Why Teenage Girls Crush Hard On The Bad Boys

Nice girls aren't supposed to love murderers. Is that why they always do?

In Grade Nine, a girl in my English class called Sumita stood in front of the blackboard and recited a love poem she had written to Daniel Radcliffe. That week, we had been assigned to write about somebody important to us. Most of us wrote about our mothers and grandfathers and aunts. Sumita wrote about Daniel Radcliffe. Sumita’s love for the then 14-year-old Harry Potter actor was a well-known fact of everyday life in my girls’ school in suburban Sydney. While I had been dismissive of her inclination to decorate her laptop, school diary and pencil case with the bespectacled face of an adolescent wizard, it was only as she read her poem in front of our class — and got increasingly teary with emotion — that I realised the intensity of her feelings for Daniel Radcliffe were much the same as my devotion to Kurt Cobain.

When you’re a teenage girl, you crush hard. All of a sudden you go from wandering around the backyard reeking of chlorine and sunscreen with ice cream smeared over your cheeks, to somebody who converts their bedroom walls into a miniature shrine to some famous, far-flung, beautiful boy or girl you will more than likely never meet.

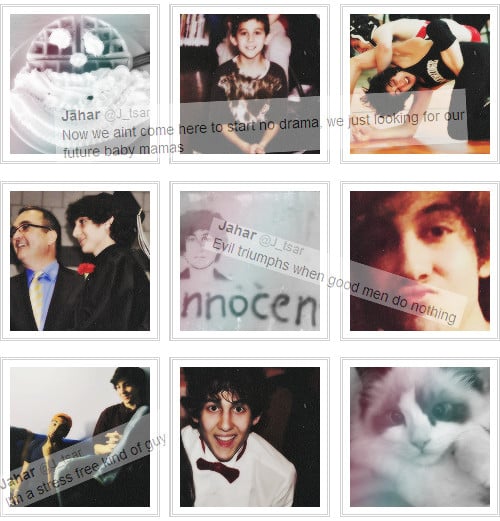

The topic has been flung into the headlines in the last few weeks, due to one dark-haired, bedroom-eyed boy and the community of teenage girls who have been overcome with adoration for him. That person is Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, one of the young men accused of the Boston Marathon bombing.

I Heart Jahar

Last week, Rolling Stone published an in-depth piece about Tsarnaev and, in a controversial decision, featured his picture on the cover of the magazine. The piece describes the 20-year-old Tsarnaev (‘Jahar’ to his friends) as “a beautiful, tousle-haired boy with a gentle demeanour, soulful brown eyes and the kind of shy, laid-back manner that ‘made him that dude you could always just vibe with.” To those who really knew him, at least.

But also to the hundreds of teenage girls who have gathered under the slogan of Free Jahar. Those girls are one of the reasons why the Rolling Stone cover has been perceived as so troubling.

Being on the cover of Rolling Stone is symbolic of rock stars who have finally ‘made it’, of people who define the cultural zeitgeist. For those insisting on the unparalleled evil of somebody who would, with his older brother, detonate a bomb during a marathon, the Rolling Stone cover comes dangerously close to legitimising the voices of the Free Jahar fangirls, and threatens to destabilise the narrative of the ‘remorseless killer’ that the American political establishment is fighting so hard to preserve.

The wave of female affection for ‘Jahar’ has been well-documented. Last week, Amanda Marcotte, writing for Slate, framed the Free Jahar fangirls as prison wives in the making, crushing on a killer because “the fantasy of getting attention from a famous murderer is easier to realize than the fantasy of attention from other celebrities.” Another article by Hanna Rosin, also for Slate, analysed the adoration as a form of misplaced maternal instinct — a bunch of women yearning to make Tsarnaev a sandwich and then snuggle him to sleep, with some restorative sex thrown in for good measure. And while the commentary keeps itself in check by maintaining a tone of sociological distaste for anyone who would rally behind a killer, all the pieces seem to be whispering, “Yes, this boy is an accused murderer who has shown no public remorse for an act of atrocious violence. But dude’s a babe.”

