Natalie Portman Breaks Down ‘Vox Lux’, A Film About Pop Music And School Shootings

Chatting to its star Natalie Portman, 'Vox Lux' begins to make a little more sense.

Vox Lux might prove to be one of the oddest mainstream films of the year, in terms of both its plot and tone. But by the time I’ve finished chatting to Natalie Portman, it begins to make a little more sense.

— Content warning: This article discusses gun violence. —

On paper, Vox Lux isn’t so complex: directed by Brady Corbet, Portman plays Celeste, a mononymous pop-star who first catapulted to stardom as a thirteen-year-old survivor of a school shooting with ‘Wrapped Up’, a song that helped heal a nation. As the film’s narrator (Willem DaFoe) puts it, “It was not her grief. It was theirs.”

But we don’t see Portman on-screen until an hour has passed: the film is split in two parts, with Raffey Cassidy (The Killing Of A Sacred Deer) portraying Celeste in 1999-2001 as she preps her debut album post shooting, and Portman playing her in 2017, on the eve of a comeback concert. While this isn’t strange itself, the way Vox Lux straddles time is incredibly disorientating. It is by no means a smooth transition.

For starters, Portman takes over as Celeste while Cassidy double-times as her daughter Albertine, but Celeste’s sister (Stacy Martin) and manager (Jude Law) are untouched by time, looking the near same as they were in 1999.

Not to mention Celeste is near unrecognisable. Yes, Cassidy resembles a young Portman, but their posturing is wildly different, and it seems like little effort was made to match Cassidy’s soft-spoken Long Island accent with Portman’s hackneyed ‘New Yark’ one. Turns out, none was.

“Brady actually didn’t want us to coordinate because he really wanted us to go in as two completely different characters,” says Portman. “And so we met before [but] more about the mother-daughter connection… they’re supposed to be kind of estranged anyway, as mother-daughter. We didn’t have that much time together. It was incredible getting to see what she did with young Celeste when I saw the final film because I didn’t know any of that before.”

“I think she plays [the accent] up,” Portman explains. “I think it’s part of the toughness she has, and the armour that she builds around herself that lets people know that they shouldn’t mess with her.”

I tell Portman that need to establish roots reminds me of the way Lady Gaga has repeatedly, throughout her career, begun anecdotes with “I’m Italian, and I’m from New York”. Much like the A Star Is Born press junket, it’s a pastiche of authenticity, an exaggerated truth — and while Gaga’s ’99 people in a room’ line seemed to say something about our need for that performance, the film itself had an oddly judgemental relationship to what pop music can be and offer.

For those of us a little disappointed by Ally’s confusing character, Vox Lux‘s trailer promised something deeper. In it, Celeste embodies the troubled pop-star archetype — embodying empowerment on-stage yet screaming behind the scenes about being treated like a child.

Vox Lux asks what healing, if any, mass culture actually offers, and whether communal grieving is just a pantomime of trauma.

It evokes the great back-stage breakdowns of classic pop-star documentaries, like Gaga’s Five Foot Two or Madonna’s Truth Or Dare, both of which Portman watched in preparation.

“I took a little bit from each of them,” she says. “…There’s elements of the lifestyle that were really helpful to understand, like the way that the people you travel with can become like a family, and that a lot of people actually have their real family members become part of their crews, and [seeing] what that dynamic is like…. how you’re in a different city every day and how people treat you and how you kind of keep the persona on at all times.”

And while Celeste isn’t based off any one figure, it’s clear that Vox Lux plays with real-life: Celeste calls her fans “Little Angels”, and her music is penned by Sia (who also executive produced the film), including a song called ‘Firecracker’, surely a not-so subtle nod to Katy Perry’s ‘Firework’.

