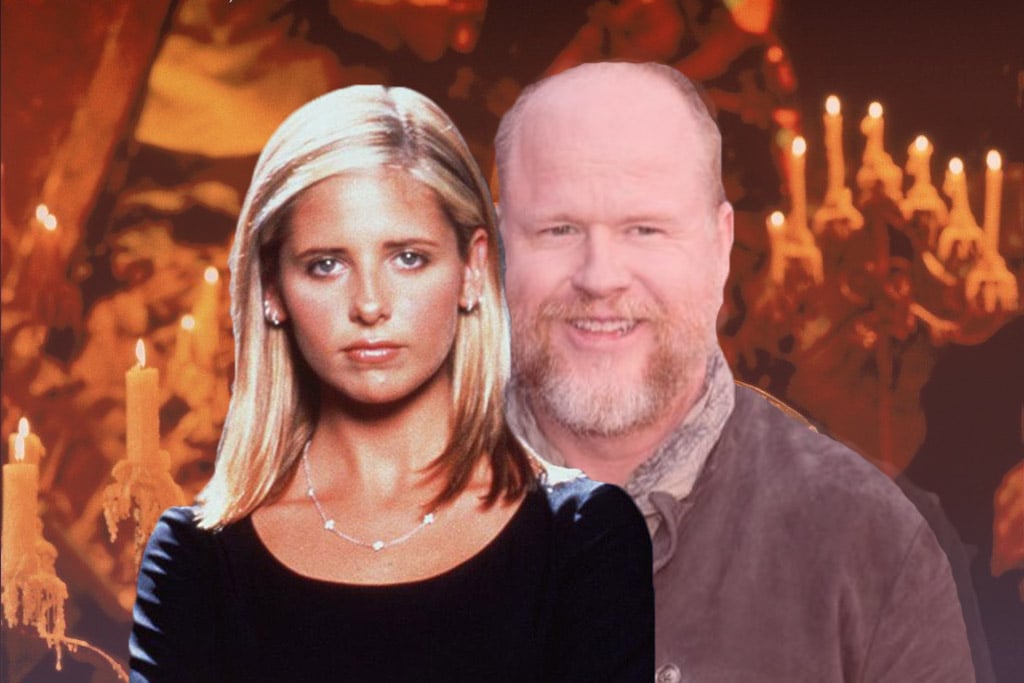

Was Joss Whedon The Real Big Bad Of ‘Buffy’?

Season 6 of 'Buffy the Vampire Slayer' proves that Joss Whedon's misogyny was only shallowly buried beneath the feminist surface.

More than once in my life — faced with something hard, lonely or unfathomable — I’ve asked myself, ‘What would Buffy do?’

Even in vulnerable moments, the teen vampire slayer could whip up a one-liner and a plan of action. In the season three episode ‘Helpless’, Buffy’s mentor strips her superpowers away to make her face a coming-of-age ordeal: to best a relentless vampire foe without her super strength, perception or agility. Buffy is reduced to just a girl.

Never fear: once her mum’s life is put in danger, Buffy’s supercharged survival skills (and wit) kick in: ‘If I was at full Slayer power,’ she says, ‘I’d be punning right about now.’

This is not the first time nor last time that Buffy’s daily world-saving will be nudged along by a li’l traumatic God in the Machine. But, in these early days, all this sits against a backdrop of normal life: school, parties, and absent dads. Buffy the Vampire Slayer perfected this dynamic: the Monster of the Week is always a metaphor for the everyday horrors of growing up.

Buffy coined the term ‘Big Bad’ — a kind of seasonal antagonist or level boss. For the first few years, the show’s Big Bad is a particularly nasty vamp or a very hangry mayor — but, really, it’s high school. By season six, the metaphors are stripped away: Buffy’s Mom has died of natural causes, her mentor Giles has left town, and Buffy has to flip burgers to pay the bills — just like the rest of us. Did I mention she’d also been dead and buried — then resurrected for the convenience of the friends she left behind? Well, that too.

It’s no surprise, then, that the Big Bad of season six is a very real-life problem: misogyny, represented by three young human nerds called the Trio. Imagine if incels had magic powers: that’s Warren, Andrew and Jonathan. They’re played for laughs — their foibles infantilised — until their ringleader, Warren, magic-Rohypnols his ex — to death.

The inhabitants of the Buffyverse are no strangers to misogyny. A ground-breaking girl-power show of its time, Buffy consistently and subtly reinforces the status quo through Nice Guys™, like Buffy’s forever-friendzoned sidekick Xander. Toxic masculinity justifies the actions of Buffy’s friends and boyfriends long before The Trio felt entitled to anyone.

But this season six tone shift — from teen horror-dramedy to miserable realism — does something new: Buffy’s core characters, so lovingly built, are increasingly mined for trauma. It’s heavy viewing, and reveals that Whedon’s 1990s ‘girl power’ credo was as much a bait-and-switch for viewers as it was (allegedly) for those working under him.

Buffy’s resilience, wit and compassion shaped my childhood (and wardrobe, and pet’s names, and tattoos…). This is why I find season six so difficult to watch: the Trio are just synecdoche for a punishing misogyny that saturates the season — which shows contempt both for the characters, but also for the viewers who love them. Buffy’s strong women are built up only to be slowly, surely broken down.

