We’re Still Coming To Terms With Prince’s Massive Impact On Music And Culture

Prince changed the way millions of people think about a colour for a start.

How enormous is the legacy of Prince Rogers Nelson? Before we even address his impact on music over the past 40 years, let’s start with the colour purple. Start with the fact that Prince colonised an entire secondary colour. He took something basic to our cultural psychology – historically associated with royalty and with the church – and made it his own, his personal brand.

We used to take it for granted; in some ways it was a running joke to refer to him as the Purple One or His Purple Highness. Sometimes Prince eschewed the association (think of the sky-blue suit he wears in the 1985 video for ‘Raspberry Beret’, his immediate follow-up to the Purple Rain phenomenon), other times he took part in the joke with a nodding wink.

Melbourne’s Arts Centre Will Be Lit Purple Tonight In Honour Of Prince

But when Prince died, the cheeky branding, the running joke, was transformed into a powerful symbol of grief and adoration. Worn by fans in mourning, splashed all over social media, lighting up the Empire State Building and the Eiffel Tower – it seemed the entire world was awash with purple in tribute. Prince changed the way millions of people think about a colour.

That is astounding, and kind of weird, when you consider it. Has any other musician or artist accomplished such a feat on the same scale? Johnny Cash was the Man in Black – but you don’t look at the colour black and think of Cash. Not even close. But with purple, many or most of us do think of Prince. And that colour is 100 per cent Prince: audacious and overflowing with creative genius, but playful too.

We’re Still Processing This Loss

It’s been one year as I type this since news reverberated around the world like a thunderclap that Prince had tragically collapsed at Paisley Park, his mansion and recording complex in Chanhassen, Minnesota, aged 57. It seems impossible it’s been a year; it feels like just the other day, and I think that’s because the pain is still quite raw. We’re still processing this loss. And we’re still unravelling how much Prince meant to us and to our culture.

A short time after the news hit, and after we all scrambled to make sure it wasn’t a terrible mistake or a sick prank, a friend – a music critic from New York – posted on Facebook asking if his friends were OK. And that didn’t seem like a self-indulgent or unreasonable thing to ask. My answer, like many others on the thread, was “No, I’m not OK.” Only having my one-year-old son to look after kept me together that day.

So much of this kind of grieving is sharing personal stories. I won’t delve too much into mine, except to say that I first saw the video for ‘1999’ on MTV at the age of 11. It blew my preadolescent mind, and Prince was an influence on me and was there for me at every stage of my life for the next 34 years. He was the point from which all of my interest in alternative and dance music unspooled. I wouldn’t be a DJ if not for Prince, nor would I be someone who cared enough about music to write about it.

A Benevolent Recluse

More astute writers than me have explored the ways our culture publicly grieves celebrities on social media – the tropes we follow and the rituals we observe. But it’s worth touching on here, not only because his death was so overwhelming, but because his odd and sometimes contentious relationship with the media and the music industry made it a special case. Prince and his estate have famously resisted the online and digital age.

At the time he passed, his music wasn’t available on Spotify (it finally is now, as of February of this year); most of his back catalogue has never been remastered for modern digital audio systems; and his epochal videos aren’t easily found on YouTube. Is this an arrogant and shortsighted policy that will effectively prevent a new generation from accessing and being influenced by his work? Or in typical Prince fashion, does it actually enhance his mystique, obliging us to seek out and pay for his work, and thus value it more?

[He] used his power and his millions to help as many people as possible.

In the immediate aftermath of his passing, when we were all still in shock and looking for ways to share it and talk about it, the latter seemed true. Without being able to simply pop the video for ‘When Doves Cry’ onto our timeline, we had to be creative. We had to share Sinead O’Connor’s tearful video for ‘Nothing Compares 2 U’, which Prince wrote and which perfectly summed up our shock and misery. Or we had to go more abstract, with portraits of the man or his album covers that communicated the force of the music we all had in our heads.

