Sydney’s Lockout And The Moral Panic We Need To Disengage From

NSW's proposed new licensing and lockout laws are the result of a media-initiated moral panic, and they won't deliver the results they promise.

Societies appear to be subject, every now and then, to periods of moral panic. A condition, episode, person or group of persons emerges to become defined as a threat to societal values and interests; its nature is presented in a stylized and stereotypical fashion by the mass media; the moral barricades are manned by editors, bishops, politicians and other right-thinking people; socially accredited experts pronounce their diagnoses and solutions; ways of coping are evolved or (more often) resorted to; the condition then disappears, submerges or deteriorates and becomes more visible. Sometimes the object of the panic is quite novel and at other times it is something which has been in existence long enough, but suddenly appears in the limelight. Sometimes the panic passes over and is forgotten, except in folklore and collective memory; at other times it has more serious and long-lasting repercussions and might produce such changes … in legal and social policy or even in the way the society conceives itself.

—Stanley Cohen (1972), Folk Devils And Moral Panics

The moral panic appears to us to be one of the principal forms of ideological consciousness by means of which a “silent minority” is won over to the support of increasingly coercive measures on the part of the state, and lends its legitimacy to a “more than usual” exercise of control.

—Stuart Hall et al. (1978), Policing The Crisis

–

This summer, Sydney has been experiencing a media-initiated moral panic over “alcohol-fuelled violence”, very much fitting what the late criminologist Stanley Cohen describe in his classic account from 1972.

Slightly unusually, it has been the liberal Sydney Morning Herald (and its Sunday edition, The Sun-Herald) leading the charge, with barely a day going by without another lurid front-page story on the issue. The paper, which last year went tabloid, seems to have decided to employ a campaigning style appropriate to its new format. Also unusually, the centre-Left ALP has tried to use the campaign against Barry O’Farrell’s Coalition state government, and O’Farrell has been pilloried for not instituting immediate tough measures to stop the violence.

After a period of silence, O’Farrell re-emerged on Tuesday morning with a sweeping set of new laws (the government’s factsheet here), including mandatory minimum sentences for people who kill others with one punch while intoxicated (a harsher penalty than if you do the same thing while sober!), and multiple restrictions on alcohol sales and service in a newly demarcated Sydney CBD zone.

I’ll leave it to others to sift through the multiple inconsistencies and hypocrisies in the new laws: how they will likely lead to increased criminalisation and incarceration of Aboriginal and homeless drinkers; how they will most likely move problems rather than fix them; how, as Lord Mayor Clover Moore argues, they could produce new flashpoints of violence with a “3am swill” effect; how some of the laws are really only about increasing the powers of the police to deal harshly with anyone they don’t like; and how certain sites are conveniently exempted to protect current and future casino operators, major hotel and tourist businesses — and so on.

It’s the moral panic that’s been the clear winner this week. As per Cohen’s schema, a “folk devil” has been identified in the shape of young men out to have a good time by drinking in one of the city’s nightlife hubs. Following Cohen, this folk devil is then scrutinised from a variety of viewpoints, with notables and experts pontificating about the deeper causes of the psychological, moral or social malaise he represents. To get a taste of the mishmash of colourful explanatory frameworks being bandied about in recent weeks, read this article by Peter Munro on “What makes one man attack another?”, from which I have drawn some choice quotes:

An unchecked primal urge … “These guys are just fuelled up with testosterone” … “It’s like one primate thumping another, or one intoxicated primate thumping another” … “It’s very primitive and you see it played out on the … streets” … Some young men seeking their place in the world — competing for partners and social status — lack suitable social structures or mentors to restrain their primal urges. … “We know that young people who are on the pathway to violent criminal careers typically come from broken homes, poverty, marginalised neighbourhoods and deviant friendships” … They develop a “twisted view of masculinity … They look for easy victims to display their status, their extreme machismo” … “Action movies, a sporting culture very much focused on dominance and win-at-all-costs, video games, violent internet porn”

Well, you get the idea. At least Munro didn’t go as far as Elizabeth Farrelly, who linked drunken violence to the trend for Ned Kelly-style beards. If you can bear more of this kind of thing, the Herald has a section full of it.

Facts, Schmacts

Tucked away in Munro’s grab bag is an important fact: that “alcohol-related assaults across NSW have fallen more than 20% since 2008”. But such facts are little more than a speed hump in the way of a good-going panic. This is because moral panics require unwarranted generalisations based on anecdotes and particular instances, and avoid a balanced and rational account of the totality and complexity of the problem they are allegedly addressing.

The SMH’s January 2 editorial didn’t hesitate to draw out the lesson, and the class undertones are hard to miss: “A culture of self-indulgent thuggishness is being incubated, primarily in broken families, and fuelled by alcohol, drugs and the normalisation of violence in popular culture.”

