Tony Abbott’s Biggest Problem Isn’t Trust; It’s Ridicule

If you've been anywhere near the internet lately, you've found an unprecedented deluge of parodies lampooning the Prime Minister -- in clips, memes, mash-ups and more. But what do they all mean?

In June last year, John Oliver’s Last Week Tonight featured a three-minute takedown of ‘President of the USA of Australia’ Tony Abbott – a searing and brutal appraisal, which coupled footage of Abbott’s various gaffes with a few snarky narrative asides. The clip, which has been viewed over 2.5 million times since, made the rounds among Australians of a certain age and political leaning.

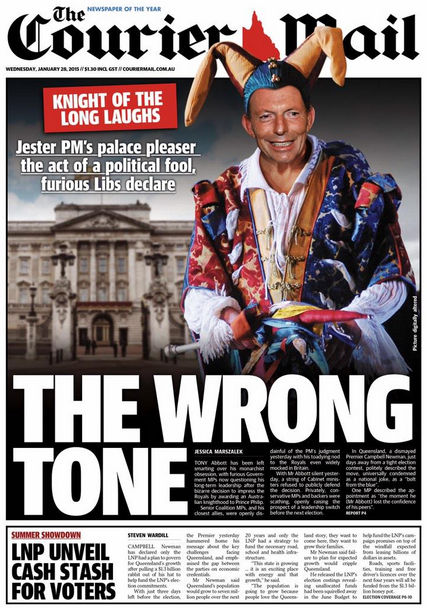

But with the infamous Prince Philip knighthood, ridicule of the Prime Minister burst suddenly and loudly into mainstream political coverage. Major papers across the country dubbed it a “knightmare”, while The Courier Mail grasped the unique opportunity to crudely cut and paste Abbott’s face onto a jester.

Huw Parkinson’s Four Weddings and a Funeral with Tony Abbott summed up Australia’s reaction pretty well.

Although being ridiculed by sections of the community his policies were alienating wasn’t new for Abbott, the ‘knightmare’ mis-step marked a distinct shift: now, he was being mocked by almost everyone in the country.

In fairness, it may not seem unusual, or worrying, for political leaders to be on the receiving end of this level of scorn. But for Tony Abbott it could become a big problem.

The Ridicule Rule

Saul Alinsky — famous for his work in community organising, whose tactics were employed by Barack Obama during his Chicago days of campaigning — well understood the power of derision. In his 1989 book, Rules for Radicals, he noted as rule five: “‘Ridicule is man’s most potent weapon.’ There is no defense. It’s irrational. It’s infuriating. It also works as a key pressure point to force the enemy into concessions.”

That the knighthood fiasco marked a tipping point in Abbott’s Prime Ministership — contributing at least in part to an exceptional LNP loss in Queensland, and the subsequent federal leadership spill — demonstrates this power. The issue also prompted a leap from ridicule as an oppositional weapon to ridicule as a natural response.

Northern Territory Chief Minister and Country Liberals Leader Adam Giles believed that the knighthood “[made] us a bit of a joke in a range of areas”; the formerly Abbott-sympathetic Daily Telegraph called it “ludicrous”, and even Rupert Murdoch weighed in on Twitter: “Abbott knighthood a joke and embarrassment.”

The Australian held back from direct criticism but stated in an editorial that, “with the odd decision to ennoble a member of the British monarchy, Mr Abbott gives those who would lampoon him a right royal charter.” Even Andrew Bolt called it “pathetically stupid”.

In his reflections on political life, failed Canadian opposition leader Michael Ignatieff makes much of the idea of gaining and losing your ‘standing’ within the community. To lose standing is to lose the ability to have the electorate bother to listen to what you are saying. Standing may be lost for any number of reasons, but the unique danger of ridicule for politicians is that while it can be indiscriminate and rarely generates deeper insight, it undermines authority with devastating effect.

Abbott dangles on the precipice.

The Abbott Effect

The Prime Minister’s major problem is that his gaffes are now forming a narrative, one that has broken through to the public consciousness.

Kevin Rudd, of course, had his “just fucking hopeless” moment, revealing underlying character traits that were familiar to some of his colleagues, like Tony Burke (“the chaos, the undermining, the temperament”) and Wayne Swan (who criticised Rudd for his “dysfunctional decision making” and “deeply demeaning attitude”). Yet this version of Rudd never seemed to capture the attention of the public, with his standing as preferred leader remaining high and his eventual return to the Prime Ministership actually boosting Labor’s electoral prospects.