Bootleg clips of Prince’s appearances in other media were also widely shared in lieu of his videos. Seeing him as consummate entertainer performing ‘Starfish and Coffee’ on Muppets Tonight, or unleashing an incredible off-the-cuff version of ‘Summertime’ at a soundcheck in Japan, were crushing reminders of what we’d lost. Then there’s the live version of ‘It’s Gonna Be a Beautiful Night’ from the Sign o’ the Times concert film that went viral when posted by AFROPUNK, with the pithy and perfect caption: “Simply unforgettable/This man was a genius”. It was poignant evidence not only of Prince’s incredible powers as a performer, but of his far-reaching influence on underground culture – particularly black underground culture, from boogie to Detroit techno to punk-funk.

Beyond The Music

Then we suddenly started hearing stories about his tremendous generosity and his philanthropy programs, which he kept secret from the public due to his strict faith as a Jehovah’s Witness. He donated extensively to inner-city education, environmental and anti-poverty initiatives. “There are people who have solar panels on their houses right now in Oakland, California [and] they don’t know Prince paid for them,” commentator Van Jones, who assisted Prince with some of these programs, told CNN.

He paid for funk innovator Clyde ‘Funky Drummer’ Stubblefield’s medical bills, helped Lauryn Hill and her kids when she got into legal trouble and sent money to the family of Trayvon Martin, the Florida teenager whose brutal shooting death in 2012 sparked the Black Lives Matter movement. The portrait that emerged was of a reclusive but benevolent titan who used his power and his millions to help as many people as possible in what was ultimately a short life.

While Prince was never openly involved in politics, he’d always had a political edge. ‘Partyup’, the last track on 1980’s Dirty Mind, ends with an anti-war chant: “You’re gonna have to fight your own damn war/’Cause we don’t wanna fight no more.” The cover art for his 1981 album Controversy addresses gun control. Several of his hits, including ‘1999’ and ‘Sign o’ the Times’, lament the nuclear arms race. In the ’80s his raunchy lyrics became highly controversial in the mainstream when they were singled out by a powerful political lobby (spearheaded by then-Senator Al Gore’s wife Tipper). That ultimately led to the recording industry’s iconic ‘Parental Advisory’ warnings that were, of course, disproportionately imposed on black artists in the hip-hop era.

In the ’90s, Prince’s fierce clashes with Warner Brothers, his record label, were historic in the struggle for musicians to control their own work, and Prince made it overtly about race when around that time he appeared in public with the word SLAVE written on his cheek. In his presentation of an award at the 2015 Grammys, he came right out and said that Black Lives Matter. And it occurred to us that Prince had, in his own unique way, always been there in the fight for that cause.

We even began attributing supernatural powers to him. Take his apocalyptic Super Bowl halftime show in 2007, which he performed in the pouring rain. It lent incredible atmosphere, not to mention real danger, to the proceedings, in front of a TV audience of hundreds of millions around the world. ‘Purple Rain’ in the rain? – c’mon.

Watching footage of it after his death, we nervously joked that Prince must have had command of the weather that night – but deep down we might have actually believed it. In this Billboard commentary marking the tragic anniversary, author Joe Lynch says that we still can’t process Prince’s death because he always seemed to be more like a god than a mortal man – and it doesn’t seem fanciful or OTT, it just seems spot-on. That’s the effect Prince has on us.

Prince Could Do It All

This monumental aspect to Prince – so ironic in someone who was so physically short in stature – has made it difficult to quantify his importance to contemporary music. He was so singular, not only in his masterful talent but in the effortless way he combined genres from rock to funk to R&B and jazz, that he was a genre unto himself. It seems he influenced everyone without having direct antecedents the way, say, the Beatles or Nirvana did. You can hear it in techno and house and in the disco edits of Late Nite Tuff Guy. You can hear it in the music of white indie bands like Phoenix and Of Montreal and Hot Chip. You hear it in odd places – INXS and Sufjan Stevens and Flight of the Conchords.

