“They Always Felt Like A Dream”: Shaun Tan’s Made You A Very Unconventional Book Of Fairytales

One of Australia's favourite illustrators has created some serious magic with the stories of the Brothers Grimm.

One of Australia’s most celebrated writer/illustrators, Shaun Tan has captured the confusion and alienation of youth in picture books like Rules of Summer, Tales From Outer Suburbia, and The Lost Thing. He’s worked as a concept artist for Pixar and other film studios, and won an Oscar for his short film adaptation of The Lost Thing, and his other groundbreaking works such as The Red Tree — a surreal story about depression — have redrawn the lines for what Australian children’s books can address.

Now, he’s using his probing eye for eerie ambiguity and otherworldly vistas to reinterpret the unmoored dream world of Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm’s enduring fairytales.

–

A Book With Shadows Instead Of Characters

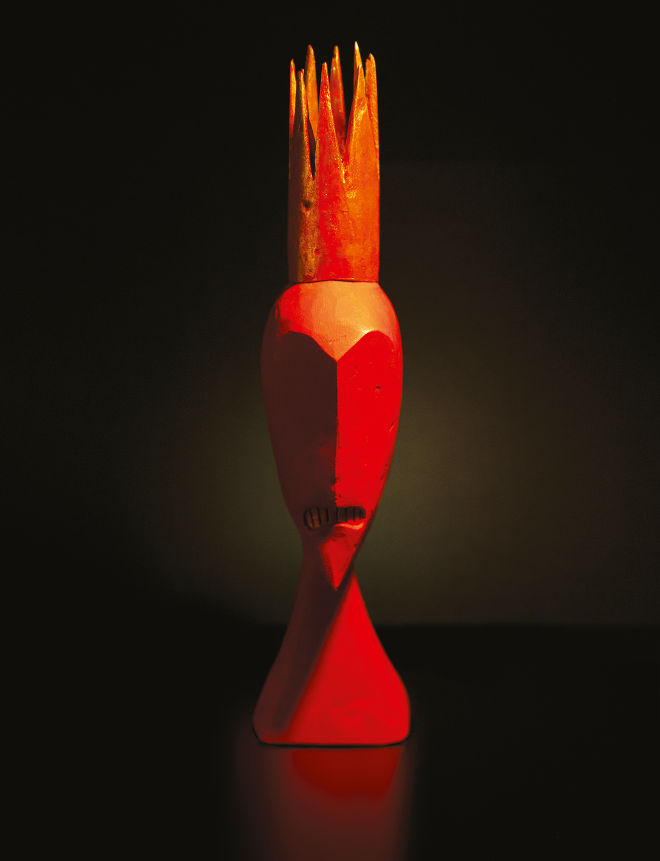

Tan’s new work, The Singing Bones, portrays moments from 75 of these classic tales; but it’s not really a story book, and it’s not illustrated in Tan’s usual way. Instead, it catalogues 75 clay sculptures that Tan created, painted, arranged, and photographed, each accompanied by a laconic snippet of the story. Rendering each of the tale’s spirit or subtext visually rather than trying to encapsulate the plot, each piece is a stunning act of distillation that recasts even the most archetypal of stories.

“I’ve always wanted to do sculptural works, but never found the correct avenue for it,” Tan says. “It’s quite labour-intensive and not suitable for certain deadlines.”

The project originated from a commission to illustrate the cover of a German edition of Brothers Grimm retellings by His Dark Materials author Philip Pullman. Tan convinced the publisher to not only let him illustrate the book itself, but to do it with a series of 50 sculptures. Then he made another 25 on his own. Part of the inspiration was Pullman’s comment that the Grimm stories are often best left unillustrated because they don’t benefit from elaborate visual depiction.

“That set up a creative problem that I enjoy,” Tan says. “And I agree with him. There’s not a lot of description or embellishment, and illustration is often all about those things.”

Tan also suggests that illustrating the stories can diminish their universal feel. “The scenes become localised in a Germanic forest, whereas for me they always felt like a dream,” he says. “The moment you start drawing the characters — putting eyes and noses and mouths on them — you lose that dream-like vagueness. As Pullman says, there are no real characters in the stories. They’re like shadows.”

True to this idea, Tan’s figures are more open and symbolic, often favouring blankness over specificity. Many of the sculptures are left unpainted or only minimally coloured, looking as if the life has been drained from them — all too appropriate for these murderous tales. That makes it that much more surprising, though, when you turn the page to find a piece saturated and enlivened with brilliant colour.

“Colour for me is a very emotional layer that you put on after you’ve conceived the form,” Tan says. “In most of my work, colour is not necessary.” He points out how the lack of description in the Grimm tales extends to colour too; the stories only reference colour when absolutely necessary, as when something is made of gold.

–

The Enduring Magic Of The Fairytale

As common as these stories are in popular culture — from classic Disney movies to modern remakes like Grimm and Once Upon a Time — Tan doesn’t present anything approaching a familiar depiction. Drawing inspiration from Inuit sculpture and Central American folk art (with several pieces referencing the cheerful skulls and gaudy hues associated with Mexico’s Day of the Dead celebration), he instead chooses to bring out the inherent strangeness of the stories and avoid the most obvious scenes.

As a result of this, Rapunzel’s hair drapes all the way down the tower of her imprisoning, but Tan merges her featureless face with the tower itself. Hansel and Gretel eat from a candied house, but it’s an incredibly subdued and uncanny depiction of the house. Cinderella is depicted only as a sad golden face lodged at the foot of a soot-capped chimney. And, rather than focusing on Snow White, Tan instead shows the Queen frozen in red-faced rage, framed by a pointy chin and wickedly jagged crown.

The challenge for him throughout was not only deciding which moment of a story to portray, but how and from what angle.

With the pieces going on temporary exhibition in Melbourne this week, they’ll be free of the set perspective they have in the book. And that’s something Tan is fine with. “I think what they lose in that stage-y atmosphere, they gain in dimensionality,” he says. “They suddenly become actual objects rather than representations of objects.”

One of the most striking pieces depicts Rumpelstiltskin in full impish glory — a bright reddish orange all over with his oversized mouth gaping. But while some readers might interpret him as jovial, to Tan it’s all about the creature’s rage: “He’s so angry, like a little ball of fury”. That ambiguity is intentional: characters are shown with huge smiles in even the bleakest scenes, and many pieces mischievously blur the lines between happy, sad, and angry. The original stories are much the same, always choosing the surreal over the certain.

“Maybe that’s why they’ve survived for so long,” says Tan. “Even when they’re very sinister, there’s an absurdity to them. They’re obviously fun to tell. If they were too dark, they’d be quite painful to recall.” Speaking specifically about Rumpelstiltskin, Tan thinks he remains popular precisely because his motivations are left unclear. Laughing, he adds, “Today you’d probably say he’s bipolar”.

–

The Singing Bones is out now. The exhibition launches 6pm this Thursday at No Vacancy Gallery in Melbourne.

–

Doug Wallen is Editor of Mess + Noise and Music Editor of The Big Issue. He also writes for Rolling Stone, TheVine, FasterLouder and The Thousands.