What Does Glorifying The ANZAC Myth Say About Our Attitudes To Violent Men Today?

When we say 'lest we forget', we choose not to remember some very uncomfortable things.

It’s ANZAC Day once more, and the public holiday hasn’t got any less controversial in the two years since this piece was first published.

—

We’re in the third year of the “centenary of ANZAC,” and there are two more to go. According to Carolyn Holbrook, ANZAC Day historian, Australia is spending more on commemorating this five year centenary than the UK, France, Canada, New Zealand and Germany combined. The $500 million centenary splurge is just the latest in a long, unbroken string of commemorating that has seen ANZAC Day overwhelm Australia Day as the de facto national holiday. Over the last few years, we’ve been urged by everyone from Prime Ministers to AFL clubs to Woolworths to recognise the overriding importance of those three iconic words: ‘lest we forget’.

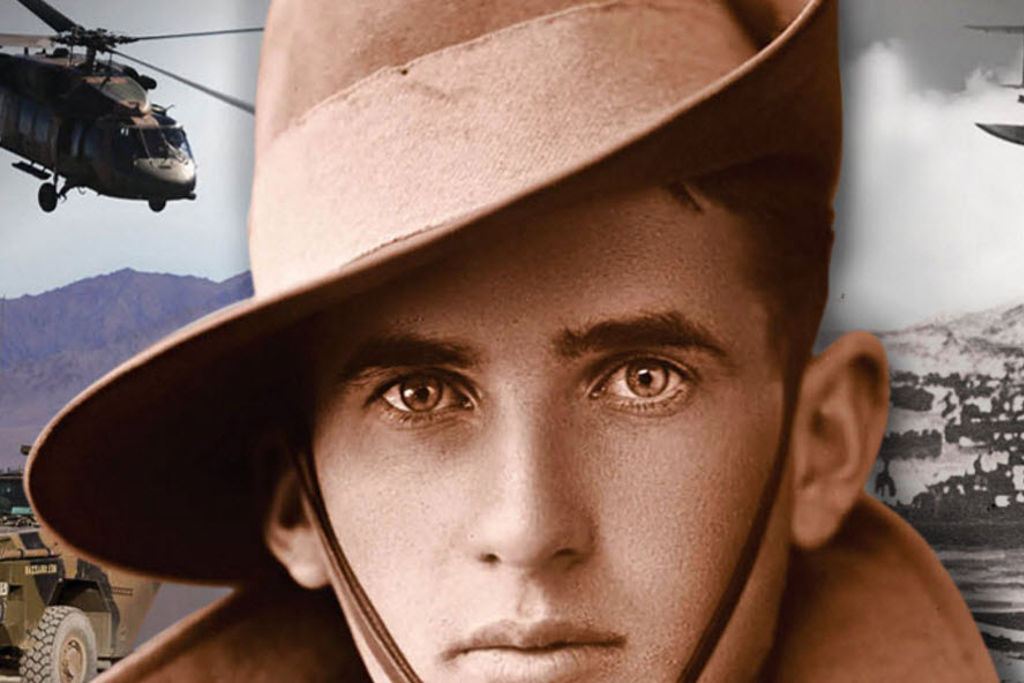

Conspicuously absent from this story we’re supposed to recall and reflect on, however, is the violence that Australian soldiers did. It’s hard to remember, among all the platitudes of sacrifice, that the smooth-faced young man staring soulfully down the lens of a camera from the early days of last century was trained to kill. The things we asked him to do for us were things that, if he did them to another Australian at home, would be called assault or murder.

The Ode of Remembrance, read on ANZAC Day and other historic military occasions like Remembrance Day, contains the twin injunctions: “age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn”. But it’s only possible for soldiers to escape condemnation if we deliberately forget the things they are sometimes required to do on our behalf — things like the Surafend massacre, for instance, in which 200 ANZAC troops razed a Bedouin village in Palestine to the ground and murdered between 40 and 120 of its inhabitants. It takes some sophisticated ethical gymnastics to think our collective military past is one only of tragedy and magnificence, and this act of forgetting conceals the dark heart of the ANZAC myth – that a culture so obsessed with the veneration of soldiers has never been able to contain or isolate the violence that soldiers do.

But as the violence required of men in war is airbrushed out of the story of ANZAC, violence against women is becoming more conspicuous in Australian public life. What if these apparently different kinds of violence – soldiering and family violence – are related?

Glorifying Violence, Forgetting Its Victims

Former Chief of Army Lieutenant General David Morrison’s Australian of the Year award in January ruffled some feathers, partly because he expressed an intent to keep up the work started by his predecessor Rosie Batty in pushing for action on domestic violence in his acceptance speech, while making no mention of veterans’ welfare.

