We Spoke To David Sedaris On Growing Up, His Australian Tour And The Spoken-Word Renaissance

We didn't freak out internally during this interview, nope, not at all.

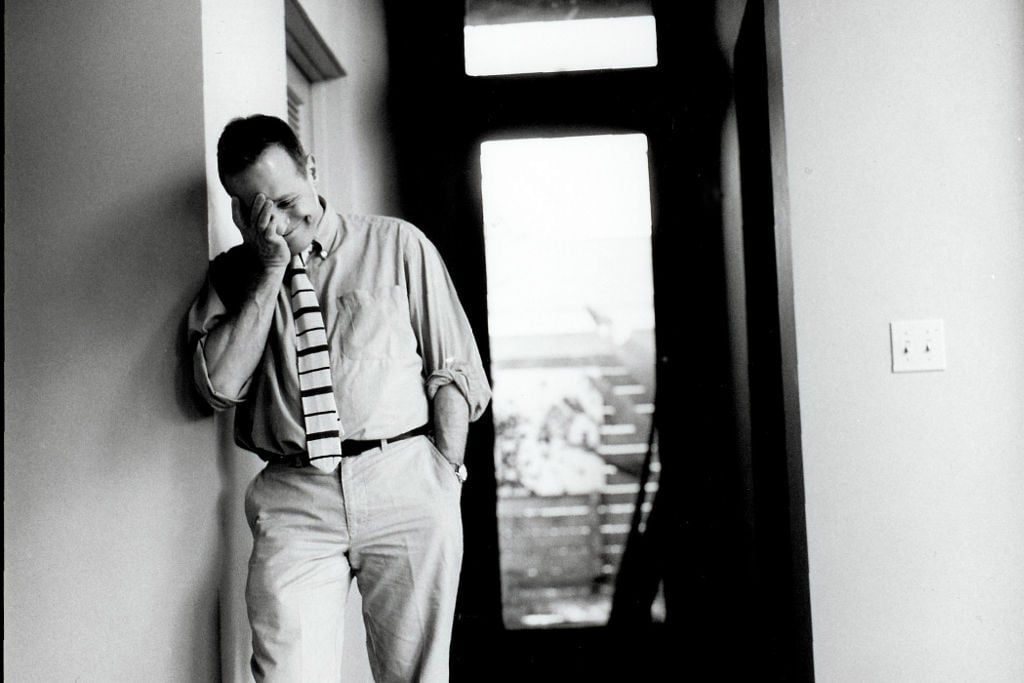

David Sedaris is an unlikely ambassador for the spoken word. He was hauled out of geography as a boy and sent to remedial lisp-correction, where instead of accepting the guidance of qualified speech therapist Chrissy Samson, he learned to avoid s-sounds altogether. In his own words, “‘yes’ became ‘correct’, ‘please’ became ‘with your kind permission’. Plurals presented a considerable problem, but I worked around them as best I could; ‘rivers’ became ‘a river or two'”.

Decades later, his North Carolina twang and upper register still make his listeners cock their heads. Salon called him “pleasingly strange”, and when I played a section of our interview to my mates and family (why? because I made him laugh. I made David Sedaris laugh. It’s saved in my phone as ‘Me-Induced Sedaris Laugh’), more than one person asked “is that your grandma?”.

But ambassador he is. He’s appeared on This American Life more than fifty times, been on international speaking junkets, released more than a dozen audiobooks, and is in Sydney at the moment on a reading tour.

Where did this affair with the spoken word begin? He arcs back to his childhood to answer this question, speaking to me from his Sussex home while (I am fairly sure) doing the washing up.

“I grew up in Raleigh North Carolina, which wasn’t a terribly big town. It was the capital, but it wasn’t exciting to me in any way. But there was a radio station in my town that played old radio shows, and I became conscious of that when I was in the fifth grade, and I would schedule my bath time around it. And that continued all through high school. I was always a big listener of people talking. When I was in high school every now and then the teacher would have people read out loud, let’s say Madam Bovary or something. And the teacher would call on people and I remember always thinking ‘Call on me. Call on me. Call. On. Me. I’ve got this’”.

–

Me Talk Pretty One Day: Reading Out Loud As A Job

It wasn’t until college that Sedaris got his wish, though, while he was at art school as a returned dropout. “I was like 27 when it happened. I was in a painting class and we had a critique, and you put your work up and talk about it, and most people would talk as if they were alone with a psychiatrist. It wasn’t the kind of thing that anyone would want to listen to,” he says.

“And one of the things that I realised was they don’t understand that we’re the audience. They don’t have any sense of an audience. For some reason, maybe it’s because I have so many brothers and sisters, I was always very acutely aware of an audience. So when my turn came the next week, I had written something that was like a little monologue, like a character who was giving reasons why his paintings worked. And people laughed, and it felt amazing to me. And then from that point on, I didn’t care about painting or sculpture any more. … I thought, ‘this is what I’m supposed to do. Write my own stuff and read it out loud’.”

Read it he has: you can get a box set of his audiobooks that contains 20 CDs. Bruce Springsteen’s entire studio discography is only 18. This is fitting, though. Sedaris’ work is meant to be read. When book promoters describe books as ‘readable’ it’s usually code for low-brow. Books are ‘readable’ in the way that Andre Rieu is ‘listenable’ or powdered mashed potato is ‘digestible’. Its highest aspiration is that you can do the one thing you should be able to do with it.

Sedaris’ work is readable in the proper sense: there is a rhythm to the prose, a percussive footfall to every comma and punchline that means it has a voice, not just an author. What’s the secret? Does he work by speaking or by typing?

