Should You Make Like Mark Zuckerberg And Wear The Same Thing Every Day?

Mark Zuckerberg, Barack Obama and Steve Jobs have all done it. Will throwing out your glad rags make you more productive?

Check out Social Overlord Mark Zuckerberg, always wearing the same grey T-shirt and charcoal hoodie. You don’t need a facial recognition algorithm to know who he is.

Recently Zuckerberg did a Q&A at Facebook headquarters and was asked why he always wears the same grey T-shirt. He answered: “I really want to clear my life to make it so that I have to make as few decisions as possible about anything except how best to serve this community. […] I feel like I’m not doing my job if I spend any of my energy on things that are silly or frivolous.”

This was a pre-approved question, and Zuckerberg answered it in a PR-friendly way that flatteringly suggested his dedication to helping others. If choosing clothes is a method of communicating one’s personality to the world, then claiming to deliberately opt out of that choice seeks to evoke the humility practised by men and women who take Christian and Buddhist holy orders.

But Zuckerberg is not a monk with a spiritual or charitable vocation. He is the head of a profit-focused capitalist enterprise, and so his identical grey T-shirts communicate that Facebook’s profits aren’t spent on conspicuous displays of personal wealth; rather, they are thriftily squirrelled away for shareholders.

So, why do people like him wear the same thing every day?

–

Choice Paralysis And Decision Fatigue

“You’ll see I wear only gray or blue suits,” Barack Obama told Vanity Fair journalist Michaell Lewis in 2012. “I’m trying to pare down decisions. I don’t want to make decisions about what I’m eating or wearing. Because I have too many other decisions to make.”

In Aesop’s fable ‘The Fox and the Cat’, the clever fox has many ways of evading predators, while the cat has only one – but when the hounds approach, the fox freezes in indecision and is caught. The moral: “Better one safe way than a hundred on which you cannot reckon”.

Psychologists call this phenomenon ‘decision fatigue’ or analysis paralyis, and it was popularised by Barry Schwartz’s 2004 book The Paradox of Choice. Faced with many potential choices, our decision-making processes slow down to the point where action is never taken. We may have more freedom of choice than ever, but we’re unhappier for it.

Also gaining mainstream currency is the notion that too many choices create such cognitive friction that we make bad decisions later in the day. The idea that we each have a limited daily ‘reservoir’ of logical and irrevocable ‘decisions’ is key to the notion that we should eliminate some of the low-level ones – such as what to wear.

But when Fast Company journalist Rachel Gillett decided to wear the same clothes every day, it didn’t improve her creative thinking. “What I started to realize throughout this experiment is how much I appreciate variety over efficiency and how plans rarely go as you anticipated,” she reported. “After a few days I began to resent the black T-shirt and jeans I wore each day and daydream about the bright pink shirt or the polka dot dress I would wear next week.”

–

Tech Culture And The Neoliberal Bro-Cult Of Productivity

There’s something rather monkish and self-denying about tech culture, which seems to prize a strictly utilitarian approach to squeezing life for maximum efficiency. ‘Life hacks’ are theoretically about freeing you from everyday drudgery, but they really only free you to ‘be more productive’ – that is, to do more work.

Wearing identical clothes each day comes from the same neoliberal impulse that seeks to replace the frivolity of eating with a grey slurry known as Soylent. In this cult of productivity, pleasure is wasteful because it’s a goal in itself rather than something instrumental. No wonder Mark Zuckerberg thinks it’s “silly or frivolous” to choose clothing each day to delight the eye, cosset the body or lift the mood.

The idea that a tech leader should care about what he (and it’s almost always a ‘he’) achieves, not how he looks, also can’t be distinguished from a geeky defensiveness about physical appearance. Nerds have always been mocked in mainstream culture for dressing badly, whether it’s their high pants and pocket protectors, their Mountain Dew-stained T-shirts or their Adidas slides worn with socks. See this helpful geek timeline, for instance.