But the work Morrison is doing to highlight violence against women is explicitly connected to the problems he sees within the military, and the detrimental effect they can have on both men and women who serve. In his 2014 White Ribbon Day speech, he acknowledged that the “hyper-masculine environment” of the armed forces had normalised the rape of women in the military by their male colleagues. He explicitly connected the culture of silence around rape in the military to the conjoined acts of remembering and forgetting:

“[M]any Australians now have an idealised image of the Australian soldier as a simple country lad – hair gold, skin white – a larrikin who fights best with a hangover and who never salutes officers, especially the Poms.

“Where do women, or Indigenous soldiers, fit in that narrative? They don’t and so, over time, such stories become myths and then myths become legends and then they become some unalterable truth.”

Here Morrison echoed the work of Marilyn Lake and Henry Reynolds, who argue that the lionisation of Australia’s war record — or the state-sanctioned killing of foreigners by Australian men — has obscured Australian women and migrants as well as other great civic and democratic Australian achievements.

But for Morrison, there is a darker consequence to the normalisation of violence as the province of ‘real men’. Since leaving the Army, Morrison has become a director of Our Watch, an organisation working to address violence against women. In that capacity, he said last year that violence imperilled women at home in the same way it did soldiers in the field, and that victims of domestic violence should be honoured and remembered as well as soldiers killed in battle.

In 2014, Morrison noted that even if we were not silent about domestic violence, the central space war commemoration occupies in our cultural landscape would still marginalise its victims. Stories of ANZAC:

“…are buoyed by aspects of our national culture in a way that makes it very hard for men to resist the pressures to conform to some distorted masculine image. It is a national culture that sees, in the wake of a terrible incidence of domestic violence … media reports that focus on how hard his life had become; how much he had been a loving man even in the act of murder.”

Bringing The War Home

This mindset has been part of the ANZAC myth since its very inception. Elizabeth Nelson is a historian who focuses on domestic violence cases following the Great War. She recounts the story of William O., who shot his wife in the neck in an Elsternwick street in 1922 when she told him she wanted a divorce. He was sentenced for only two years, for intent to cause grievous bodily harm. The charge of attempted murder was withdrawn on the basis of war service that had traumatised him. His wife, still marked by powder burns and with the bullet still lodged in her neck, spoke in his favour at his court hearing.

The problem is that William O. was never in the war – he was discharged as unfit for service with varicose veins. He had deserted after enlisting, and spent months in hospital recovering from VD. But he was a traumatised soldier, so nobody could blame him for nearly killing his wife.

Nelson has found hundreds of examples of “nerve-shattered” soldiers in the interwar years killing or grievously wounding their wives, and attracting lenient sentences and public sympathy. Nelson points out that “in some domestic violence cases the damage that the women sustained, such as bullet wounds and shock, was no different to that sustained by soldiers in battle”. Soldiers literally brought the war home with them. Morrison’s injunction that we also remember women who have died as a result of domestic violence starts to look compelling.

The ANZAC myth ensures that our focus remains on the perpetrators of violence, never its victims. ANZAC makes violent men into victims of violence, dying, sacrificing or “falling,” rather than perpetrators, killing. Since leaving the Army, Morrison has continued to make this point, and he is not alone. David Pocock was driving at this idea when he said of ANZAC Day that “whilst it’s good to remember the people who have died serving Australia, it’s equally important to remember people who died fighting against Australia”. Historian Joanna Bourke bade us remember that “the characteristic act of men at war is not dying, it is killing”. And as Bill Gammage reminded us, some soldiers even enjoyed killing, speaking of “[t]he bloody gorgeousness of feeling your bayonet go into soft yielding flesh” in their letters home.

We must not forget how often soldiers’ violence took on a gendered quality, as in the “Battle of the Wazzir,” where drunk ANZAC troops ran amok in Cairo, destroying brothels and targeting the women who worked in them in an imagined reprisal for the VD epidemic that plagued the First AIF. The act of remembrance is always also an act of forgetting. In the case of ANZAC, to venerate soldiers we must forget that they are killers, trained and sanctioned in the use of violence.

Perhaps if we remember instead that war is historically men killing, with state sanction; perhaps if we reflect on the ways in which the ANZAC myth normalises the violence that permeates our society; perhaps if we call out the ways in which we excuse and enable the mostly male perpetrators of violence through myths of magnificent sacrifice, we might be able to have some solidarity with the victims of violence, too frequently women, instead of with its perpetrators. If war remains the cherished heart of our national myth, we will remain inured to violence perpetrated by men. After all, what else is war?

–

Nick Irving is a modern historian who has written for Drum Unleashed and New Matilda, and can be found on Twitter at @nickrirving.

–

Feature image via ANZAC Day Commemoration Committee.