Now More Than Ever, We Need To Talk To Each Other About Mental Illness

We don't talk about it nearly enough - to each other, or ourselves - and that has to change.

If you suffer from depression, you can reach Lifeline 24 hours a day on 13 11 14.

–

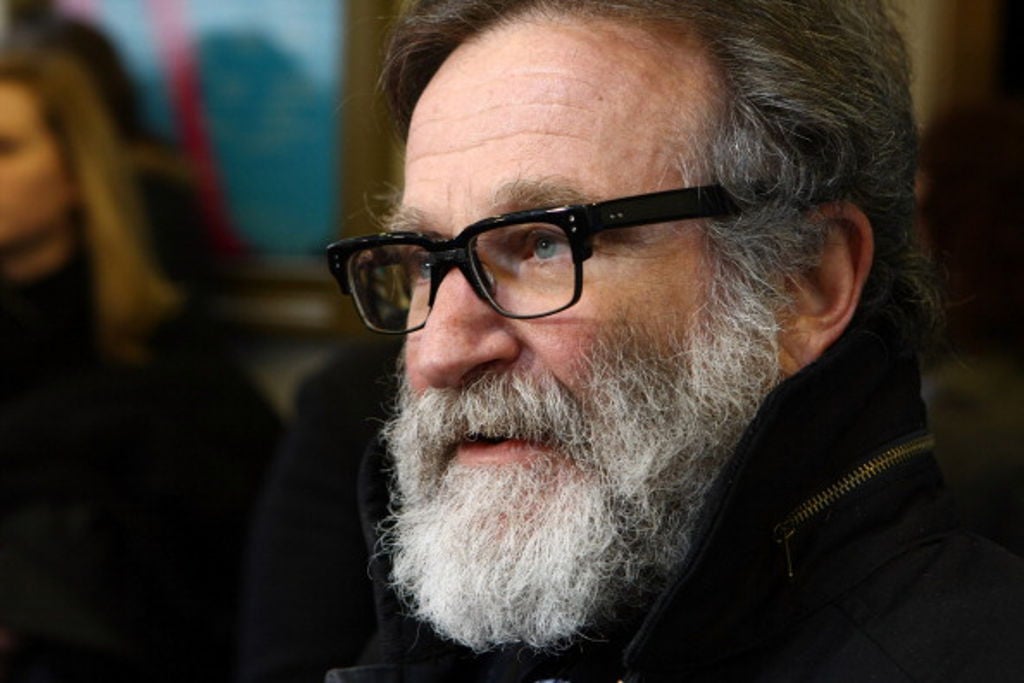

This morning, depression was once again thrust into the spotlight in the worst possible way, with the devastating news coming through from the US that beloved actor and iconic comedian Robin Williams has taken his own life.

It seems bizarre that a man who brought so much joy into people’s lives was unable to find lasting joy in his own, but anyone with depression can understand how such a seemingly impossible dichotomy can exist. I have depression, and around 178,000 people aged 16 to 24 in Australia do as well. At this point, it’s worth examining what exactly depression is, and — if you have it, or think you might — what you should do.

Depression is a very difficult thing to explain to people who don’t have it; partly because it’s different for everyone, but also because it describes an absence rather than a sensation. A common misconception is that depression is simply ‘feeling blue all the time’. It’s not, although it often leads to being down more often, and more severely. Williams said it best when he called it the “lower power”, the little voice inside that sees a bottle of Jack Daniels and goes “hey, just a taste”. In 2006, he described it to ABC News: “You’re standing at a precipice and you look down, there’s a voice and it’s a little quiet voice, that goes: ‘Jump’”.

He was right. Depression is not a feeling, of sadness or anything else; it is the sickly white glow of a laptop screen in the middle of the day. It is the hideous, blissful buzzing that fills the brain when hours of relentless scrolling through Facebook posts, Twitter feeds, news articles — something, anything — finally do their job and you slip into a waking trance, a self-administered anaesthetic. It is the telltale reek of a room that has been lived in too long; the hothouse fug of old sweat and unwashed sheets, and plates of food beside the bed. It is the grinning desperation behind the sixth beer. It is a sickly pressure under your ribcage that you can touch with your hands and feel the contours of, like an organ gone bad.

If the condition itself is difficult to describe, the effects are often all too tangible. Nine months ago, when I first walked into a doctor’s office and admitted I have depression, I was a wreck. I had been on a steady downward spiral for about three or four years that, on paper, reads like a mid-life crisis come twenty years too early. I had failed around a year’s worth of university subjects, lost two jobs, and almost gone bankrupt. I would spend weeks at a time not leaving the house and, as far as was possible, my room. I would often go days without changing clothes, or having a shower, or brushing my teeth. I retreated from my parents and my friends, and invented elaborate stories to hide my circumstances from them.

If this sounds like you, or it reminds you of someone close to you, that is a sign. At this point it can be difficult to know what to do; it can be a hugely painful thing to admit to yourself. But you must admit it, and you must act.

I was first diagnosed when I was seventeen, and I went badly wrong in assuming I could deal with it on my own. I thought, like a lot of people do, that the way I was acting was a sign of a defect in my character; some fundamental weakness that made me lesser than the people around me, and that I could overcome by just growing some stones and changing my attitude. I thought seeking medical help would be giving in to that weakness. It wasn’t until I could no longer pretend that I was coping, even to myself, that I went to see a doctor.

Now, first thing every morning — before breakfast, before a shower, before my eyes are even half-open — I take a little green-and-white pill that has been prescribed to me by a medical professional. Twenty milligrams of fluoextine hydrochloride in a spongy, easy-to-swallow capsule that I wash down with a glass of water before I start on my Weet Bix.

Six months since I started taking those little pills, I’m out-of-sight better than I used to be. I get up early; I drink less; I exercise more. I feel good, most days. I have my bad patches, but I don’t recognise myself from the person I was. My life as it is would not be possible had I not sought help.

I am still depressed. It is possible that I always will be. But those little green-and-white pills get me on my feet; they get me out of the house; they get me washed and dressed and into the day. They’re not perfect; they’re not a cure-all, and they’re not enough purely by themselves. But for me, they’re a hell of a start.

Maybe my little pills aren’t for you; maybe the thing that gets you there is something else entirely. But whatever it is, go find it. If you’ve been putting it off, don’t put it off anymore. Go to a doctor and tell them how you feel. Get a prescription, go to the chemist and fill it. Take your pills. If they don’t work, talk to a counsellor. Tell your friends, your family, anyone who can and will help you whenever and however you need them to.

If who know someone who is depressed, talk to them. Listen to them. Do not judge them, or reach conclusions for them, but let them know you are there for them. Recently a good friend confided that he has tried to kill himself a few times. I had suspected he was severely depressed, but I had never asked him how he was feeling, or if he was seeking help. Like me, he is now far better than he was, but it makes me shake to think how close I’ve come to needlessly losing someone I love. Nothing is worth that; no awkwardness, no uncomfortable silence.

A lot of people have been observing that if it can happen to Robin Williams, a man who devoted his life to the pursuit of joy and laughter, it can happen to anyone. They are right. No one is immune.

But no one is beyond help, either. I thought I was. My friend thought he was. But we are still here, better than we were, and hopefully on the way to being better still.

Say no to death. Say no to nothingness, and blankness, and silence. Get help. You are worth the saving, and life is worth the living.

–

If you suffer from depression, you can reach Lifeline 24 hours a day on 13 11 14.

–

Feature image by Neilson Barnard/Getty Images.