People Are Calling Out WA Police After A Young Woman Was Fined $500 For Stealing Tampons

On-the-spot fines are becoming more and more common, but we don't all pay the same price.

With a population of just 1,000 people about five hours in-land from Perth, the small town of Coolgardie isn’t often the focus of any national debate. And judging by their police department’s social media presence — which regularly features pictures of cops playing table tennis and air hockey at the local youth club — it’s not exactly a hotbed of crime either.

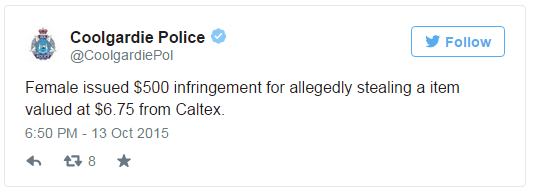

But this week, one seemingly innocuous tweet from the Coolgardie Police Department has started a pretty important discussion.

As people soon found out, the female in this case was a 20-year-old Indigenous woman and the item was a box of tampons. Advocacy organisation Essential 4 Women South Australia were among the first to publicly criticise the move, and press police for more information.

Though the woman undoubtedly committed a crime, to many, the severity of the police response seemed disproportionate.

@CoolgardiePol are you KIDDING? Do you know what it must be like to be so desperate to STEAL a tampon?? Where was the discretion?

— Essentials4WomenSA (@E4WSA) October 15, 2015

While the original tweet and the resulting correspondence have since been deleted, the police went on to defend the infringement, saying the woman had bought both food and soft drink. The implication was that the theft was more deliberate than it seemed; less a move of desperation than a willful disregard for the law.

This did not go over so well:

@CoolgardiePol that's the problem though. Women on low/no incomes are finding themselves having to CHOOSE between food or sanitary items.

— Essentials4WomenSA (@E4WSA) October 15, 2015

@CoolgardiePol @E4WSA What, so she can eat or menstruate?

— Celeste Liddle (@Utopiana) October 15, 2015

Moved to action by the perceived injustice, the group’s co-founder Amy Rust then launched a crowdfunding campaign with the intention of covering the woman’s $500 fine.

“Imagine the sheer embarrassment of getting caught doing such a thing, let alone having the police called AND THEN have them fine you for it!!” the page read. “The boys in blue couldn’t have said ‘put the tampons back, I’ll let you off with a warning, go use some newspaper/here’s a tissue to sort yourself out’? No? I’m thankful everyday I’ve never found myself to be in such a position whereby I can’t afford basic hygiene products like tampons but I damn well show a bit of empathy and understanding for those who can’t.”

In less than 24 hours, 86 backers had well-surpassed the original goal, contributing more than $1,500; as of this morning, they have raised over $3600, from 217 supporters. Rust is now on a mission to get the cash in the right hands.

In response to the mounting media coverage that resulted from the petition, the Coolgardie Police have given comment to The Guardian stating the woman was caught taking the product on CCTV, and was recognised by police. “Her excuse was she was stealing it for someone else who was too ashamed to buy it, which is probably true,” said Constable Brian Evans.

But that response has just lead to further questions: is that crime really worthy of its punishment? And what processes are followed in even making that call?

–

What’s The Deal With These On-The-Spot Fines?

Western Australian Police have only recently been given the power to hand out criminal infringement notices. Intended for those who commit low-level offenses such as disorderly behaviour, public urination, or theft worth under $500, the fines have been issued in Perth since March and were rolled out across the rest of the state from June.

The intention behind it is to simplify policing. Though they can later choose to contest the charge in court, when someone accepts an on-the-spot fine it works in the same way as a parking ticket. With no need to bring them back to the station, question them, or schedule court proceedings, the whole process means both police and the courts have more time to pursue bigger cases in a more timely fashion. It also means the perpetrators don’t have a criminal conviction recorded against their name.

This is a system Constable Evans from the Coolgardie Police praised when speaking about the young woman’s case. “Normally, prior to March, we would have to arrest her under suspicion, bring her back, do a recorded interview — it would have taken pretty much all day,” he said.

But as others have noted, there’s an important stipulation in all this about “discretion”. If officers see a petty crime in action, they’re not obliged to issue an infringement notice; the law states they can instead choose to “caution, summons, arrest on a case-by-case basis”.

@E4WSA @CoolgardiePol wondering why the officer who issued this fine did so when they had discretion to caution? pic.twitter.com/06sDxNuqlw

— Almaz (@Almaz001) October 15, 2015

If the Coolgardie Police had felt empathy for the woman, whose crime was possibly motivated by poverty, they could have let her off. If they’d felt empathy for her lack of legal access to an essential health item — a noted problem in Australia at large — they could have let her off. If they felt empathy for her excuse, allegedly helping a friend who was “too ashamed” to buy an item half the country’s population regularly use, they could have let her off. But for whatever reason, they didn’t.

With the process now made so simple, is it more appealing to just dismiss these matters with a fine?

–

This Is All Part Of A Larger Problem

NSW has had a similar on-the-spot fine system in place since 2007, and it’s been proven to be a little fraught. Though it achieved the desired effects of freeing up court time and simplifying policing, it was revealed that only one third of fines were being paid, and there was no evidence that the number of offences were dropping at all.

Moreover, a 2009 report by the NSW ombudsman showed the nasty results it had on people who couldn’t keep up with the costs — the kind of people driven to shoplifting due to a lack of cash in the first place.

“Delays in paying a $150 CIN penalty for swearing or $300 penalty for shoplifting will usually result in enforcement action, adding an extra $50 in costs to each penalty notice, plus another $40 for each time that enforcement action involves an RTA sanction,” the report read. “Penalties and costs can quickly accumulate.”

This pile-on effect was particularly common with Indigenous offenders who accounted for 7.4 percent of all notices issued — “[a number] much higher than would be expected for a group that makes up just over 2 percent of the total NSW population,” the report noted. With many less likely to take the issue to court, it was found that nine out of ten Indigenous people failed to pay the fine within the set time frame and 45 percent of those notices were for swearing at police — an offence which was previously pursued far less frequently.

As was stated by the Ombudsman, “[This] resulted in much higher numbers of these recipients becoming entrenched in the fines enforcement system”.

Of course, these people are committing crimes and police have every right to serve punishment. But if that punishment puts them at proven risk of entering a cycle of poverty which leads to further crime, what’s the point?

As a measure to counteract this, the Indigenous Justice Clearinghouse has endorsed changes to criminal infringement notices, like more flexible payment options and alternative punishments, including mandatory community assistance. Among other suggestions, the Law and Justice Foundation of New South Wales has proposed fines which are instead proportionate to a person’s income.

But sometimes there’s an easier option. When a young woman is stealing tampons because she or her friend is embarrassed and/or doesn’t have the cash to buy them — and when you don’t have any legal obligation to slog her with the same fine you’d give to someone stealing a $400 stereo system — you could decide to give her a break.

–