How? Season five gifted us a developed same-sex relationship between witches Willow and Tara; then, season six taketh away, with Willow subjecting Tara to coercive control before Tara is shot dead by Warren. BtVS buries its gays just to further Willow’s character arc, from the Slayer’s mousy bestie to vengeful world-destroying witch.

Xander, visited by the Ghost of Marriage Future, is so frightened of his own toxic masculinity that he leaves his bride-to-be, Anya, at the altar. She, too, becomes a vengeful demon in her grief.

Buffy’s deep depression permeates the season. There’s a kind of pro-life logic here: her trusty Scooby Gang wanted Buffy alive to take care of them (and the world), but once the dirt is rinsed from under her fingernails, they don’t notice she’s not fitting in among the living. The Chosen One’s destiny is now bills and busted pipes and an orphaned little sister, Dawn, who’s not coping either. Then there’s Spike, a vampire whose ‘crush’ on Buffy (read: stalking) is often played for laughs or will-they-won’t-they tension. When they finally go there, their relationship is dysfunctional, aggressive and desperate; when Buffy leaves him, he overpowers her and tries to rape her.

The late Kat Muscat wrote the definitive piece on Spike — both on rape as a trope used to ‘humanise’ or ‘complicate’ female characters, and also on Spike’s veracity as an attempted rapist. The plot around this event is realistic: Spike doesn’t leap from the bushes, but is known to Buffy — nor does he disappear into the bushes. He sticks around to make, as Muscat put it, ‘sad-puppy apologies’.

The metaphors are out the window: Monsters of the Week are all sideshows to the hopelessness of relationships, grief, expenses, jobs, and staying alive. The plot of season six repeatedly makes its female characters suffer in order to set up their next trauma and/or mistake: Willow kills Warren; Anya slaughters a dozen frat boys. Buffy’s mentor and her ex-boyfriends get to leave town, but Buffy has to stay to clean up everyone’s messes — while working at a fast-food joint called Doublemeat Palace.

Buffy represented the relatable loneliness of growing up feeling misunderstood. Her fantastical high-school struggle showed us what we could survive. Sunnydale was a safe space: the magic kept the scary stuff of real life at arm’s length.

Then, in season six, Buffy is stripped of her dignity and hope, with little relief for either her or the viewer. Fan-favourite musical episode, ‘Once More with Feeling’, even plays up this trope: a Zoot-suited demon forces characters to sing Broadway revelations of their secret pains — until they self-combust.

In his 2006 Equality Now awards-night speech, series creator Joss Whedon famously said, ‘Why do [I] always write these strong women characters? Because you’re still asking me that question.’ In that same speech he called misogyny ‘life out of balance…sucking something out of the soul of every man and woman who is confronted with it.’

Season six digs up Buffy’s corpse, jumps the shark, and throws off the balance — unmasking the likes of Xander, Spike, and the Trio to show us who is underneath.

In 2017, Kai Cole — Whedon’s now ex-wife of 16 years — alleged that Buffy’s creator and showrunner used feminism as a shield to conceal multiple affairs conducted on and off set, and that Cole ‘carried the burden of Whedon’s long-term deceit and confessions’ until she was diagnosed with C-PTSD. And now, four years later, Buffy the Vampire Slayer is having its own #MeToo moment, with Charisma Carpenter (who played Cordelia on both Buffy and its spin-off Angel) alleging Whedon ‘disempowered’ and ‘alienated’ her. Like Cole, Carpenter says the burden of these memories ‘weighed on my soul like bricks for nearly half my life.’

In an Instagram post, Sarah Michelle Gellar (Buffy) wrote, ‘While I am proud to have my name associated with Buffy Summers, I don’t want to be forever associated with the name Joss Whedon.’ Michelle Trachtenberg (Dawn, Buffy’s teenage sister) has alleged that Whedon wasn’t allowed to be alone with her after ‘inappropriate’ incidents took place on set. Amber Benson (Tara) tweeted that Buffy’s toxic work environment ‘started at the top’. Marti Noxon, writer of many of Buffy’s most beloved episodes, recently described how Hollywood’s romantic notions of the ‘difficult genius’ repeatedly ‘enable abusive people and systems in the name of art’.

Buffy’s sixth season (2001) coincides with the third season of its spinoff, Angel. It was during Angel’s fourth year (2002) that Carpenter alleges much of Whedon’s misogynist bullying took place. Through its seven-season arc, Buffy’s ‘strong women’ characters are manipulated to shield and normalise toxic masculinity. Buffy’s suffering — and Willow’s, Tara’s, Cordelia’s and Dawn’s — plays out while another ‘difficult genius’ allegedly subjects his employees to treatment that many of them, as Benson puts it, ‘are still processing 20+ years later’.

Whedon hid behind his Buffy. It was a good disguise for a little while.

In second-season episode, ‘Lie to Me’, Buffy is crushed by another deceitful suitor-turned-bad-guy. No one seems to be who they say they are. It seems fitting that Whedon wrote this episode himself. Buffy asks father-figure Giles to spin her a fairy-tale version of their world.

“It’s terribly simple,’ he says: ‘the good guys are always stalwart and true, the bad guys are easily distinguished by their pointy horns or black hats and, uh, we always defeat them and save the day.”

“Liar,” says Buffy.

Zenobia Frost is an award-winning writer, poet and Buffy stan based in Brisbane. She will still go on about the ‘good old days’ of Sophie Monk’s season of The Bachelorette in 2051. @zenfrost / www.zenobiafrost.com