How Western Sydney Is Being Left Behind By Progressives

This is all more complicated than it looks.

On what should have been one of the most relieving days of this whole postal survey mess there was a blight; a big, fat reminder that despite the progress we’ve made, there’s still a long way to go.

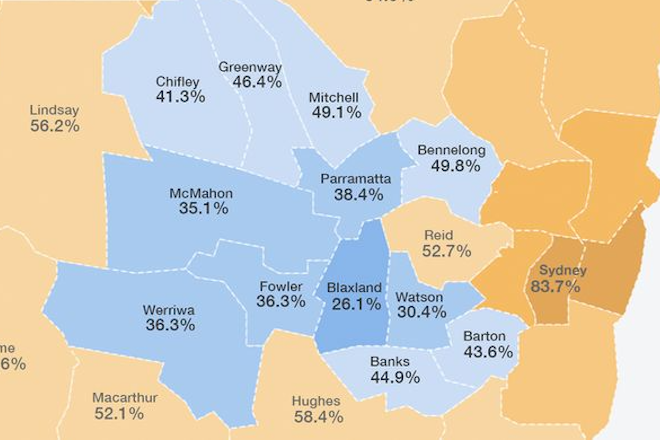

The reminder came in the form of a grouping of around 10 electorates in Greater Western Sydney, between Watson in the east and McMahon in the west. All are “safe” Labor seats. All voted emphatically No to marriage equality.

I grew up in Punchbowl, in Sydney’s west, and I currently live in Parramatta — one of the electorates that voted No. This result hurts. And for those who live and grew up here, like myself and many of my friends, and for the many members of Western Sydney’s LGBTIQ+ community, this week’s result left us with only one feeling: that we don’t belong.

But even though we feel that sense of frustration, most of the analysis being written about Western Sydney in the aftermath of the postal survey result has been disappointingly shallow. Largely because it’s been written by people who rarely, if ever, step foot in Western Sydney.

Let’s Ditch The Lazy Stereotypes

Immediately after the result was announced, the hot takes arrived. Western Sydney has a higher population of religious people, of people from non-English speaking backgrounds, of older migrants. These people don’t understand social justice and human rights, they said (essentially erasing the reason many migrated to begin with). That’s why they voted No. They aren’t representative of the “real” Australia.

The knee-jerk reactions were predictable. The Sydney Morning Herald wrote definitively about “the conservative values of immigrant cultures”. In The Daily Telegraph, everyone’s favourite commenter on race and politics, Mark Latham, wrote that, “The most valid explanation of the Western Sydney result is ethnicity”, squarely pinning the result on migrants. Journalist Mike Carlton called Western Sydney the “Bible and Koran belt” on Twitter. NSW Senator David Leyonhjelm said the result showed Australia needed to be “picky” about what kind of migrants it allowed.

Many of the 17 electorates that returned a majority No vote were areas with a high Muslim population in south-west Sydney. Surprise surprise #SSM2017

— Caleb Bond (@TheCalebBond) November 14, 2017

The strongest "no" electorate, Blaxland in NSW is held by Labor's Jason Clare. 29% of the population there is Islamic. Strong 'no' vote in Western Sydney correlates with large migrant populations.

— Nick Harmsen (@nickharmsen) November 14, 2017

Overwhelmingly it was white journalists and pundits who long moved out of the area, or never lived there at all, who led the conversation. “How could this “culturally diverse” place that consistently votes for centre-left candidates be so bigoted?” they asked in shock.

If any of the mainstream media outlets happened to have more diversity on their books, there’s a strong chance these analyses may have been more in-depth and nuanced. And, in fact, the responses from people from culturally diverse backgrounds have been far more impressive.

Trying to understand how the postal survey played in areas like Western Sydney is absolutely a valid question, as is asking how 38 percent of the country voted No. The problem so far has been the fact that the supposed answers have fallen into common and lazy stereotypes, rather than providing anything useful to us going forward.

Indeed, the rhetoric appeared to boil down to: ‘Western Sydney is full of non-English speaking, Bible and Quran-thumping nonnos and nonnas.’

But there’s a broader issue at play, one that relates to the marriage equality campaign but goes deeper: many residents of Western Sydney feel ignored completely by progressive politics.