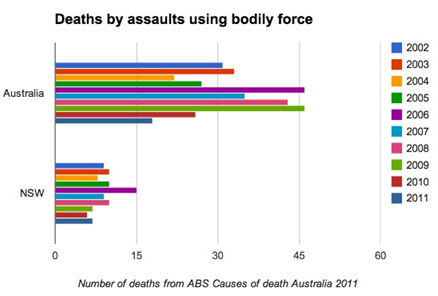

But peruse the most reliable data about alcohol and assaults — such as the gold-standard ABS survey of personal safety and violence — and you’ll find that most forms of interpersonal violence (including those involving alcohol) have been on the decline for two decades. Among other ABS data is the reality that “deaths from assault using bodily force” in NSW have been steady, or perhaps even trending down over the last decade (see the graph from Richard Farmer’s blog, below). Or you can read more balanced overviews — like this one by Don Weatherburn (head of the NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research, and hardly a bleeding heart) — to understand the decrease in alcohol-related reported assaults and emergency department visits, as well as the difficulties involved in accurately pinpointing trends. The NSW data has been laid out in graphical form in this good report from The Guardian. Look hard enough, and you can even discover that problem drinking in Australia has been declining for a while now, even among young people — despite the repeated claims by some public health campaigners that there is an urgent crisis, which have fed popular beliefs in its existence.

To our self-proclaimed moral guardians, who are whipping themselves into frenzies over the need for the state to act right now, such hard information is irrelevant or a distraction.

–

So What Should We Be Doing?

People have asked me what sensible measures I think can be taken to curb drunken violence; measures that progressives could put forward to shift the current debate. My view, however, is that this is not a real debate, and so there is nothing worthwhile to be engaged with or shifted.

When you have senior police officers wanting to move the focus of police from ensuring publican compliance with the RSA (an evidence-based policy) to “preventing violent incidents” on the streets (which has a lousy evidence-base, because police almost always intervene after the fact), you realise that “evidence” about “sensible measures that work” is not really the name of the game. One look at the general outline of what the SMH and others are demanding should indicate that the “solutions” being sought involve widespread state control over young people drinking and having fun, on the basis that very many people who never have and never will become violent when drunk need to have their freedoms taken away in order to prevent what are relatively rare actions by a small minority.

The state versus society

Simple measures, such as improved all-night public transport services (an easy way to prevent all-too-frequent flashpoints where frustrations over getting home boil over), barely register on the public radar, while exemplary sentencing, limitation of opening hours, lockouts, jacking up the price of alcohol and (I could barely believe it until I read it) renaming assaults to be called “cowards’ punches” are demanded as ready-made solutions. Out of all the unambiguously positive measures possible, O’Farrell has delivered only a free bus service out of Kings Cross on weekends, without addressing the parlous state of Sydney’s transport beyond that small area.

The key point here is that the state is not being expected to improve social conditions; rather it is being called on as part of a campaign to more closely control its citizens (their behaviour, their morals and, in this case, even how they talk about violence). In this moral panic, the fact that such controls rarely fix the problem is secondary.

As The Piping Shrike points out in passing, this kind of posturing reflects expectations that the state will solve a social malady, when in fact the state is congenitally incapable of solving such problems. At most, states might administer social ills differently — too often via an increase in repressive powers, which only shifts the problem and creates new social difficulties. This is exactly what we are seeing in O’Farrell’s response.

The reality is that a quick fix for drunken violence is an unrealistic expectation while existing social relations remain in place. This is not to diminish the frustration of health workers at the front line of drunken violence and its consequences, nor the disappointment of progressive “harm minimisation” advocates, that their suggestions have been ignored for years. But in a moral panic, only one side of the solution ever gets taken up with any enthusiasm — not more funding for health, but more funding for police to crack down on revellers; not the liberal harm-reduction policies, but the ones that involve effective prohibition and tight social control.

The only useful progressive response, then, is to start with the recognition that there is nothing in this moral panic for progressives. Moreover, the very premises on which the panic rests need to be rejected precisely because it takes real-world suffering by individuals and their families, and turns it into a general demand for greater control by the state over its citizens (a demand, furthermore, that cannot deliver the results promised of it).

Perhaps more controversially, I think progressives should challenge the stereotype of the “folk devil” being peddled by media and politicians, and defend the right of young men to drink alcohol and party. It is the dangerous fantasy of paternalistic state control over undesirable social behaviours by undesirable social elements that is at the centre of this moral panic.

–

This is an edited and updated version of a post at Left Flank blog.

–

Tad Tietze is a Sydney psychiatrist who co-runs the blog Left Flank. He’s written for Overland, The Guardian, and The Drum Opinion, as well as music reviews for Resident Advisor. He was co-editor (with Elizabeth Humphrys & Guy Rundle) of On Utøya: Anders Breivik, right terror, racism and Europe. He tweets as @Dr_Tad.

Image via Getty.