In contrast, Abbott’s attempts to combat perceptions have tended to come unstuck. One such effort, through his self-appointment as Minister for Women and his support of a more generous paid parental leave scheme (at least until recently), has been undermined by comments on housewives and household budgets, as well as by awkward interactions unfortunately captured on camera. And in politics, as they say, perception is everything.

Mad As Hell’s Shaun Micallef’s explains the situation confronting Abbott: “I don’t know, though, whether we could have as much fun with [Malcolm Turnbull] as we could with Mr Abbott,” he told Junkee earlier this month. “He doesn’t seem such an extreme fellow. Anybody with an extreme view, right or left, is sort of more fun, I think, to deal with than somebody who is quite moderate.”

Ridicule of Abbott, then, has captured the zeitgeist in a way perhaps not seen since the presidency of George W. Bush. For the most part it retains its oppositional character, in line with Alinsky’s rule, though moments such as the knighthood demonstrate a wider willingness to mock the Prime Minister; even those uninterested in participating will admit that he sets himself up for it.

The result is a seemingly unprecedented amount of material aimed at undercutting a sitting Australian leader.

Parodies like All About Women’s ‘Minister for Men’, starring Gretel Killeen:

–

Or Baldino Industries’ ‘Tony’, which also hones in on his attitudes towards women:

–

Just last week, we saw the launch of another new web-series, ‘At Home With Tone’:

–

The Prime Minister’s combative nature, policy backdowns and apparent unwillingness to admit defeat have also led to numerous comparisons with Monty Python’s famous Black Knight: “It’s only a flesh wound!”

Meanwhile, the #ImStickingWithTony hashtag, co-opted by political opponents during the leadership spill, was so popular that it gained wider coverage. One in particular gave voice to the general sentiment:

#ImStickingWithTony for the lulz

— Asher Wolf (@Asher_Wolf) February 7, 2015

Abbott has also been slammed for his ‘Team Australia’ formulation, made international news for his “suppository of all wisdom” gaffe, and with ‘winkgate’ created his own ‘gate’ within a year of becoming Prime Minister.

Back-to-back interview flubs with morning show hosts Karl Stefanovic and Kochie didn’t help matters, making ridicule of the Prime Minister even easier.

When relatively mainstream shows such as The Project have decided that the mere mention of Abbott’s name is enough to generate a laugh, the result is a media environment and public mindset extremely difficult to navigate. To become shorthand for a punchline is to enter treacherous territory.

–

Can Abbott Recover?

As Peter Van Onselen notes, political leaders are able to endure disagreement and even hatred, “but when respect in the mainstream starts to be replaced by mocking … leaders find that their base starts to erode.”

Of course, all politicians face some degree of ridicule—it’s an unavoidable part of the job. But some instances stick harder than others.

Bill Shorten experienced his own special moment with his straight delivery of, “I haven’t seen what [Prime Minister Julia Gillard] said, but let me say that I support what it is that she said.”

Rudd was met with ridicule for ‘Ruddisms’ such as “fair shake of the sauce bottle” and his elaborate hand gestures (handily collated in gif form), and George Brandis copped it for his spectacular failure to define metadata. Yet none of these politicians appeared to lose their standing with the electorate as a result: they were seen as either one-off gaffes or low-level misdemeanours.

UK Opposition Leader Ed Miliband is another politician who is dogged by ridicule no matter what he does — a factor that has led some to argue that the electorate no longer pays attention to him. In this, Miliband provides possibly the best contemporary point of comparison to the Prime Minister.

With Abbott already in a similar position to the hapless UK Opposition Leader, after last week he is even worse off. Restoring trust is only part of what he needs to achieve. He also faces the far more difficult problem of getting the electorate to actually take him seriously.

On the Prime Minister’s recent claim that “good government starts today,” Laurie Oakes nails it: “It was a truly dopey statement, not only confirming the widespread view that good government had been lacking in his first 16 months as Prime Minister but also leaving him open to ridicule every time something else goes wrong.”

Judging by the immediate aftermath of this month’s spill—including confused frontbenchers, Kim Jong-il submarines, and holocaust jobs—the odds don’t look particularly good.

–

Scott Limbrick has written for Meanjin, Voiceworks and G20 Watch, and tweets from @ScottLimbrick.