Alex Gibney On ‘Going Clear’, And The Psychological Intimidation Of The Church Of Scientology

After our writer completed this fascinating interview, she received an email from Scientology HQ...

Name a political scandal of the last ten years and Alex Gibney has probably made a film about it. From Enron (The Smartest Guys In The Room) to the American military and torture (Taxi To The Dark Side); from Lance Armstrong (The Armstrong Lie), to Julian Assange and Wikileaks (We Steal Secrets), to paedophilia in the Catholic Church (Mea Maxima Culpa). Alex Gibney makes documentaries about horrible, powerful people, horrible, powerful institutions and the individuals who rebel against them.

The American filmmaker’s latest documentary continues along this strain: Going Clear explores one of the most ominous and mysterious phenomena of the last 50 years: Scientology.

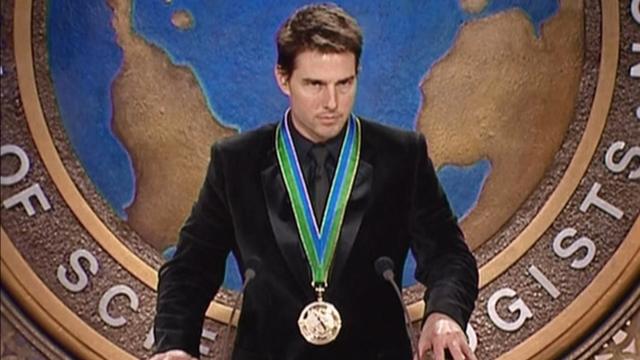

Based on Lawrence Wright’s groundbreaking book of the same name, the film covers the history of Scientology and its creator L. Ron Hubbard; the doctrine of the religion; and, most controversially, allegations of physical and emotional abuse by the Church of Scientology since the 1950s. Going Clear also discusses the reasons why Scientology poster boys John Travolta and Tom Cruise have stuck with the institution for so long.

People who are already fascinated by Scientology will probably know everything there is to know about ‘auditing’ (the process of ‘self-knowledge’, which is a cross between hypnosis and psychotherapy, allegedly used to blackmail members into staying), ‘Dianetics’ (Hubbard’s ‘spiritual healing technology’) and ‘disconnection’ (severing ties with ‘suppressive persons’ who criticise the Church), interviews with former high-ranking members reveal some previously unheard claims against the Church.

For this reason, the Church of Scientology have fought vehemently against Going Clear’s release for over a year, picketing HBO, making damning films about Gibney and other participants, and taking out full page ads in The New York Times criticising the documentary’s inaccuracies. Going Clear still cannot be shown in the U.K.; HBO was said to have given 160 lawyers the task of overseeing the film.

Alex Gibney has done things like hang out with Julian Assange and win an Oscar, so I was pretty excited to interview him — and even more chuffed when he tweeted about me immediately after our chat. What a nice guy!

Except it meant that less than a week after I interviewed Gibney, before I had even written the piece, I got an email from the Media Relations department of The Church of Scientology.

The email referenced Alex Gibney’s tweet, directed me towards this video, and urged me to “avoid the same errors Gibney made”. It was signed off by the American spokesperson for The Church of Scientology Karin Pouw, a name I recognised from articles about film critics being harassed after reviewing Going Clear.

You don’t realise how mysteriously threatening you actually find the Church of Scientology until you receive an email from their head office at 8.37am on a Wednesday morning, and instantly feel the kind of raw panic usually reserved for sending a snarky text to the wrong person. Why was I so anxious about this email, which really wasn’t that menacing? But of course, this is one of the Church’s greatest achievements: making themselves appear so incredibly intimidating and all-knowing, that an otherwise innocuous email seems like a horrible threat. They don’t need to do any more than that to scare you into submission; the fact that they know who you are is scary enough.

It made me realise how much Alex Gibney must have wanted to make this film — enough that he didn’t care about incurring the wrath of the creepiest club on the planet.

–

Junkee: Congratulations on Going Clear. Everyone I know is obsessed with it.

Alex Gibney: Well, that’s good.

Given the claims made against Scientology, and rumours about particular individuals involvement with it, I’m guessing you had information that perhaps you couldn’t put in the doco for legal reasons. How different would the film have been if you were free of those repercussions?

