These Are The Men Who’ve Died In Mandatory Detention Since The Last Election

On Friday, 23-year-old Omid Masoumali died after setting himself on fire. He is not the only one.

On Friday afternoon, the Department of Immigration and Border Protection announced that Omid Masoumali, the 23-year-old Iranian man who set himself on fire in Nauru last Wednesday, has died of his injuries in Brisbane Hospital.

“This is how tired we are, this action will prove how exhausted we are. I cannot take it anymore,” a witness reported Omid as saying shortly before he set himself alight during a visit by UN officials, who witnessed his actions. Omid was airlifted to Australia almost a day later after receiving initial treatment at the Republic of Nauru hospital. Omid’s wife Nana, who has criticised the Australian government for not moving more quickly to provide him with emergency care, was with him when he died. She will likely be transported back to Nauru in the near future.

Heartbreaking message from one of Omid’s friends on Nauru. #CloseTheCamps #BringThemHere pic.twitter.com/ib6v95WQLK

— Mums4Refugees (@Mums4Refugees) April 28, 2016

Omid, who had been recognised as a genuine refugee by Australian immigration, had been in detention on Nauru for three years. According to the Refugee Action Coalition, four asylum seekers on Nauru attempted suicide on the same day as Omid by drinking washing powder. Another two Iranian women have been missing from Nauru since Sunday, with authorities believing they may have attempted to escape the island by stealing a boat.

As these stories dominate headlines, the future of Australia’s offshore detention policy looks ever more doubtful. On Wednesday, the Papua New Guinean government ordered the closure of Australia’s Manus Island detention centre after the PNG Supreme Court ruled the detention of asylum seekers and refugees was illegal. On Saturday, Broadspectrum, the company that runs Australia’s detention centres on Manus and Nauru, was bought out by Spanish consortium Ferrovial, who immediately released a statement saying “this activity will not form part of its services offering in the future”.

With a likely election only two months away, and asylum seekers looking to be a crucial election issue yet again, it’s worth remembering the human toll Australia’s mandatory detention regime has taken over the last few years. According to Monash University’s Australian Border Deaths Database, at least 14 men in the workings of Australia’s detention regime have died, 10 from suicide. Eight of them died in onshore or offshore detention centres.

–

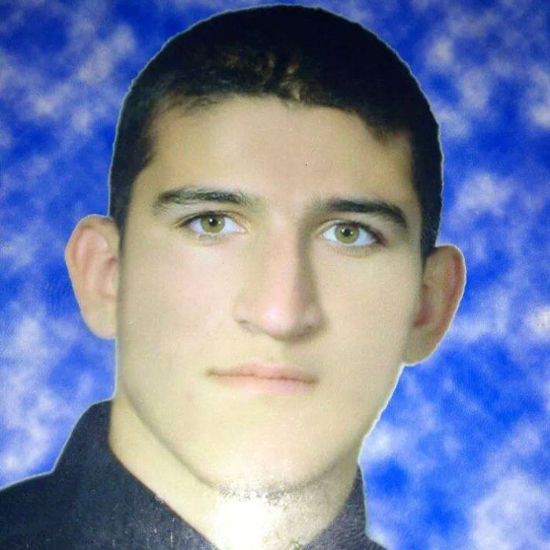

Reza Barati

Another 23-year-old Iranian man, Reza Barati was murdered during an attack on the Manus Island detention centre by locals, riot police and private security staff in 2014. It took more than six months for two men to be charged with Reza’s murder; a court later heard that his head was beaten repeatedly with a length of wood before having a large rock dropped on it.

While the two men — both of whom were employees of G4S, the private security company contracted to provide guards for the centre — were found guilty of murder and sentenced to at least five years’ jail earlier this month, the trial’s main witness contends that he was threatened and tortured throughout the trial by the defendants and other G4S guards. Other Manus detainees maintain more people were involved in Barati’s death.

–

Hamid Khazaei

A 24-year-old from Iran, Hamid died in Brisbane’s Mater Hospital in September 2014. An asylum seeker held on Manus Island for nearly a year, Hamid became sick after a cut on his foot became infected with a rare bacteria. A report into his death found that a recommendation to move Hamid to Australia for urgent treatment wasn’t acted on for more than 24 hours, during which time his condition considerably worsened.

A Four Corners expose earlier this week, ‘Bad Blood’, heard from doctors involved in Hamid’s case who believe his death “could have been prevented”. Australian Medical Association president Dr Brian Owler described the delays in Hamid’s treatment, including a public servant neglecting to check their emails once they had gone home for the day until the following morning, as “pathetic”, and told Four Corners that if Hamid had been transferred to a Port Moresby hospital in time, “he would still be alive today”.

