Time To Ban Men? We Talked To Australian Music Venues Taking A Stand Against Sexual Assault

"Women-only events aren't really a good long-term solution for creating cultural change."

This post discusses sexual assault.

–

Last week, it was announced that Sweden’s largest music festival, Bråvalla, will not be going ahead next year due to a high number of sexual assaults at this year’s event. Over the four days of the festival, police received four reports of rape, and 23 reports of sexual assault.

In response to the announcement, Swedish comedian Emma Knyckare suggested a new festival be held, where “only non-men are welcome until ALL men have learned how to behave”. Her tweet quickly gathered steam, and a few days later tentative plans for the festival were underway.

It’s too early to tell whether it will actually come to fruition, but the speed of the response speaks volumes about people’s frustration and sadness with gendered violence at festivals.

This is not the first time a man-free festival has been suggested as a solution to endemic sexism in the music industry, and past attempts have quickly become mired in troubles of their own. The Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival famously tore itself apart in 2015 over its exclusion of transgender women.

The path to safer music spaces can seem so fraught that shutting down altogether, as Bråvalla has, can seem like the only option. There are other options, however, and some of them are slowly starting to yield results here in Australia.

We spoke to some of the Australian venues and festivals trying to create safer music spaces about what’s working, what isn’t, and whether banning men is the way forward.

Paving The Way: Melbourne’s Safer Music Spaces

Melbourne’s Cool Room is not your typical clubbing experience. For one, posters at the door detailing what you can and cannot do include stern directives against homophobia, sexism, and unwanted touching. You’re also guaranteed to collect at least one phone number — a text hotline connecting you directly with the club’s numerous Safety and Inclusivity Coordinators, who roam around in clearly marked t-shirts making sure club-goers feel safe.

“We tell people to leave systems of oppression in the bin when you go in.”

Kate Pern is one of these coordinators, and describes Cool Room as part of a long-term attempt to “really change the culture of what’s normal and accepted in clubs and music venues”. While her job sometimes entails getting people kicked out, she says more time is spent pulling people aside for “chats” aimed at getting them to see the need to change their behaviour.

These chats are, according to Kate, surprisingly effective. “This one guy I had a chat to, it was clear he was just having a sick one and wasn’t thinking about what he was doing. When I let him know a couple of people had told me he was making them uncomfortable, he was like ‘oh my god, I’m so sorry, I’ll kick myself out! I don’t want to be one of those guys!’”

Photo: Cool Room.

There are, of course, instances where violence is severe, and perpetrators are removed from the venue. Staff at Cool Room are trained to approach complaints by first and foremost believing victims and responding to their needs, including giving them a choice about how the perpetrator is dealt with.

“Our first priority is keeping people safe, obviously, but as long as everyone’s safe we’d rather not just kick someone out”, Kate says. “We’d rather actually have them learn something and not do it again.”

Dial-Up is another regular Melbourne music event with a particular focus on changing the culture of music spaces. Like Cool Room, Dial-Up has roaming safety coordinators and a list of expectations posted outside the space.

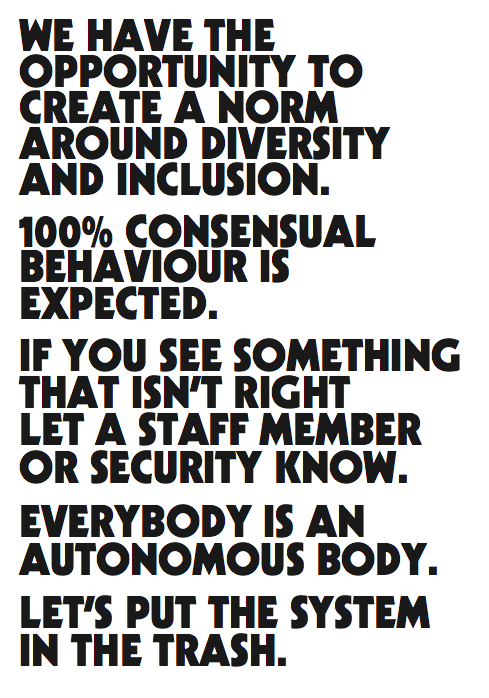

The code of conduct posted outside Dial-Up events

DJ and coordinator James (Jimi) Cleverley says they’re just doing what they consider “the minimum in terms of safety and creating a safe space — what we think every space should be expected to do. We tell people to leave systems of oppression in the bin when you go in.”

