25 Years On, Melina Marchetta Tells Us Everything You Want To Know About ‘Looking For Alibrandi’

We talk smart girls, John Barton, and sex with Jacob Coote.

Spoilers for Looking for Alibrandi (Can you just read it now? Jeez).

This post discusses suicide.

—

It’s not an exaggeration to say that Looking for Alibrandi is woven into the psyche of a generation of Australians.

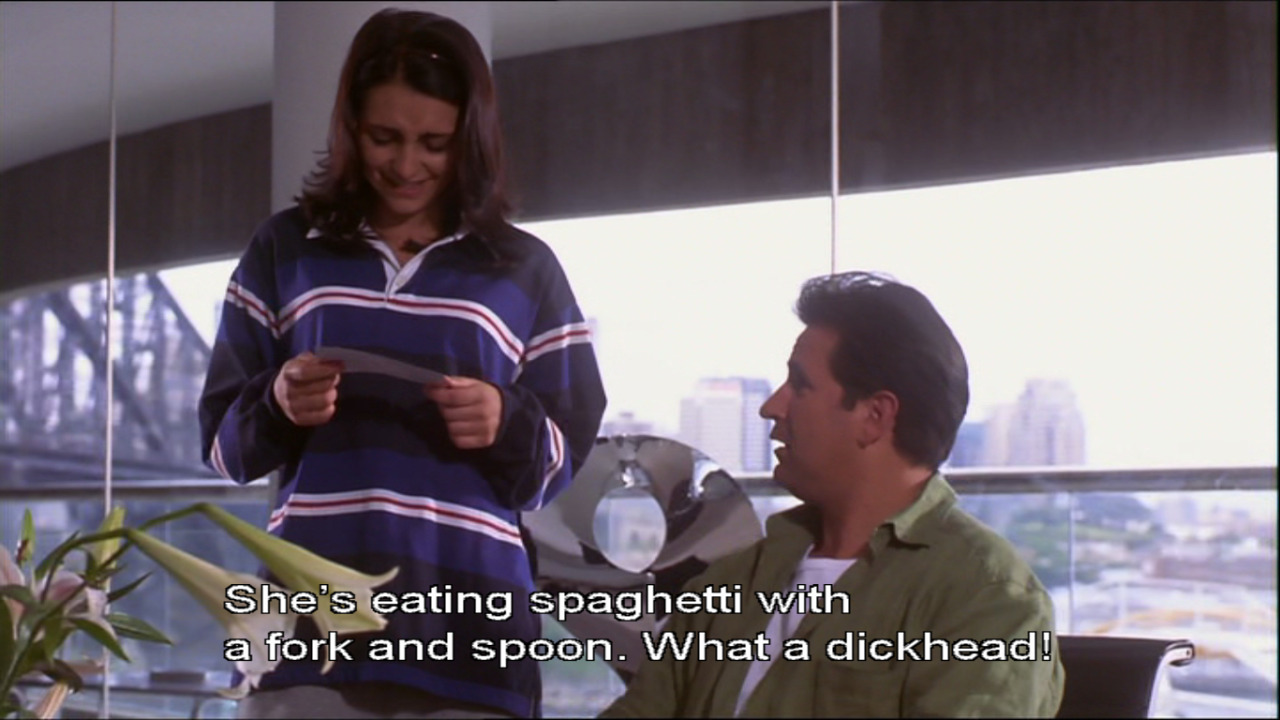

Melina Marchetta’s debut novel, which was released in 1992 and for which she wrote a film adaptation in 2000, still feels like a revelatory representation of Australian migrant stories, class, suicide, the struggle of being an outspoken and angry teen girl in a heavy Catholic school blazer and, of course, panels vans.

This year Marchetta is appearing as an ambassador at the Emerging Writers’ Festival (“I felt very nurtured in the early days by writers such as John Marsden and Isobelle Carmody and I’ve always found it important to follow their example”) and celebrating the 25th anniversary of Looking For Alibrandi.

She talked to us about coming to terms with John Barton’s death, the trouble with being the loud girl in school and Jacob Coote’s sex drive.