(Laughs) Free of repercussions, now that’s an interesting question! How different would all films be if they were free of repercussions?

I don’t know, I think that there are certainly some stories that I may not have been able to tell, but at the same time I think what we did get to tell was pretty representative. So I don’t think it was fear of repercussions so much as it was trying to tell a story about the individuals that I focused on, rather than running the gamut of the tale of Scientology.

Was HBO very concerned going in?

They were concerned, but I must say, they were, I think, heroic. They backed me up rather admirably, they asked a lot of tough questions. They wanted to make sure we had done our homework — not just in terms of what we put on the screen, but also that we had the backing to be able to withstand any kind of legal attack that might ensue. But they were very brave and very supportive, so in that sense they were just the ideal partner.

The doco does a great job of explaining how people like Paul Haggis can stay in Scientology for 35 years, but why do you think it so easily hooks people? Why Scientology, and not something else?

You ask a fundamentally good question, in the sense that this idea of ‘the prison of belief’ is not limited to Scientology. The notion that people will get lost in a belief system, whether it be political or religious, is certainly not confined to Scientology. It is, as you suggest, something that is deeply human; we have a need to find a simple belief system that means that we don’t have to think for ourselves anymore, as Paul Haggis suggests at the end of the film. Because it’s comforting – it’s exhausting to think for yourself all the time!

But bad things can happen when you let others do the thinking for you. That’s part of what happens in Scientology. In getting into Scientology — unlike being told about the virgin birth the first time you walk in the door, if you’re considering being a Catholic — you go through a kind of therapy that’s very pragmatic, and it makes you feel good. And you want to keep feeling good, so you keep going back, and then you’re maybe urged to pay a few more upper level auditing sessions, and the next thing you know you’re on the path.

The path initially for Scientologists is a very pragmatic one: ‘How can I make myself feel better? How can I remove some of the anxiety from my life that is holding me back from doing great things?’

You’re very respectful of your subjects. Even when some of them are discussing doing awful things, you don’t get the impression that they’re being laughed at or judged. For the former members who you don’t often see in the media, how did you gain their trust?

Part of gaining trust is convincing people that you’re going to honour their testimony, and that you’ve got some sort of fundamental empathy with their situation. That you will listen to them and that they will be fairly represented; trying to convince them, either through past work or conversations, that you really will hold sacred their testimony, and won’t take advantage of it.

You can see some of the interviewees are processing it all in real time. It would probably take years to unravel all that conditioning.

You’ve raised something very important I think, which is one of the things that most surprised and interested me in doing this film: how hard it was for many of these individuals to let go of Scientology. To leave the prison cell even though the door was wide open. It took years in years in many cases — and you’re right, you can see them on screen processing that.

When I asked Marty [Mark] Rathbun, the former number two guy [a former senior executive of the Church], I said, “Was there anything that you regret?” — and you can see that it’s torturing him, it’s like he’s in a sweat lodge and suddenly perspiration is pouring off of him. It was in that mode that he also let on that he was responsible for the wire tap of Nicole Kidman. He hasn’t revealed that before, and I think that he revealed it this time because he had come to a place where he didn’t want to be held back by any more secrets; he felt that the way forward was to expunge those secrets, [so] his past wouldn’t have the hold on him that it did.

But it takes years for people to get to that point, and I think that Marty would say that it took him years, because when he first got out he basically thought of himself as a Scientologist who just didn’t like the current administration. In time, he viewed the world much differently.

Some of the interviews are so distressing that I wondered if it had a similar feeling to being audited. Did that cross your mind while you were conducting these interviews, and having really sensitive conversations?

Very much so. Indeed, the main title sequence is constructed to convey that idea: you hear a woman asking auditing questions and at some point it changes from her to me, the music disappears, and you hear me ask a very simple question of Paul Haggis. And that’s where the film starts. I do think that interviewing is a lot like auditing; I thought about it at the time, and I thought about it a lot in the cutting room.

You’ve made very popular films about Enron and the Catholic Church, the American military, Wikileaks and Lance Armstrong. A lot of your films are about abuses of power, and organisations or individuals misusing their influence. Of all the powerful institutions you’ve exposed, which made you most nervous to criticise?

(Laughs) That’s a good question! Um… maybe the American military? I wasn’t criticising them as much as I was criticising the American government, because I think it was the Bush/Cheney administration at the time that hijacked the American military in a way that many soldiers deeply resented.