Progressive Campaigns Don’t Look Like Western Sydney

As someone who grew up in Western Sydney and still lives there, I often feel like an outsider for my progressive views. When I used to be a Greens member, the make-up of local meetings never looked like the broader area: they were always white, mostly older men and women.

It doesn’t help that when you look at the Labor candidates that are fielded in the area, most are the type of career politicians contemporary society widely derides: Jason Clare, Chris Bowen, Tony Burke. These are people who don’t feel like a proper representation of Western Sydney.

There are cases when progressive causes chime strongly with people in Western Sydney: views on access to healthcare and education, the fight against Badgerys’ Creek Airport, views on the rights of Palestinians, as well as the success of politicians like Jihad Dib and Linda Burney. But they are the exception to the norm.

More often than not, there is a significant inability to communicate the key arguments for socially progressive issues, including marriage equality. Meanwhile, in the absence of genuine dialogue from progressives, conservative arguments are left to spread unabated.

These aren’t just older parents and grandparents who are sceptical of progressive politics. It’s also young people. They’re the guys at the gym joking about how one of them looks “so gay” for wearing a tight shirt. They’re the young men who think a banner showing the coach of an opposing team giving fellatio is “a joke”.

Even if many second- or-third-generation Australian millennials from Western Sydney call themselves agnostic, secular, or atheist, they often have those views on homosexuality (and sex, and women’s rights, and countless other issues) ingrained into them by their families, friends, churches, and other institutions. Point is: it starts young.

yes, the western sydney / migrant 'No' outcome is disappointing, but there were people – lots of queer POC – doing the hard yards in migrant outreach that didn't have anywhere near the institutional support of the upper-class gala hosting elite in the eastern suburbs

— sad-inista :( (@prafxis) November 15, 2017

Yes, religion plays a role. The electorates within Western Sydney do have higher rates of religious followings than other comparable electorates and the national average. But this alone doesn’t explain the strength of the No vote. It’s not just religious beliefs that drive conservative thinking. Rather, it’s in the ability for these places of worship to organise and congregate communities. To hold events that bring in and speak directly to families. These occur around here on a weekly basis. It was all too easy for the No campaign to piggy-back off them.

It’s difficult to find a way to counter this. But part of the problem, in my opinion, is how political campaigns — especially those for progressive causes — are currently run. Too much focus is placed on retention of votes, rather than converting new voters. Focus on the guaranteed supporters, and forget about the rest.

Undecided voters are left behind at best, and grow to resent the progressive cause at worst.

This can be a winning formula: it’s how the Yes vote won today’s postal survey in the first place. But the side-effect is that undecided voters, who may be getting conflicting messages from both their inner-city office mates and their more religious extended family, are left behind at best, and grow to resent the progressive cause at worst. With a bit more time and a few more conversations, the Yes campaign could have broken through to these voters. But that wasn’t the end-goal.

It’s these voters that the Coalition for Marriage targeted: the apathetic who were even the slightest bit sympathetic. They knew they needed a significant uptick in votes, so they worked hard on conversion. They were handing out leaflets in several languages, organising regular talks at religious gathering, and holding events in Fairfield.

They muddied the waters with talk of other laws and programs being “snuck in” with the vote. They used the fact that the Yes campaign was being driven by unfamiliar, white, upper-middle class faces and politicians against them.

How Campaigns Can Change Minds

Looking back, I can think of few times, if any, when the debate around marriage equality actually engaged with people from Western Sydney above a macro level. It often felt that, while myself and countless other Western Sydney residents were having conversations in the community, leafleting, and door-knocking, the wider campaign left us out to dry.

The only other major talking point that grabbed the attention of anyone west of Strathfield was if Macklemore would be allowed to perform ‘Same Love’ at the NRL Grand Final, which says a lot about how effective the campaign was in hindsight.

And the thing is, there’s a lot of positives that could have been brought forward. There should have been more materials in other languages. There could have been a discussion about how the country’s many families in Sydney have fled also share regressive views on gender and sexuality.

Instead, we’re left worrying endlessly for my queer pals, especially queer people of colour, in Western Sydney. Many have expressed sadness and grief at the result here, a literal affirmation that their community doesn’t care for them. If anyone deserves protection and warmth during these times, it’s them.

Albert Santos is a Sydney writer. You can find them on Twitter here.