation where you hand-draw every frame, and that seemed quite mechanical, and difficult and slow.”

“Clay animation, when we started, just proved to be instinctive and relatively easy. And it still is. There’s a workshop [at ACMI] for kids to have a go, and the fact is that anyone can take a lump of clay and bring it to life in some shape or form, without any practice at all. To do it simply is very easy; to do it well takes a lot of time and effort.”

It was the relatively simple adventures of Morph, who went on to star in a 26-part five-minute BBC series in 1981, that garnered the attention of Wallace and Gromit creator Nick Park.

Park met the pair while making A Grand Day Out as a student at the National Film and Television School, going on to join Aardman full-time in 1985 and premiere the student film in 1989. It went on to be nominated for an Oscar in 1990, losing out to Park’s other production that year, the animal mockumentary Creature Comforts.

“On Grand Day Out, Nick worked almost as a solo-machine, he did almost everything on that thing and it took him forever,” David says. “The [23-minute] film in the end took about seven years to make, and the characters were kind of prototypes; if you look at Wallace in Grand Day Out and Wallace in Curse of Were-Rabbit, it’d be like Mickey Mouse.”

Claymation Powerhouse

Since those early days, Aardman has basically exploded, not only producing a tonne of mini-projects, two Creature Comfort series, and four more Wallace and Gromit films — including the feature-length Were-Rabbit — but also expanding into the groundbreaking Chicken Run (2000), spin-off series such as Shaun The Sheep (2007), the CGI-driven Flushed Away (2006), and the upcoming Early Man (2018).

And seriously, if you haven’t seen The Pirates! yet, do yourselves a favour and check it out. Very Sad Charles Darwin and Evil Swashbuckling Queen Victoria do not disappoint.

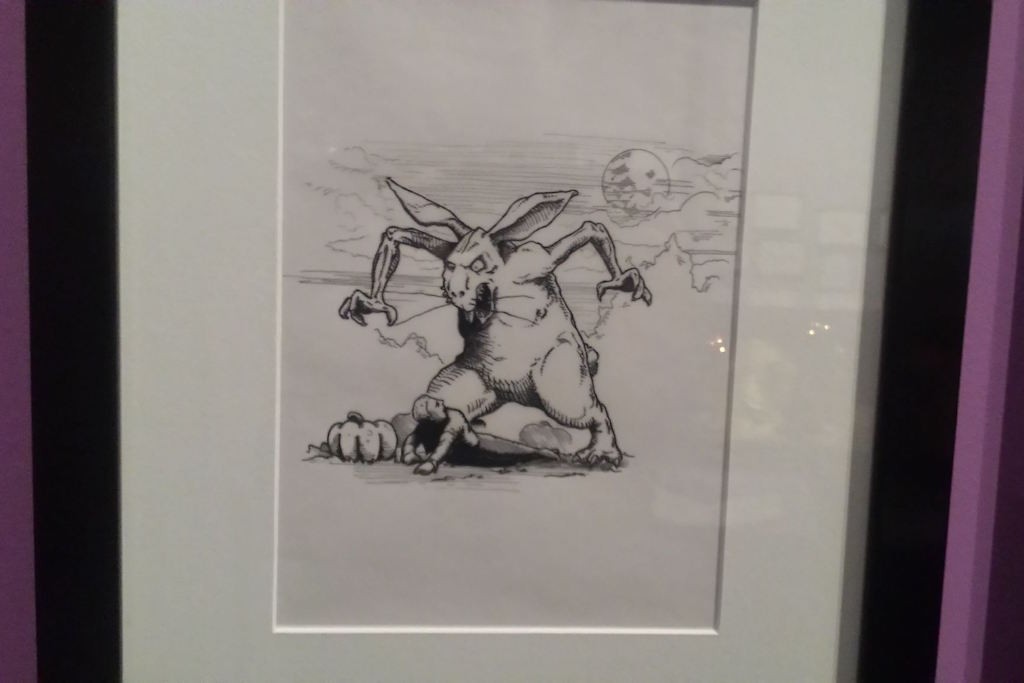

Words can’t do justice to how bloody dense this new exhibition is. There are dissected figurines, in-film joke posters, that aforementioned workstation, complete with original designs and sketchbooks. There’s a Were-Rabbit display that features horrific early designs that will haunt your dreams.

This was meant to be a children’s movie :(

While all of Aardman’s projects have varied in scope, style and creative partners, they’ve all managed to retain the studio’s exaggerated, warm and somehow grounded sensibilities. If David and Peter’s enthusiasm is anything to go by, they’ve also been a riot to film.

“It is fun y’know, I joke at the expense of other studios. I say Pixar [is full of] very nice people, very nice offices, but that’s because the work is kinda dull. All they’re doing is sitting at computers all day,” Peter half-jokes. “Whereas at our place, it’s physical, you’re up on your hind legs, you’re moving, stretching, working with metal, and paint, and physical 3D things.”

“In terms of the animators, it’s a performance,” David adds. “I mean it’s planned and sort of rehearsed, as you would do with a film or a play, but the animators are animating frames in what we call a linear, progressive approach. As opposed to CG or 2D, where you might go frame one, frame 24, back to frame 12, frame 26; you can’t do that with stop frames. The animators are our actors, and there’s quite a lot of spontaneity in their performance.”

A Lasting Impact

Finally, it’d be remiss not to mention the studio’s obvious impact on the next generation of animators. Namely Oscar-winner Adam Elliot, whose Harvey Krumpet figurine is just upstairs at ACMI.

And rather than worry about the potential death of claymation in the face of emerging, virtual reality technology, the pair are excited to see how the two artforms complement each other.

“We were inspired by [‘Dynamation’ creator] Ray Harryhausen and his wonderful worlds,” David says. “It’s lovely to see that kind of passing on and moving forward. The other thing is just watching these screens [at ACMI]. The technology we have today, the digital technology and all that it can do, means that you can create the most extraordinary worlds and do the most extraordinary things.”

“In the wonderfully crafted nature of stop-frame, you can do things which 10 or 15 years ago would have almost been impossible. The pirate ship sits on what looks like very photo-realistic water; the ship’s a model as we can see here, but the water that it sits on is entirely CG, so you’ve got the best of both worlds. It’s a very exciting world to be in because the toolset is just phenomenally useful.”

PS. Yeah I had a go at ACMI’s claymation workshop. It was just a juvenile attempt at mooning the camera, and yeah, sure, I chickened out and ran off early because the very kind assistant kept asking if I needed help and I almost passed out from constant embarrassment. But because I am now safe behind a computer screen, go on. Look upon my works, ya’ll mighty, and do NOT judge me!!

–

Wallace & Gromit and Friends is on at ACMI in Melbourne until October 29.

–

Images: Charlie Kinross/ACMI and Chris Woods.

–

Chris Woods is a Melbourne-based freelance journalist.