Junkee: Just by the by, Looking for Alibrandi and Saving Francesca mean a lot to me so I’m very excited to be talking with you.

Melina Marchetta: Oh, thank you! That’s lovely.

How long were you thinking about Looking for Alibrandi before you wrote it? Did you always know you wanted to tell this story?

I do remember when I was about 17 or 18 I was writing a story about a girl named Genevieve and she lived down in Kiama (NSW) with her single mum, and she meets her Italian dad for the first time. The thing with that is that I had never lived in Kiama or in a coastal town before, I had always lived in Sydney. So, obviously it was a bit ridiculous. But then when I picked it up again, what did remain was an Italian girl, but this time her mum was Italian as well, growing up without a father. But I moved her to Sydney because that’s where I was born and where I’ve lived all my life. So it was that familiarity that I think changed everything for me.

“There’s a freedom these days with identity.”

What I remember is all about connections. Everyone had told me all my life when I went to Italy for the first time it would click for me where I belonged. I remember going to Italy when I was 19 and that didn’t happen. But what did happen is that I got to talk to my great aunts and everyone who was back in Sicily and they were telling us stories about what happened when my family left Sicily back in the ’50s and the despair and the weeping, you know?

So it was kind of all of their stories that made me come back and want to write this novel. So I think that the origins would have been when I was around 20 years old. It was in my head for quite a long time before I published it at 27.

My parents are Irish immigrants and I felt kind of guilty that when I went to Ireland for the first time I didn’t experience this great cultural epiphany.

Yeah. I still had a great sense of belonging to an Italian family. But it was more of that question you’re constantly asked about, what country did you belong to. Now I feel like — obviously I’m Australian — but I like when I watch my nephews who are half Irish and half Italian, they don’t seem to have a problem with melting all these identities. There’s a freedom these days with identity, but back in my day I felt that you had to identify with a specific culture.

Why was depicting that second-generation migrant experience so important to you?

It’s still important to me. I think it’s always about this idea that there’s a dominant culture in this country and [migrants] are still trying to find their voice as someone who doesn’t belong to the dominant culture. I think that books, especially YA novels, have done a great job of that.

I don’t think that film and television have done a great job. When different cultures are shown on TV they’re often the villains, or they’ve done something wrong. I find that disturbing. I just think that diversity is such an exciting thing and it stops people becoming stagnant about ideas. I find that I’m not interested in a monoculture.

Josie Alibrandi is very ambitious and competitive, which is something I saw in myself and in my friends in high school but rarely saw in books and pop culture. Why was that aspect of her character important to you?

Firstly I needed it as a plot device because she would have never have gone to that school if she wasn’t on a scholarship. When people ask me how much I’m like Josie, I always say that she’s a lot smarter than I am and I’m a lot nicer than she is.

Josie is like my younger sister — she was the debater, she was very clever. I always found that outspoken, clever girls got into trouble a lot more for being outspoken and clever. It made me think, what is it that makes us shut women down? Back then it wasn’t celebrated as much. It was really important that Josie was the way she is, because it was her ambition and her voice that gets her into trouble a lot of the time.

Alibrandi didn’t condescend to its audience, it was very frank about sex and school, money and class. Have you noticed a shift in the way that stories about teenage girls are written about and received now?

Oh I definitely think so, for example books like Royal Blue and particularly YA in this country. Specifically girl’s sexuality, especially teenage girls, back in the day there was a stigma. You were called names if you in any way expressed a sexual desire. I actually like that these days writers are exploring teen sexuality.

That was a tricky thing for me back then. It’s not that I wanted to avoid it — I just didn’t think someone like Jacob Coote, not that he wouldn’t understand, but he wouldn’t be thinking that he and Josie wouldn’t have sex. That would be something that he might not have expected but that he would have wanted, so I just had to really explore how these two characters were different in the way they saw the world.

Related to that, it still makes me happy every time I think about Looking for Alibrandi winning the AFI over Chopper, because stories about teen girl feelings are never viewed as important as men maiming each other.