Last year The Awl published a brilliant essay written by Rachel Monroe, which pointed out that it’s not unheard of for mass murderers like James Holmes of the Aurora, Colorado shootings, and the Columbine High School killers, to inspire communities of adoring teenage girls. These girls converge on Tumblr, the online equivalent of the bedroom wall, obsessively posting photos, quotes and videos, feverishly expressing love for these boys who society at large reviles. Monroe points out that while some read the public performance of sexual obsession with killers as worrying, particularly because the girls in question are so young, in a way there’s really nothing new going on. “Teen girl sexuality — like, well, adult human sexuality — can edge up against the dark and the illogical, even when the crush object isn’t a murderer.”

I Heart Kurt

Teenage girls aren’t supposed to love murderers. We can deal with girls swooning over Justin Bieber or Daniel Radcliffe because both those men are boys with hairless chests and, until they piss in a bucket, wholesome personas. They make sense in the cultural narrative we have about sex and teenage girls.

Society is constantly up in arms about ‘sexualisation’. We worry that little girls are being marketed a ‘pink princess’ fantasy, that they’re wearing padded bras and hair extensions, and that by the time they reach thirteen their heads are so full of Rihanna and Nicki Minaj and hardcore porn that it’s no wonder they’re sexting left, right and centre. The narrative says that any young girl who expresses sexuality must have been produced by sexualisation and is therefore deviant, but passively so. Any sexuality she expresses is automatically deemed inauthentic because ‘normal’ girls are asexual and ‘normal’ girls like Justin Beiber.

So when all the world seems to be saying that teenage girls want nothing more than that, crushing on dangerous, destructive, even violent boys, feels like an act of resistance.

The men I swooned over when I was thirteen were dark and brooding and brilliant. They were men who suggested some sphere of the possible just beyond a suicide pact. They were men who made my mother worry. Foremost among them was Kurt Cobain, doubly inaccessible because not only was he famous but he had also been dead for a decade. I would lie in bed every night listening to Nirvana’s MTV Unplugged In New York album through my headphones and swoon at the very fact that I could hear him exhale into the microphone. Just the fact that I could hear him breathe set off a chaos of feeling which was completely beyond any language I had to express it. A girl with a crush often feels like that. She inhabits a force field of emotion that is beyond words, beyond rationality, beyond being told to calm down.

I Heart Paul (Not John, George or Ringo)

A girl with a crush is very often told to calm down. Her intensity freaks people out. It’s destructive and expressed in so many exclamation marks and emojis as to fall into the incomprehensible.

50 years ago, society saw the birth of the ultimate fangirl: the thirteen-year-old being restrained by a policeman as she shrieks for The Beatles. Beatlemania was a particularly disturbing movement for parents. The same girl who played cello and went to bed at nine o’clock with a glass of warm milk would squirm under a barricade and scratch at the face of a policeman with her fingernails when a Beatle was occupying the same street or airport or theatre. To adults, Beatlemania was an epidemic. It was a disease that made young girls sob uncontrollably or scream until they fainted or came down with laryngitis. It was an affliction sweeping the nation, with young girls (mostly white and middle-class) the most at risk.

Barbara Ehrenreich, Elizabeth Hess and Gloria Jacobs, writing about Beatlemania as a sexually defiant subculture, explain that “to abandon control — to scream, faint, dash about in mobs — was, in form if not conscious intent, to protest the sexual repressiveness, the rigid double standard of female teen culture… It was the first and most dramatic uprising of women’s sexual revolution.” Having Beatlemania was subversive. It was to sublimate romantic and sexual yearning, for which you didn’t yet have words in the utter wildness of your body and behaviour.

A teenage girl with a crush is unruly, a figure of disorder, because she’s yet to understand what’s happening to her. Those feelings occur in a raw, voiceless place, beyond the stuff of everyday life. And we have historical precedents that show what happens when that intensity of emotion doesn’t have an outlet.