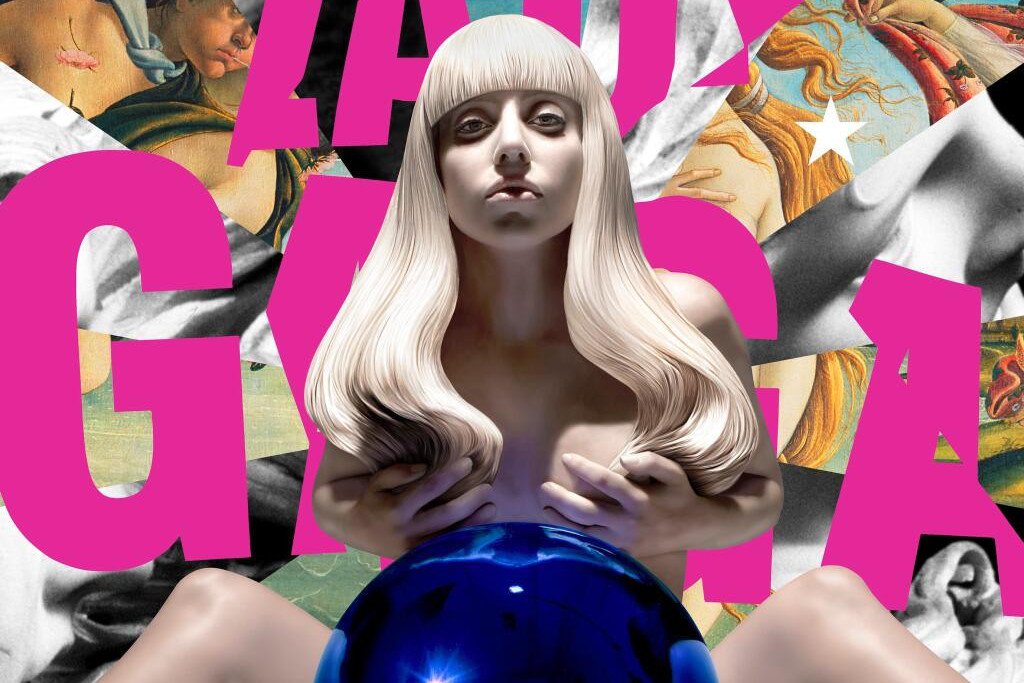

But with terror and national tragedy in the film’s foreground, it’s clear that pop music is merely a conduit to explore bigger ideas. And much like Lady Gaga’s uneven 2013 album Artpop, those ideas might prove a little too cerebral to pack in.

Still, it’s hard to not be engrossed as Vox Lux reaches towards them, and asks what healing, if any, mass culture actually offers, and whether communal grieving is just a pantomime of trauma.

‘All That Matters Is That You Have An Angle’

Vox Lux begins with an extremely bloody prelude of a school shooting, prompting comparisons to shock-auteurs like Lars Von Trier and Michael Haneke, both of whom Corbet has worked with as an actor. While my first initial thought after the prelude was that the film could have cut the bloodbath, its intensity lingers throughout.

Celeste has a bullet permanently lodged in her neck, and wears a series of braces, scarves and necklaces to cover up the scar. While residual trauma isn’t directly interrogated in Vox Lux, it is always present, albeit abjectly obscured — it is one of the few visual ties between the two Celestes.

Much like Lady Gaga’s uneven 2013 album Artpop, Vox Lux‘s ideas might prove a little too cerebral to pack in.

With the shooting taking place in 1999, it is analogous to the Columbine High School massacre, where 15 people (including the two killers) died. But the film’s tagline is “a 21st century portrait”: Columbine, the film seems to argue, has cast a long shadow.

“I think that these violent events are very particular to this moment in history,” Portman says, when I ask about the film’s tagline. “I hope that it’s going to change for the better, of course, but I think that terror attacks and school shootings are certainly a thing that we have happening [in extreme] now that haven’t really happened before like this, to this extent.”

Terrorism is being fought on two fronts in America, both of which feature in Vox Lux. There’s the external threat, and an internal one — an increase of mass shootings and violence, predominantly carried out by young white males.

“Brady framed it for me before I even read the script,” Portman said. “When we talked, he told me that his first film [The Childhood Of A Leader] was [set] between the First and Second World Wars and he was thinking, “What is the equivalent today?”. And that where he wanted to frame this between the wars he said were our wars now, which he was saying are these terrorist attacks and school shootings. So that was definitely interesting to hear before I even read it.”

In one scene, the adult Celeste links pop-stars and terrorists by their need for attention: “If you don’t give them any, they fade away”. I ask Portman about the line, as it arrives with weight.

“Well I think that it’s a comment on the spectacle of evil, which is so much what Brady’s talking about,” Portman says. “…That the audience gives the news story its power. How much attention you pay something makes it important or not, and you have to remember that power to limit how that puts these kinds of events in a spotlight that they don’t deserve.”

It’s a salient point, given that the media attention around Columbine encouraged copy attacks, as an overt focus on the how and the why unwittingly advertised the power of notoriety and turned the perpetrators into martyrs.

In wake of this, journalists are regularly criticised for turning male perpetrators into protagonists. Shooters become ‘loners’ rather than terrorists; sexual assaulters become young boys who have ruined ‘their promising lives’. In contrast, Vox Lux spends almost no time on the shooter’s motives — nor even the shooting itself, as it quickly moves into the pop sphere.

“[Corbet] wanted to frame Vox Lux between the wars he said were our wars now: these terrorist attacks and school shootings.”

In the film’s first half, Celeste is pushed into a series of situations way beyond her years, and we watch as the foundations of herself are mis-set. With little explanation for the time gap, we can see that adult Celeste has tried to recalibrate herself but remains permanently off-centre, addicted to drugs and absent as a mother. It is unclear if the pain predates the pop.

Still, pop music is presented as an antidote (or anaesthesia). “I don’t want people to have to think too hard, I just want them to feel good,” a young Celeste says about her own music. The idea’s echoed in the latter half’s comeback concert, a 10+ minute scene where Portman is mesmeric in a swirl of choreography, pyrotechnics and spectacle. It’s a reprieve, arriving as if it was lifted straight from Truth Or Dare.

Portman tells me she rehearsed hard and pushed her body for the scene, gaining a new respect for pop stars along the way. She was never too worried about her voice though: in a chat with Billboard, Portman revealed Corbet offered her the role before he’d heard her sing.

“He said it doesn’t matter, that’s kind of the point,” she said. “If you can basically carry a tune, they can do a lot of magic to make it sound like a great song.”

It’s true that autotune can fix a lot, but it also reveals how Vox Lux treats pop music like the world treats Celeste: an empty product on which to project meaning. It’s all wrapped up.

Vox Lux is in cinemas Thursday 21 February.

Jared Richards is a staff writer at Junkee, and he’s a private girl in a public world. Nonetheless, follow him on Twitter.