Kids In Detention Have Spoken Their Minds About Australia In The New “Forgotten Children” Report

“I don’t like to write anything to you. Because I don’t believe in you, in noan of you. You’re nothing but a cult of racist, liers who’s aim is to kill the peoples even childrens in Nauru.”

The collected findings and recommendations of the Human Rights Commission’s inquiry into children in detention, “The Forgotten Children Report,” was tabled late last night after most of us had packed it in and clocked off for the night. This was no impasse, however, for the journalists whose forensic and detailed coverage exposed the grisly details.

The Report’s findings are shocking, including that “prolonged detention of children leads to serious negative impacts on their mental and emotional health and development.” Within the last 24 months, 167 babies have been born in detention. The average length of detention for children and their families is one year and two months. There have been hundreds of incidents of actual or threatened self-harm.

The release of the Report is significant for a number of reasons; it exposes institutional and systemic abuse and it offers powerful suggestions to begin to right a multitude of wrongs. But chief among them, it provides first-hand accounts of those in the crosshairs of the Department of Immigration and Border Control: infants, whose entire world has been mapped out by barbed wire borders; teenagers, for whom words like “education” and “freedom” are Janus-faced concepts of hope and despair; and parents who fled countries ravaged by war and chaos, only to find themselves locked up in a fresh hell of administrative terror and ritual torment.

It’s not by accident but design that we usually find ourselves sheltered from the plight of those in detention. Journalists are often hamstrung by the private security firms charged with running detention centres and obfuscating efforts to peer inside their workings. Legal barriers compound this logjam. Policies adopted in 2012 require news outlets and their reporters to sign a “deed of agreement,” which can unilaterally be rejected for vague “operational and security priorities”. The requirements are deliberately onerous; they were modelled on the media access policy used at Guantanamo Bay.

The public submissions to the Inquiry make for harrowing reading. Testimonies from detainees point to ramshackle living conditions, fragile mental states and – overwhelmingly – a yearning to be free.

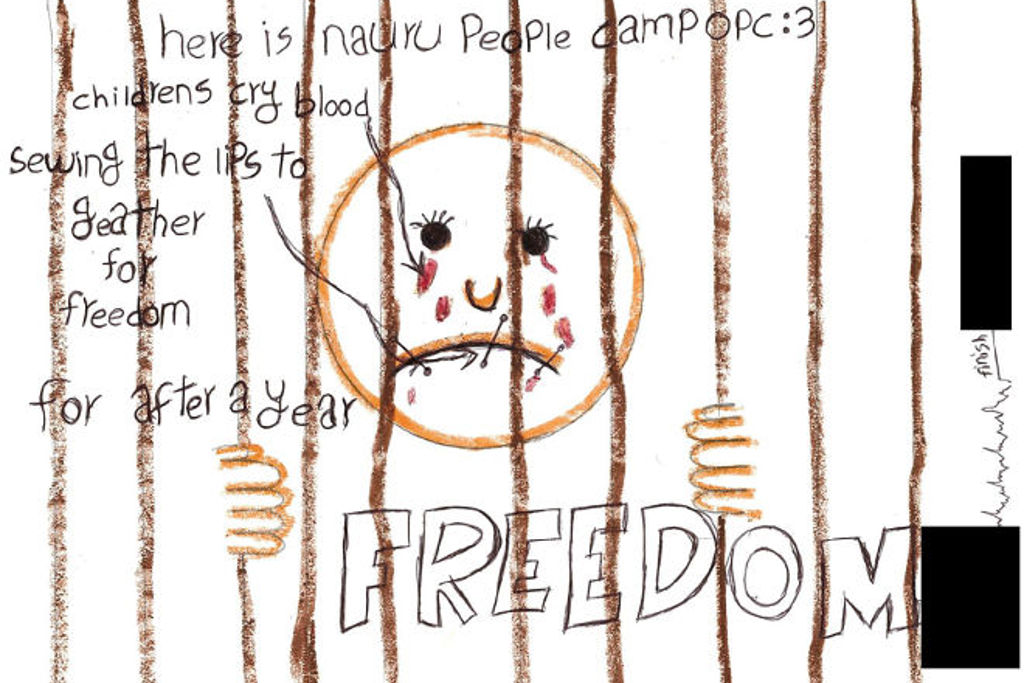

Submission No 63 – Name withheld – Child detained in Nauru OPC

“I want to tell you about my life in Nauru,” one submission begins. “But please do not get bored when you are reading.”

“Our tents are dirty and it’s become flooded when the rain begins,” the child describes. “After the tents have leaks and holes.”