–

Fazel Chegeni Nejad

Fazel Chegeni was found dead in bushland two days after escaping from Christmas Island detention centre in November 2015. An Iranian Kurd, Chegeni was tortured, starved and raped by the Iranian regime before fleeing in 2011. He arrived on Christmas Island later that year and was found to be a genuine refugee by Australian authorities in 2013.

Throughout his detention, Immigration officials, case managers and psychologists stated that Chegeni’s history of trauma was being severely exacerbated by the detention process, and warned against continued incarceration. Chegeni attempted suicide multiple times in the weeks before he escaped from the Christmas Island centre. He had been in and out of detention for more than four years.

–

Mohammad Nasim Najafi

A 27-year-old from Afghanistan, Nasim died in WA’s Yongah Hill Immigration Detention Centre in July 2015 of a suspected heart attack. An epileptic, Nasim frequently struggled to receive medical attention at Yongah Hill, with detainees claiming serious conditions were routinely treated with “Panadol and sleeping pills“.

Several weeks before he died, Nasim’s room was broken into by several men who beat him and trashed his belongings. Shortly after, Nasim was relocated to a two-by-two-metre solitary cell with no bathroom. Earlier that year, news outlets had reported that the WA state government was housing hundreds of convicted criminals at Yongah Hill, a centre designed to house non-dangerous asylum seekers.

Detainees and guards have complained to media that Yongah Hill was inadequately prepared to handle high-risk offenders of the kind the centre began taking on in 2014, with “child molesters who have been in prison for 10 years” being housed in the same facilities as “young men who are 18 years old”. The resulting hostility and tension between inmates and untrained guards left many asylum seekers scared to leave their rooms.

–

Khodayar Amini

In October 2015, 30-year-old Hazara Afghan man Khodayar Amini doused himself in petrol and set himself on fire during a video call with a pair of refugee advocates. Authorities later found his burnt body in parkland in Dandenong, on Melbourne’s outskirts.

Khodayar arrived in Australia by boat in 2012 and was released into the community on a bridging visa five months later. On multiple occasions throughout his time in Australia, Khodayar claimed that he was beaten, harassed and intimidated by police and immigration officials, and frequently expressed fear that his unstable situation would see him deported by authorities back to Afghanistan. He was sent back into detention for almost a year over a minor argument with a government department office, an incident in which a court later found him innocent of misconduct.

In the months leading up to his own death, the news of Najafi dying at Yongah Hill reached him. Khodayar frequently described Najafi as his “best friend”. Amini was living in western Sydney at the time, but a phone call from a friend informed him that the Australian Border Force had raided his old address, looking for him. Amini fled the state, eventually pulling up in the bushland outside Dandenong, where he slept in his car.

In a letter to another refugee advocate, written the day before he died, Khodayar said the following:

“I, Khodayar Amini, write the following few sentences with my blood for those apathetic so called human beings…Yes they did this to me, with slogans of humanity, sentenced me to death. My crime was that I was a refugee. They tortured me for 37 months and during all these times they treated me in the most cruel and inhumane way. They violated my basic human right and took away my human dignity with their false and so called humane slogans.”

–

Ali Jaffari

In September 2015, 40-year-old Ali Jaffari died in Yongah Hill as well. Yongah Hill detainees and guards found Jaffari in his room toilet, where he had wrapped himself in a sheet, doused himself in accelerant and set himself on fire, resulting in severe burns to 90 percent of his body. He died a day later. Refugee advocates claim Jaffari had attempted suicide multiple times.

An Afghan Hazara, Jaffari came to Australia by boat in 2010 and was granted refugee status. Unlike Nasim, Jaffari was detained in Yongah Hill as an inmate after failing the ‘character test’ required for migrants to keep their visa. In 2014 Jaffari was convicted of one count of accessing child pornography material using a carriage service, after using his laptop to look up sexual images of teenage boys and girls in a St Kilda public library. In 2013, meanwhile, Jaffari was found guilty of indecently assaulting a boy and attempting to indecently assault another, and was placed on the sexual offenders register for 15 years. Further charges against him, of child stealing, attempted child stealing and unlawful assault, were thrown out of a Geelong court in 2014.

–

Robert Peihopa

New Zealand man Robert Peihopa, 42, died in Sydney’s Villawood detention centre in April 2016, where he had been held for around 10 months. While authorities gave the official cause of death as a heart attack, Robert’s friends and fellow detainees believe he may have had an altercation with another party before he died. Ra Fowell, another Kiwi inmate at Villawood and longtime friend of Peihopa’s, claimed Robert had “two black eyes and a cut on the face” when his body was found. Vaelua Lagaaia concurred, saying “it was unbelievable” to think Peihopa suffered a heart attack as he exercised rigorously.