Scientology beats its chest a lot, but I don’t think that people should be so afraid of Scientology any more. I think that one of the reasons why people were afraid was that they managed to keep things so secret for so long, but I think it’s time for people to stop being scared of Scientology. It’s one of the things that Larry [Lawrence Wright, author of Going Clear] and I really agree on.

How soon after you started working on Going Clear was the Church of Scientology aware of it? Did they try to dissuade you during production?

Most of my production was focused on the dissident members until fairly late in the process. There were people we reached out to as part of our production, but we tried to keep a pretty low profile for a long time. I’m sure they were aware that we were around, but we didn’t go out and wave any big banners until pretty late in the game.

That’s when they started taking out full-page ads in the New York Times, right? Did you ever feel genuinely worried about the backlash? It’s pretty ugly on Twitter…

It is pretty ugly on Twitter! (laughs) They produced a documentary about me — they even went after my father to some extent, who has passed away so he can’t defend himself. Sometimes you have a psychological toll [to pay], but I’ve had experience with this already in terms of the kind of online barbs that were thrown at me when I made my film on Wikileaks and Julian Assange. The Assanganistas can be very hostile and aggressive online, in a way that surprised me. I don’t think it would take me aback now, but it did then.

It gets under your skin in a way that’s hard to describe, but it’s like, it’s just a tweet, why should it be bothersome? But it is bothersome. It does destabilise you psychologically, and I think that’s what Scientology depends on, but if you’re prepared for that it’s a lot easier to resist.

Did you experience the same kind of intimidation techniques the Church uses against Suppressive Persons or Potential Trouble Persons? I know they harassed some of your interview subjects.

I think they tried to intimidate me, but I know they went after subjects far more aggressively than they went after me. Maybe I’m not as good at this as I should be, but I don’t see private eyes following me down the street all the time. But I know that they’re doing that to a lot of people who are in the film.

There were a few times where people would turn up at the office, and they picketed HBO, I believe. But I didn’t get the kind of physical threats, or threats of loss of my house or income, or the kind of stalking that some of the other people received. There’s a lot of that that has gone out. Private eyes would turn up at people’s homes just to let them know they knew where they lived, as a way of saying, ‘We can get you if we want to’.

Oh god.

It’s very clever! It’s psychological intimidation.

Was there anything you uncovered that really shocked you, even after all your research? For instance, I have never been more fascinated about anything than I am about the Celebrity Centers [churches specifically intended to recruit famous Scientologists]; it seems crazy.

The Celebrity Center is crazy, they did go after some journalists very hard. We mentioned a bit of that poisoning pets, and thing like that. There’s a woman called Paulette Cooper who was on the receiving end of some really ugly stuff [the author/activist was targeted by ‘Operation Freakout’, an alleged plot by Scientologists to have her incarcerated in jail or a mental institution].

I think there was a lot more to the story of how the Church turned Nicole Kidman’s kids against her. There are ways of going deeper into this story; if you read Larry’s book, there’s a lot of evidence of stuff that I couldn’t put in. It goes pretty deep.

In the long run, what is your biggest aim with Going Clear? Is it challenging Scientology’s legitimacy to be tax exempt, or encouraging more people to leave and speak out?

I think there’s a bigger aim too, which is getting us all to think about the idea of the prison of belief. It’s very easy to look at those wacky Scientologists and say ‘I’m not one of them’, but I think all of us are prisoners of some kind of belief or another. If we’re not examining our motives toughly enough, then we’re possibly prone to doing appalling things as well, and excusing the kind of cruelty that Scientologists regularly excuse.

–

Alex Gibney has three films screening at Sydney Film Festival: Going Clear: Scientology And The Prison Of Belief (Saturday June 6; Wednesday June 10); Mr Dynamite: The Rise Of James Brown (Sunday June 7; Thursday June 11); and Steve Jobs: The Man In The Machine. He will be in conversation at Sydney Town Hall on Sunday June 7.

Going Clear: Scientology And The Prison Of Belief will be released nationally on Thursday June 18.

–

Sinead Stubbins is a writer from Melbourne who has done stuff for Yen, frankie, Smith Journal and Elle. She tweets from @sineadstubbins.