It’s Time To Give ‘Twilight’ Credit For Paving The Way For Female-Led Films

Ten years after its release, it's clear that 'Twilight' changed the way Hollywood thinks about movies marketed at women.

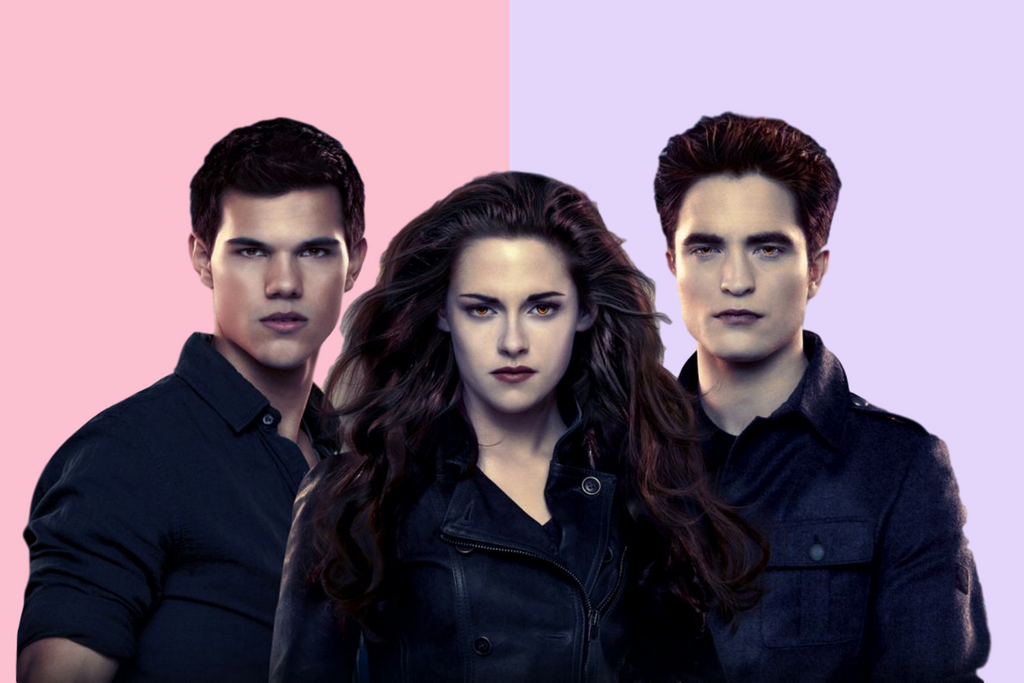

For a lot of women — and more men than would care to admit it — the question of ‘Team Jacob or Team Edward?’ was a pretty important one in the late naughts.

And it was all thanks to a best-selling novel series by Stephenie Meyer, which simultaneously solidified the Young Adult market as a formidable one in the publishing industry and affirmed the power of the female audience at the box-office, online, and at your local department store.

On the surface, it was a story about an ordinary teenage girl — played by Kristen ‘K-Stew’ Stewart in the films — who caught the eye of an immortal teenage vampire — played by Robert ‘R-Patz’ Pattinson — who, yes, occasionally sparkled. With gritty, indie filmmaker Catherine Hardwicke at the helm, the book-to-movie adaptation that hit cinemas in 2008 should have done just fine. It had a mid-range budget of $37 million and was supposed to be a little cult film that would maybe find its audience on home entertainment.

Instead, it became a $3.3 billion juggernaut of a franchise with five films, spin-off books, a loyal fanbase, billions of dollars worth of merchandising and an entertainment industry left scratching their heads about why they didn’t see this coming.

More Than A Sleeper Hit

“Here’s what seemed to go on for years,” says Empire Magazine journalist and pop culture commentator Helen O’Hara. “Every time there was a female-led smash it would be called a ‘sleeper hit’. ‘No one could have predicted that Devil Wears Prada, Mamma Mia or Eat Pray Love would be a hit!’ Each one would be written off as an unpredictable outlier. Twilight showed that female-led franchises could work and, in fact, that teen boys were now a less potent box-office force than teen girls.”

O’Hara and I originally met back in 2011, when the two of us travelled to the US for the annual pilgrimage of geek culture known as San Diego Comic Con. We got up at 6am to attend an exceedingly early (for Comic Con standards) press conference for The Twilight Saga: Breaking Dawn Part 1.

For the past four years, Twilight had seen women invade the previously male dominated spaces of pop culture conventions thanks to the global success of the movies and books. Because of that, Summit Entertainment — the film studio responsible — organised one of the biggest press conferences that year, shuffling in nearly a hundred print, online, and television journalists from all around the world into a room and locking the doors. Literally.

Unable to leave, over the course of three hours they wheeled out actor after actor: from those who barely had more than a few minutes of screen time like Booboo Stewart and Charlie Bewley, to the central trio of K-Stew, R-Patz and Taylor Lautner. To this day, it’s still one of the weirdest experiences of my pop culture journalism career.