Earlier in the year, the long-term detainment of New Zealand citizens after being stripped of their Australian visas was raised by NZ Prime Minister John key with his Australian counterpart Malcolm Turnbull; a recent Australian Senate committee heard that 183 New Zealand citizens are in onshore detention.

–

Leorsin Seemanpillai

Leorsin ‘Leo’ Seemanpillai killed himself in May 2014 by setting himself alight outside a petrol station in Geelong. A Tamil from Sri Lanka, Leorsin arrived in Australia in January 2013 after living in a refugee camp in India, and was awaiting the Immigration Department’s word on whether he would be issued a protection visa.

“He feared for his life if he was returned to Sri Lanka,” Tamil Refugee Council spokesman Aran Mylvaganam said at the time. “His housemates have told me he repeatedly talked about being sent back, he was quite worried about it.”

Another member of the Tamil Refugee Council, Trevor Grant, related how Seemanpillai had expressed wishes to become an organ donor. Several of his organs were removed for donation after he died.

More than a year after his death, funeral and burial, Leorsin’s parents and brother were still being denied visas to visit his grave by the Department of Immigration.

–

‘Reza’

In late October 2015, 26-year-old Iranian man Reza hanged himself with a bag strap from a railing in Brisbane Airport. He had been living in Australia on a bridging visa since 2013 after fleeing Iran and spending several months in various detention centres. His last name was not published by most media outlets due to fears of reprisals against his family.

Speaking to BuzzFeed’s Rob Stott, some of Reza’s friends recounted how the constant fear of being detained and deported back to Iran had a devastating effect on his mental health: “At the end he got worse and worse. On a number of occasions he tried to harm himself and he had scars all over his body, and none of the authorities cared.”

Reza had been living in Melbourne for two years, but “thought that he must escape from this area as police and people were chasing him. He got to Brisbane and he stayed in the street until morning,” according to a friend. The same friend told the Guardian that the morning before he died, Reza told him by phone: “I am tired. Always police and people follow me. I want to kill myself. Tell my family.”

–

Rezene Mebrahtu Engeda

A 35-year-old man from Eritrea, Rezene drowned himself in the Maribyrnong River in February 2014. He entered Australia via Nairobi, Kenya in 2009 on a spouse visa, after fleeing Eritrea along with a staggering proportion of that war-torn country’s young men.

After his spousal relationship deteriorated, however, Rezene applied for refugee status with the Department of Immigration on the grounds that he would be killed by the government if he was returned home. Countless reports from agencies like UNHCR, Human Rights Watch and the Red Cross detail how returned refugees are routinely imprisoned, tortured, disappeared and killed by the Eritrean government, which regards any citizen who refuses to serve in the army until the age of 50 as a deserter.

Three years later, having been unable to work or receive benefits due to his visa restrictions, Rezene was told by Immigration to attend a meeting the following week, where Rezene strongly suspected he would be told to return to Eritrea. Writing for Overland, Melbourne journalist Thomas Kent tells of how Rezene asked a friend out for a beer that weekend, an invitation his friend was too busy to accept. The day he was due to attend his Immigration meeting, Rezene went missing. His body was pulled from the Maribyrnong later that week.

–

Omid Ali Avaz

Omid Ali Avaz was 29 years old when his body was found in Brisbane’s Dutton Park in March 2015. He had been in Australia since 2011 after fleeing his native Iran and attempted suicide numerous times as he was moved in and out of detention over the next four years. Omid was one of the first refugees to be issued a controversial 449 or ‘safe haven’ visa by the Coalition government.

449 visas give refugees temporary safe haven for a length of time decided by the Immigration Minister and have their right to stay in the country reassessed when that time expires. Temporary protection visas for refugees and asylum seekers have long been a source of contention. In 2006, a Senate committee concluded that TPVs resulted in a “considerable cost in terms of human suffering”, as their recipients were constantly unsure and afraid that they would be sent back to the countries from which they’d fled.

The month before he died, Omid was granted a 12-month 449 visa. Shortly after, his mental health deteriorated on learning of the death of his mother back in Iran. 449 visas do not provide recipients with the right to family reunion.

–

Two men — ‘Raza’, a 27-year-old Afghan Hazara who threw himself under a train in June 2015, and an unnamed 27-year-old Indian student who hanged himself in his cell at Maribyrnong detention centre in February 2014 — have not been included in this list due to insufficient information.