Most of all, of course, you can hear it in the unconventional and Afro-futurist and often sexually ambiguous black music of today. Because Prince never fully embraced hip-hop, a generation of black popular music seemed to sidestep his legacy, and at one point it might have been easy to conclude his time was past. But in the 2000s a new wave of black artists began fusing R&B and soul with pop and rock and electronica, combined with a playful adventurousness that defied the often rigid norms of ’90s hip-hop. Andre 3000’s The Love Below was a supremely Prince-like watershed moment, as was Janelle Monáe’s The Audition. Kanye and Pharrell got in on it too. Now, in the days of Frank Ocean, FKA Twigs and Kelela, it’s apparent once again that we’re living in a world created by Prince.

He inspired a generation of fans to loosen up and be themselves no matter what the world might think.

But there’s never been someone to take his place, or be “the next Prince.” Can you even imagine what such an artist would be in this day and age? Prince was one of the greatest songwriters of his generation, and also one of the greatest singers, dancers, bandleaders, record producers and multi-instrumentalists. His guitar playing alone would have made him an all-time great. He was regularly described as the greatest guitarist since Jimi Hendrix.

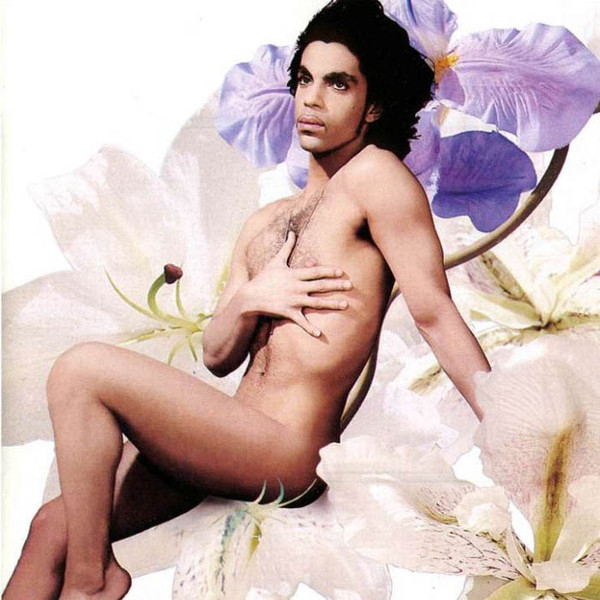

All that before you try to unravel out how important he was as a sex symbol who not so much challenged conventions of race and gender and sexuality but turned them on their head. He teased them, took them apart. Importantly, he also made women’s emotional and sexual needs prominent in his work on songs like ‘If I Was Your Girlfriend’. With his outrageous style and constant pushing of boundaries – from singing about oral sex to his pink and purple phallic guitars to appearing naked on an album cover – he continually trounced our expectations of what men, and especially black men, were supposed to be in the public eye.

Imagine how controversial this would’ve been in 1988!

Like David Bowie, he inspired a generation of fans to loosen up and be themselves no matter what the world might think. His supreme control over his image, his utter confidence and grace in toying with it and always reinventing it, the fun he had with it, were as much a part of his genius as his music. It was apparent in his hijacking of the colour purple, but also in his use of symbols in text that long predated mobile phones and emojis (song titles like ‘I Would Die 4 U). This culminated in his famous invention of a nonverbal symbol to take the place of his name, obliging the entire music industry to scramble to accommodate him in printed materials.

Unfortunately it took his terribly sad death for many of us to take time to ponder all that Prince was. It’s as though he was so big that we took him for granted; like a mountain that we got used to living next to and didn’t always look up at.

–

Jim Poe is a writer, DJ, and editor based in Sydney. He regularly contributes to inthemix, SBS, Red Bull Music and The Guardian and co-hosts The DHA Weekly on Bondi Beach Radio. He tweets from @fivegrand1.