The Youth Will Inherit The Apocalypse: Why ‘The 100’ Is The Ultimate Millennial Fantasy

Rich, entitled old people ruin the Earth, then leave their kids to clean up the mess. Just like in real life!

If I know anything, it’s that kids have got to do it for themselves – or, at least, that’s what young adult literature has taught me. It’s a venerable trope that stretches all the way back to Enid Blyton’s plucky child detectives: stories about kids forced to do what the crusty old people can’t, which is usually saving the day. Often it’s a difficult stretch – where the hell are the parents? Why haven’t they noticed that their daughter can turn into a puddle of liquid metal? Why aren’t the police solving this murder?

So it’s no surprise that TV’s The 100 features an intrepid band of hot youths who hold the fate of the planet in their hands – but instead of fighting off werewolves or Cornish smugglers, the perfect-haired teens of The 100 battle a far more insidious enemy: Baby Boomers.

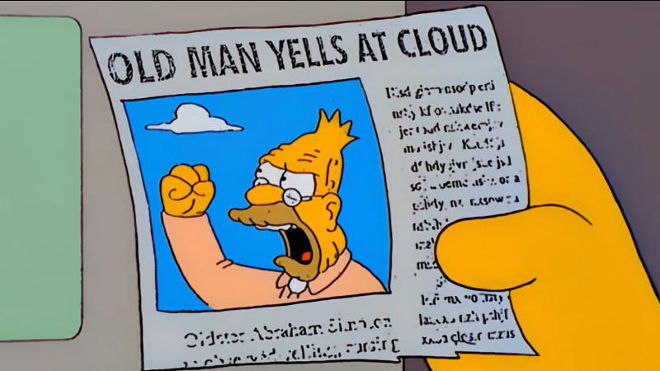

Pure evil.

The best use of young people dominating TV shows is when the age of their characters are the driving feature of the story – Buffy the Vampire Slayer is an elaborate metaphor for how hellish high school is, which would have been unfeasible without a cast of semi-teens. The show could easily be pitched with older people – the greater plot of Buffy really has nothing to do with high school and teen issues, as it’s generally about vampires trying to destroy the world – but its teen protagonist is what creates the drama. The same can be said of Pretty Little Liars – as a murder mystery, it’s frustrating and lacking in rigour. Add in high school politics and it’s somehow fascinating.

Where The 100 truly excels is in the troubled relationship between the youth and the older generation, manifesting as both statement and battle between generations. The 100’s premise is that 97 years ago the world finally bombed itself into oblivion, and the last remnants of the human race were left up in space on a cobbled together super space-station. Because of the severity of living conditions and the scarcity of resources, any crime committed on the station is immediately punishable by jettisoning the offender into cold space. Exceptions are made for anyone under the age of eighteen, who is locked in prison until they reach their majority.

The plot begins when the people in charge discover that they don’t have enough air, and decide to get rid of the hundred juvenile offenders they’re holding by sending them down to Earth, justifying it by claiming it’s a research mission to see if the Earth is habitable yet. Considering they’re pretty sure the earth is an irradiated wasteland, this is basically a fancier way of killing them. It’s not hard to see the metaphor here – the older generation, the people in charge of the station, are literally stealing air from the youth. The catch, of course, is that earth isn’t a nuclear pit, and is actually doing fine. Those plucky teens!

–

Boomers Ruin Everything: The 100‘s Familiar Premise

The 100‘s premise brings to mind a recent article in The Monthly by Richard Cooke, The Boomer Supremacy. In it, he describes the prevailing attitude among the Baby Boomer generation that Gen Y have been excluded from the property market – not because of an unfair monopoly perpetuated by their generation, but because of a moral failure of our own making. Cooke says:

“In 1975, the average Sydney homebuyer took three years to save their deposit, and the average home cost four times the annual income. In 2015, the average Sydney homebuyer took nine years to save their deposit, and the average home cost 12 times the annual income. But read the comments section under any article on property prices, and it will be full of unsolicited advice from people who bought a home 40 years ago. It wasn’t easy for them either, but they made sacrifices – they didn’t eat in restaurants, they didn’t go on holidays, they didn’t go out. Occasionally someone will advocate living ‘away from the city’, and it will turn out they bought their first home next to the beach.”