Tech culture’s well-documented hostility to women also can’t be ignored here. Caring about clothes is belittled because it’s feminised – something only silly women trouble their little heads with. But as Miranda Priestly (Meryl Streep) acidly schools her new assistant Andie (Anne Hathaway) in The Devil Wears Prada, “You’re trying to tell the world that you take yourself too seriously to care about what you put on your back … and it’s sort of comical how you think that you’ve made a choice that exempts you from the fashion industry when, in fact, you’re wearing the sweater that was selected for you by the people in this room from a pile of stuff.”

–

It’s Not A Uniform – It’s A Costume

Many people liken the experience of ‘wearing the same thing every day’ to wearing a school or work uniform. But that completely misunderstands what uniforms signify: membership of a group, with distinguishing features signifying status within that group.

When Interstellar director Christopher Nolan was recently profiled in The New York Times, writer Gideon Lewis-Kraus observed:

“He long ago decided it was a waste of energy to choose anew what to wear each day, and the clubbable but muted uniform on which he settled splits the difference between the demands of an executive suite and a tundra. The ensemble is smart with a hint of frowzy, a dark, narrow-lapeled jacket over a blue dress shirt with a lightly fraying collar, plus durable black trousers over scuffed, sensible shoes. In colder weather, Nolan outfits himself with a fitted herringbone waistcoat, the bottom button left open. A pair of woven periwinkle cuff links and rather garish striped socks represent his only concessions to whimsy or sentimentality; they have about them the sweet, gestural, last-minute air of Father’s Day presents.”

Nolan’s dress may be routinised, but it’s peculiar to Nolan. The strictly utilitarian explanations of ‘wearing the same thing every day’ ignore that people who wear the same thing every day don’t all dress alike. It’s not a uniform – it’s a costume.

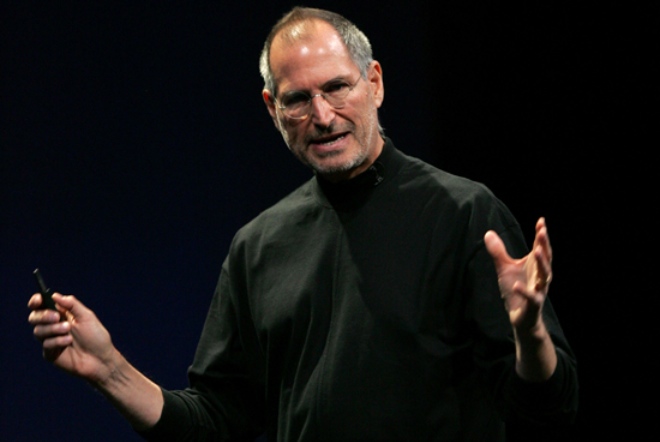

Steve Jobs is often counted as a precursor to Zuckerberg in sartorial consistency because he always wore black turtlenecks and jeans. But he reveals the difference between a uniform and a costume.

As Jobs’ biographer Walter Isaacson recounted to Gawker, Jobs was inspired on a trip to Japan where he noticed that Sony employees all wore uniforms – a cool black nylon jacket designed by Issey Miyake, which could unzip into a vest. The company’s chairman Akio Morita explained to Jobs that Japan’s uniformed culture arose after WWII, when clothes were in such short supply that employers had to provide them. Eventually, they became signature styles that enabled workers to bond to the company.

“I decided that I wanted that type of bonding for Apple,” Jobs later recalled. “I came back with some samples and told everyone it would great if we would all wear these vests. Oh man, did I get booed off the stage. Everybody hated the idea.”

But Jobs remained friends with Issey Miyake, who made him “like a hundred” of the turtlenecks that would become a personal signifier. Jobs was an intensely ambitious and arrogant man focused on building Apple’s business, but the turtlenecks created an impression of a retiring ascetic.

It’s an impression Mark Zuckerberg is no doubt keen to echo.

–

Mel Campbell is a freelance journalist and cultural critic. She founded online pop culture magazine The Enthusiast and is author of the book Out of Shape: Debunking Myths about Fashion and Fit. She blogs on style, history and culture at Footpath Zeitgeist and tweets at @incrediblemelk.