“I feel like I used to write for me to read out loud and now I write so that anyone can read it out loud,” he says. “I feel like it’s right there on the page: slow down at the comma. Stop at the period. And I read it out loud to myself as I’m writing it, because the rhythm is important to me. Earlier, I could create rhythm if there wasn’t rhythm on the page. I could join two sentences together and create a rhythm if it wasn’t implicit on the page. But now it’s implicit on the page, so anybody should be able to do it.”

He’s accrued a decent amount of practice by reading this much to so many people: “when I look over early things that I wrote it seems so clunky to me. And I was reading them out loud once, and you learn a little bit reading something out loud once but if you read it twenty times you really learn.”

–

Podcasts, Audiobooks, And The Spoken-Word Renaissance

Not everyone gets the phenomenon. Sedaris ranks at #25 on StuffWhitePeopleLike.com, that hideous millefeuille of defensive irony and classism, where author Christian Lander and Least Surprising Candidate for Whitest Dude of All Time weighs in: “People go crazy and pay to hear him read from his own book. Let me say that again: people will pay to see someone read from a book they have already read.”

For me, at least, that’s part of the charm. David Foster Wallace used to describe reading as a way off the existential islands we make for ourselves inside our skulls. Listening does this tenfold for some of us: there is something essentially human breathed into prose by another person’s voice. For years I’ve fallen asleep to the sounds of exactly the same audiobooks — the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy; Stephen Fry’s Harry Potter; the adventures of Paul Temple, the BBC detective and his pillbox-hatted wife who say helpful audience-facing things like “imagine I know nothing whatever about the case, inspector”.

I’m in the middle of confessing this habit to Sedaris when he cuts in: “aren’t those just the best? When I can’t sleep I’ll just put one on, it doesn’t matter which one. Any of the books with Stephen Fry. I don’t mean his voice lulls me to sleep but it’s so good, I can listen to it over and over again like a child.”

The spoken word is such an essential part of Sedaris’ personal universe that he confesses to slight bafflement at so many people get it so wrong, so often. “I was amazed when other people couldn’t read out loud,” he says. “I don’t mean people who were dyslexic, I mean — you know sometimes, here in the US, there’s National Public Radio, but there are commentators and reporters who have no idea how to read a sentence or where to put the emphasis — it’s almost like they’re reading something phonetically in Korean. ‘I believe… that children ARE! .. the future’, like how can you not know? I guess they’re just tone deaf people. It can be horrifying when somebody reads to you what you wrote.”

Does he think there’s hope for these people? “I think people can teach themselves. I think it’s like a lot of things, if you’re interested in it you can teach yourself. But I don’t know that if you had a room full of people you could teach them. I think only the people who were truly interested would learn. But don’t you think it’s like that with everything? Like when I went to art school, it’s kind of a sham, really. Because the only people who are really going to learn are driven to learn, and they’ve got something inside of them that says they want this. But if you don’t want it, then it’s not going to work”.

It seems that a growing number of people do want it. The spoken word is at its highest moment of saturation in popular culture since the days of whole-family listening around a real radio in a dining room, like a physical incarnation of what you’d get if a radio manufacturing company sponsored a Norman Rockwell sketch. Last year Serial set a new watermark for what counts as a successful podcast, hitting five million downloads on iTunes and launching spinoffs and spoofs galore.

Audiobook sales have doubled in the last five years, pushing the movement a long way from Sedaris’ first memories as a child in North Carolina: “When I started listening to audio books, in the beginning they were just for blind people. And in the United States people listen to them while they drive. And now it’s people who exercise. So it went from blind people, to people with long commutes, to people who are fat”.

Which adds up to quite a lot of people, or so say the audience figures: Audible adds over 1,000 titles a month and is growing fast. In the last year, the publishing industry has started using “the Netflix model” to make new material designed to match the medium, like full-cast dramatisations designed to be spoken instead of printed.

Sedaris might be an unlikely ambassador, but an ambassador he is. You can catch him in Sydney for his reading tour, but be warned, when I asked what he noticed about Australian audiences he told me “I love that you can ask anybody there what they paid for their house, and they’ll tell you.” Go to see him, but go with your property appraisal in hand.

–

Information for David Sedaris’ Australian tour is as follows:

NEWCASTLE

Venue: Civic Theatre, 375 Hunter St, Newcastle

Date: 7:30pm, Sunday January 17

Bookings: ticketek.com.au

SYDNEY

Venue: Sydney Opera House Concert Hall, Bennelong Point

Dates: 7:30pm, Monday January 18 & Tuesday January 19

Bookings: sydneyoperahouse.com

BRISBANE

Venue: Brisbane City Hall, 64 Adelaide St

Date: 7.30pm, Wednesday January 20

Bookings: ticketek.com.au

MELBOURNE

Venue: Hamer Hall, Arts Centre Melbourne, 26-28 Southgate Ave, Southbank

Dates: 7.30pm, Thursday January 21 & Friday January 22

Bookings: ticketmastercom.au

HOBART

Venue: Theatre Royal, 29 Campbell St, Hobart

Date: 7.30pm, Saturday January 23

Bookings: theatreroyal.com.au

PERTH

Venue: Octagon Theatre, University of WA, Perth

Dates: 7.30pm, Sunday January 24

Bookings: ticketswa.com

–

Eleanor Gordon Smith teaches ethics and philosophy at the University of Sydney. Feature image by Anne Fishbein.