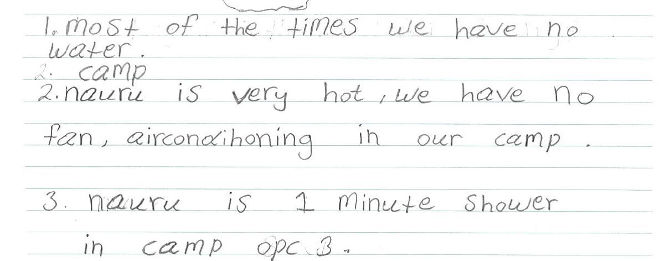

“The toilets are very dirty and it’s become filthy when we don’t have water in the camp and sometimes we don’t have water to wash our clothes and we do not have water to have showers.”

According to the detainees, water is a rare and precious resource. Several used their submissions to discuss its scarcity and, consequently, the minute-long showers they have to take. Last January, Guardian Australia reported water pumps at Manus Island had broken down, forcing a thousand men in detention to shower with bottled water.

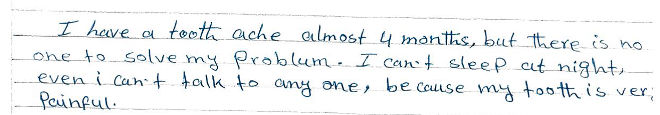

Medical care is also reportedly sporadic. In 2013, a group of doctors wrote a 92-page “letter of concern” that alleged “numerous unsafe practices and gross departures from generally accepted medical standards” were a regular occurrence at the Christmas Island detention facility.

“I have a tooth ache almost 4 months, but there is no one to solve my problem,” another submission reads.

“I put a lot of request for the Dentist but the only answer that I have got, there is just one dentist. You have to wait for 6 months.”

Submission No 20 – Name withheld – 17 year old asylum seeker

Weariness, fatigue and despair make an appearance, in either form or substance, over a number of submissions.

In 2014, a visiting psychiatrist reported that children in detention felt “jailed, demeaned, always watched”.

“I am a UAM” (bureaucrospeak for an “Unaccompanied Minor”), one detainee writes.

They describe the violence that occurred in Pakistan and prompted their attempt to escape: “There were many bomb blasts, and always big wars, and terrible attacks. Shia people have arms, legs, noses, hacked off, necks slashes, plus there is rocket fire and missiles.”

However, leaving the region did not provide them with the relief they sought.

“The worry of my life is not gone it is only getting worse. The tension, the worry about my own life, and the life of my mother and my brothers and my sisters is eating me up.”

Cataloguing their symptoms, they write: “I am very isolated. I have insomnia. I can’t sleep. I worry all the time about my future.”

Submission 227 – Name withheld – Parent detained with child on Christmas Island

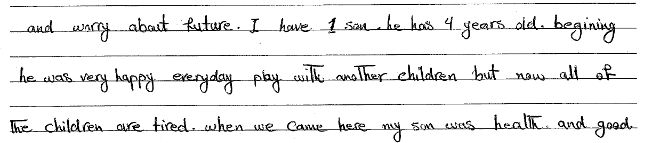

Another detainee, who spent more than a year on Christmas Island, relates the prolonged effects of detention on their child.

“I have 1 son, he has 4 years old. beginning he was very happy everyday play with another children but now all the children are tired.”

“The word of ‘Suicide’ is not an unknown for children anymore,” another father detained with children writes. “They are growing up with these bitter words. Last week a mother took to suicide in c.c compound. All children were scared and crying.”

“How can we remove these bad scenes from our kids’ memories?” he asks.

Submission No 194 – Name withheld – Child detained in Nauru OPC

“I want freedom.” It’s etched and written in a number of missives. It’s a recurring, desperate, basic plea.

“Freedom” has become a kind of watchword for the libertarian right. Tim Wilson, dubbed the ‘Freedom Commissioner,’ fought for the repeal of Section 18C on the basis of freedom of speech. But for those in detention, freedom has a far more visceral, more muscular definition.

“I don’t like to write anything to you,” begins one child detained in Nauru. “Because I don’t believe in you, in noan of you. You’re nothing but a cult of racist, liers who’s aim is to kill the peoples even childrens in Nauru.”

Another asks: “It has been more than 6 months that the immigrants are at the Nauru Camp. Why?”

The Forgotten Children Report does not provide an answer, but its findings do cast light on the shadowy government apparatus responsible. Acting upon the report’s many recommendations, including a Royal Commission, appointing an independent guardian for unaccompanied asylum seeker children, and government-provided mental health support for all children detained by various Asutralian governments since 1992, may be the meaningful response we can ultimately give.

You can read the full report here.

–

Justin Pen is a freelance writer. He tweets@justipen.