Our moral failure is basically being born into a property market – or spaceship – dominated by an entrenched generation who are unwilling to make space (pun intended) and then being punished for being unable to fit into that space. Certainly sounds like stealing oxygen to me. Unfortunately for us Millenials, we don’t have anywhere to be jettisoned to. Maybe we should go to space? It’s probably cheaper than inner city living.

Science and speculative fiction have long been a place to reflect human anxiety, and make dire predictions based on that anxiety. Books like 1984 and Brave New World expressed fears about how surveillance and state control might negatively impact society. Kurt Vonnegut famously feared mankind’s dependence and obsession on technology in books like Player Piano, The Sirens of Titan and Cat’s Cradle. In the aftermath of the atomic bombs being dropped on Japan, this anxiety about science and weaponry was commonplace.

The 100 continues this tradition of excellent speculative fiction by reflecting the anxiety that Millennials have about inheriting a garbage world that has been completely fucked over. Issues like climate change and mining, war and terrorism have been major global concerns for the majority of our lives – and seem impossible to solve, due to the intransigent greed from the people in charge. To a degree, all the characters in The 100 reflect this concern – they all live with the consequences of the previous generation bombing the earth into inhabitability.

–

Sci-Fi As A Reflection Of Real Life

In the show itself, the drama of this anxiety is played out on a personal scale. After finding out that their ‘let’s send our children into a radioactive wasteland’ gamble has paid off, the parents up in the space station decide to relocate back to Earth. In the meantime, the cool kids with great hair have been doing a fairly excellent job of surviving, including negotiating a truce with the violent yet sexy natives (I can’t be bothered explaining why there are natives who survived the nuclear apocalypse) and fighting off some cannibals. The parents, of course, come down and immediately attempt to take control, screwing over every attempt the teens have made at peace and sustainability.

This is particularly played out in the relationship between Clarke (Neighbours alumnus Eliza Taylor) and her mother Abby. Clarke becomes the unofficial leader of the teens and official delegate to the Grounders (apocalypse-chic natives), while Abby takes up the mantle of Chancellor of the space-people. The two of them represent both their generations and clash over different ways of thinking. Abby is at times replaced by different Chancellors, each representing a different form of repressive governance, with the current Chancellor promoting a xenophobic platform which plays on fear and highlights an ‘us and them’ mentality. At no point in the current three-season arc has the tension between generations ever been resolved.

Science fiction always seems like a hyperbolic reaction to current events, a creative slippery-slope theory that takes a regular, everyday fear and projects it all the way into space and apocalypse scenarios and sultry robots. The 100 is no exception to this – the arc of Season Two revolves around a bunker full of old white people who have survived the nuclear fallout in a bunker called Mount Weather, surrounded by priceless works of art and classical music and old-timey outfits. They’re a perfect metaphor for the rich and privileged parts of society, the ones that are invested in the status quo, and happy to support things like lock-out laws and increased investment in coal mining. Also, these bunker-folk literally survive by stealing blood from the young. Mmm, that’s good symbolism.

Thing is, the intergenerational tension that The 100 relies upon isn’t a fantasy. It’s something that’s happening now, that we live with in one form or another every day. I’m not saying that the next step is actually going to involve launching Gen Z into space, but we have a thousand actual disasters literally happening around us, from the melting ice caps to the hottest summers in memory. We don’t have to stretch our imagination too far to imagine everything going to shit. All we can hope is that our hair is as beautiful as Bob Morley’s when the apocalypse comes.

–

Patrick Lenton is a writer of theatre and fiction. He blogs at The Spontaneity Review and tweets inanity from @patricklenton.