[Laughs] Oh my god! I love that you’re mentioning that! As much as I felt squeamish watching Chopper, I just thought Eric Bana was amazing. It was a great film, but just the idea of little Josie Alibrandi, 17-year-old Italian girl from the suburbs [beating Chopper] it just sticks at the back of my mind.

Also, the movie came out the same day as Gladiator. [Laughs] We didn’t think it had a chance! We were up against the big boys, and I’m still glad that Josie Alibrandi was the first Australian teen on film in the 20th century. It’s still something that I’m proud of.

Be honest: do you ever feel bad that you made the whole country cry when John Barton died?

I never imagined that’s where that story was going to go. I didn’t know until a couple of chapters before that it was going to happen that way. I sometimes wonder if I wrote that book today I actually don’t think I would have written about suicide because it has affected my life too much. It’s something I would have kept away from. I think after years and years I have come to terms with his death — which is weird for the writer to say that.

I realised how important he was as a character when it came to writing the film script. I was told to take the character out, because it’s closer to the end of the novel and they didn’t want people coming out of the movie theatre bawling their eyes out. So I had to find a way of keeping him in the film, because I didn’t want to pretend that stuff like that didn’t happen. But no, I never find pleasure in making people cry.

I was asked to be on the plotting committee for Dance Academy season two, and that’s the season where one of the main characters died —

Oh god, I know what you’re talking about.

I had nothing to do with that death, nothing at all! That was not a suggestion of mine!

Oh man.

I know. It’s so well done though. I had to watch it all in a row and I remember sobbing just for three episodes because the acting and writing was fantastic.

I think it’s so important that John Barton’s death was left in the film though, even if it does make me bawl every time. It’s such a turning point in Josie and her father’s relationship.

Oh, absolutely. It’s the catalyst for her to call him up and ask for help, and to realise the direction she wants to go in in life. But also — she is a bit of a whinger. I mean, the one thing about first person novels is that I had to remind readers that when it says ‘Oh, John Barton’s father was awful’ we’re seeing it through Josie’s eyes. And Josie had a very, I wouldn’t say black-and-white view, but she certainly saw things the way she wanted to see them. It was good to be able to burst that bubble and maybe start taking into consideration other people’s perspectives.

Were you ever apprehensive about writing the script for the film?

By the time they asked me to write it I had seen failed attempts of the script and I started thinking ‘I actually don’t want this made’. There were terrible stereotypes. I was asked to come on board and I thought, ‘Of course I can do this!’ and didn’t realise how difficult film scripts actually are to write.

The local references in the book and the film give Australian readers this nice sense of ownership of the story, even down to knowing which Maccas Josie would be working in. Did you ever feel pressure to dial back that Australianess?

No but I remember with the novel, people saying that usually they would cringe if they read something that made a reference to their area, and I just thought that was kind of interesting — but I still did it. I distinctly remember that I used to take the bus to work from Parramatta Road and it was when the McDonald’s on Parramatta Road was being built, so in my head that’s Josie’s McDonald’s.

My favourite scene in the film is Josie and Jacob on the motorbike going across the Anzac Bridge, the look on their faces. They’re obviously not riding those bikes [laughs] but it’s just such a great scene.

I only knew the Coke sign because of Looking for Alibrandi.

Maybe I should give a walking tour of Sydney, with Saving Francesa references as well.

Ah, people will make you do that now.

Okay!

Finally: do you ever think about what happened to Josie and Jacob? I think about it.

[Laughs] I was saying this the other day: most times I leave things opened-ended, it’s up to the reader to decide what happened with Josie and Jacob. So there’s that. There’s what you think happens to Josie and Jacob and what I think happens to Josie and Jacob, which is irrelevant.

Okay.

But of course Josie and Jacob end up together. In my head, of course they do!

—

Melina Marchetta appears at the National Writers’ Conference on June 17 – 18 as part of the Emerging Writers’ Festival. Earlybird tickets are available now.

You can also see Melina Marchetta and Pia Miranda at Sydney Writers Festival on May 28 for ’25 Years of Looking For Alibrandi: Have a Say Day’. Tickets are available now.