As we left hours later, publicists from Summit were standing at attention outside the doors, handing out books for properties they were adapting next — Isaac Marion’s Warm Bodies, Veronica Roth’s Divergent, Erin Morgenstern’s The Night Circus — while maintaining unflinching eye contact and a smile as they chirped “this is the next Twilight”.

The five-film franchise wasn’t even over yet, but everything wanted to be “the next Twilight”. Just look at the graveyard of ill-fated YA movie franchises like Beautiful Creatures, Vampire Academy, The Host, The Fifth Wave, Fallen, Mortal Instruments and Divergent (which never even got to conclude).

From Star Wars to Batman, the biggest movies with the biggest fan bases command space in Hall H at San Diego Comic Con. As Clerks and Dogma filmmaker Kevin Smith reflects, Twilight was one of the first female-driven properties to fill that famous room. For some attendees, it was a shock to see a movie aimed at teenage girls bestowed the honour of Comic Con’s biggest room.

“Finally there’s some fucking women here and you’re gonna chase them out? Shut the fuck up.’”

“I was in Hall H the year Twilight was there at San Diego for the first time and there was a lot of bitchin,” he said on a recent episode of his podcast Fatman On Batman with Marc Bernardin.

“A lot of people were like ‘what does this fucking have to do with anything?’ and when I was on the Hall H stage I was like ‘um, number one, it’s vampires so it has everything do with this shit but number two, more importantly, it’s fucking girls you assholes! Finally there’s some fucking women here and you’re gonna chase them out? Shut the fuck up.'”

It was a classic case of the inherent misogyny and sexism that comes out when things women love get attention — something comic book artist and co-creator of the best-selling graphic novel Black Magick, Nicola Scott, couldn’t agree more with. Not only was she at San Diego Comic Con promoting her work for DC Comics in the years that Twilight swept the convention centre, she was also watching the impact it was having on a micro level.

“My niece was a key demographic — she was 12 when it came out, she’s 22 now — and Twilight just hit her right in the tits,” says Scott, “It was her favourite movie, she read the books 50 times, but she’s now a hardcore horror fan: that was her introduction to the genre spectrum.

“Twilight was the entry point for girls who I don’t think had been really considered up until then.”

By Women, For Women

It changed more than just the audience: behind the camera, Twilight was kicking in some doors. It was about a woman (Bella Swan), written by a woman (Stephenie Meyer), adapted for the screen by a woman (Melissa Rosenberg), produced by several women (Meyer, Karen Rosenfelt, Barbara Kelly, Marty Bowen, Michele Imperato, Kerry Kohansky-Roberts) and at least with the first — and best — film, which set the tone for the entire franchise, directed by a woman (Catherine Hardwicke).

Suddenly the female market wasn’t ‘niche’ anymore: if the right people made the right content for them, the female market was willing to spend and not just at the box-office. Tie-in merch counted for hundreds of millions of dollars worth of added revenue over the course of just a few years.

The women who made Twilight weren’t content with easing back on their newfound power once the movies went away. Rosenberg used her capital to adapt Jessica Jones from comic book to television for Netflix, it becoming one of the most overtly feminist and nuanced female-driven shows ever. Meyer started her own production company, funding and developing other women-targeted properties for the screen such as Austenland with Keri Russell, The Host, Down A Dark Hall and The Storytellers initiative, which saw all-female writer and director crews create short films officially set within the Twilight universe.

That’s not to mention what the stars of the franchise of themselves have gone on to do. “It’s given us the extremely interesting and daring careers of Kristen Stewart and Robert Pattinson, which is a great result,” says O’Hara. “I think it empowered a string of direct descendants in The Hunger Games and Fifty Shades, and all the rest, and got a lot of women in meetings they would not otherwise have landed.”

Among all the splendour of storytelling, it’s easy to forget Hollywood is still a business and because of its monetary success, Scott says Twilight had a lasting impact.

“It was the first time a girl property — that was also a genre property — came out of nowhere,” she says. “No one thought it was going to make much money … then it made all the money. When it comes to the films and television shows, female stories is where the mainstream is at the moment because that’s where the money is being made.”

That’s not to say the effect Twilight had was all positive: suddenly there were love triangles being shoehorned into everything, not to mention the mostly white and straight cast of characters at the foreground of the story, the often abusive power dynamics between Edward and Bella, and the fact it was a celibacy parable after all.

“I don’t think it massively tipped the feminist scales as we might have wished, given that the romance is so central and often so problematic,” notes O’Hara. “A lot of men sneered at it in a way they (mostly) were less able to do when faced with the success of Wonder Woman, a little further on, or Ocean’s 8 (now the most financially successful of the Ocean’s franchise).

“But my standard response to sneering men is to point out [Twilight] is almost exactly as good as the first few Transformers (great start, lesser sequels, silly premise and dialogue) and challenge them on why one is acceptable and the other not, without using sexism. That usually shuts them up.”

—

Maria Lewis is a journalist, screenwriter and author of It Came From The Deep and the Who’s Afraid? novel series, available worldwide.