I Heart Jesus

In the 1730s, a kind of proto-Beatlemania swept Paris in the form of the convulsionists of Saint-Médard. In 1727, a priest named Francois de Paris died of self-starvation and was buried in the cemetery of the Saint-Médard church. His tomb became the site of reported miracle healings and manifestations of Christ. Pilgrims, overwhelmingly pious young women, began to travel to the church, eating the dirt covering his grave, upon which they would erupt into ecstatic religious trances and convulsions that were strikingly erotic, touching themselves and mimicking the act of sex. All because of Jesus.

Soon there were hundreds of girls, and they found new extremes of self-mortification to go to. They had themselves squashed beneath paving stones, they pierced their tongues, they swallowed hot coals, they had themselves hung up by their ankles and beaten with sticks. The girls were so disruptive that in 1732 the cemetery was sealed and King Louis XV, exercising his control over the heavens, declared God was forbidden from working any more miracles at the grave.

But that didn’t stop the girls. In fact, the mania was such that soon after the cemetery was sealed, nuns at a nearby convent erupted in a chorus of spontaneous meowing at the same time, every day, for several hours. The royal guard had to be called in to silence them.

A hundred years later, doctors in Paris retroactively diagnosed these girls with hysteria. Hysteria is a disease that no longer exists, but one which was once widespread and largely affected young women. Today, if somebody presented at a hospital with hysterical symptoms, they would probably be diagnosed with schizophrenia or conversion disorder or bipolar disorder. But that doesn’t mean that hysteria was not ‘real.’

Hysteria is one of those diseases located at the tricky intersection of psychosomatic and somatic disorders. It has both biological symptoms, while also being socially determined. There are still illnesses like hysteria which stubbornly resist biological explanation, diseases that overwhelmingly affect young women, like anorexia, chronic fatigue syndrome and multiple personality disorder. Moreover, those diseases — like hysteria — are thought to be contagious and spread by suggestion or imitation. They are diseases acquired, in part, through being female and young in a culture where women’s freedoms and choices are complicated, a response to society expressed through the body.

Fangirls, hysteria, and defying the pressure to be a good girl

Asti Hustvedt, in her book Medical Muses, documenting the experiences of three patients of the infamous Salpetriere hospital for hysterics, describes the conduct of a girl named Genevieve, whose behaviour looks very similar to the religious convulsionists and Beatlemaniacs. Genevieve had visions and trances. Hopelessly in love with one of the doctors at the hospital, she would frequently erupt into what the medical notes called “erotic delirium”, falling on the bed, lifting her skirt, spreading her thighs and asking doctors to kiss her. But Genevieve was extremely pious, a ‘good girl.’ It was only in fits of hysteria that she became wild. She broke windows, stole wine and chloroform, fought with the other patients and hid on the roof. That was the thing about hysteria. The body exploded with feeling, expressing a narrative for which words were insufficient, or which could not consciously be processed.

No one would argue that Western society is as repressive as it was in the time when hysteria was in its heyday. But a teenage girl with a crush bears a striking resemblance to the screaming, wild women of history, fangirls for Jesus, for the Beatles, for whatever gave them a reprieve from being a ‘good girl’ for a while.

The girls crushing on Dzhokhar Tsarnaev and other killers are the end-point of contemporary fangirl hysteria. It’s a point of defiance when society gives you so many conflicting messages about who you’re supposed to be. When you’re a teenager, when you have only the haziest idea of what sex is and what it means to you, a crush is a way to vent strong emotions and desires. You are irrational because you don’t fully understand where these feelings come from or what they mean, and you don’t yet have a handle on the language to be able to articulate what’s happening to you. But you learn. Before that happens, when the world is telling you to be a good girl, crushing on bad boys is, in a dizzy, unformulated way, a form of defiance.

–

Madeleine Watts is a Sydney-based writer. She is a regular contributor to Concrete Playground and Broadsheet Sydney.