As for whether the system works, Kate and Jimi both say the impact is resounding.

“We have a lot of people on the night who say they just feel so comfortable,” Kate says. “Even things like women feeling comfortable to take their tops off, people feeling comfortable to express their gender identity. Even just being able to close your eyes when you’re dancing is something that I certainly don’t feel safe doing in a lot of other venues in Melbourne, but I love to do it here.”

It’s a big contrast, she says, to the way things are everywhere else. “I get quite shocked, when I go to a venue I don’t normally go to, about how much of the night I spend fending off dudes and telling them to leave my friends alone.”

Safety At Scale: Can This Approach Work At Festivals?

Cool Room and Dial-Up, of course, are small nightclubs — a far cry from the enormous crowds at festivals. But Kate is optimistic about the possibility of applying Cool Room’s approach on a bigger scale.

Cool Room staff training, for example, “is actually pretty basic stuff — you can teach these things in a pretty short period of time”. Part of the problem, as Kate sees it, is that security staff do not always receive training that centres on listening to victims and educating offenders before situations escalate to sexual assault, and that this can make it harder for people to report concerns.

Jimi also emphasises the importance of creating a culture of self-regulation within club and festival spaces. “When I’m at Dial-Up, I don’t get a sense of big bro-ey culture, or of that being accepted,” he says. “Even if some bros did come, and wanted to sort of bro out, I feel like the majority of people on the dancefloor just wouldn’t accept that behaviour.”

This deliberate attempt to shift festival culture is starting to appear in the Australian festival scene too. Organisers of Secret Garden told Junkee that creating a culture where everyone is welcome and safe is essential. In a similar vein, following a spate of sexual assaults at Rainbow Serpent festival in previous years, the 2017 festival featured the inaugural “Nest”, a safe space featuring a respite and support services for victims of sexual harassment.

Photo: Rainbow Serpent.

Rainbow Serpent Social Services Manager Mel Pearson told Junkee that The Nest was incredibly well received. “The range of support people required was one of our biggest surprises,” she said. “[There were a number of] young women overwhelmed from coming to a festival on their own for the first time.”

Of course, the space was not a silver bullet, and the 2017 Rainbow Serpent festival was not free of sexual assault, but organisers say The Nest was nonetheless “a huge success in its first year” and intend to continue improving it for future festivals.

“Women-only events aren’t really a good long-term solution for creating cultural change.”

In addition, The Nest actively welcomed trans and gender diverse festival-goers, in doing so countering one of the pitfalls often associated with “women’s only” festivals and safe spaces. Supporting the queer community was also a focus at Cool Room and Dial-Up. It’s part of the reason organisers of these spaces tend towards a strategy of educating and attempting to shift culture rather than enact outright bans on men.

“Education and affirmative action strategies designed to shift [advocate] consent culture will have a broader impact on gender-based violence than banning all cis men from festivals,” Mel says of Rainbow Serpent’s approach.

“It’s imperative to include trans and gender diverse people when formulating any policy relating to gender-based violence. Research shows trans and gender diverse people are a high risk group to experience sexual assault, so to exclude them is to ignore the evidence.”

Kate Pern agrees. “The philosophy of Cool Room is that we don’t want to exclude anyone. Our night isn’t a queer night, but it’s a very queer-focused night, so the priority for us is to have queer and trans people being safe and feeling comfortable, and women and ethnic minorities as well. There’s definitely a place for women-only events, but I don’t think that’s really a good long-term solution for creating cultural change.”

The way forward, Kate says, has to be towards creating that cultural shift. Regarding Bråvalla’s closure, she says “cancelling an event is not going to help change culture, which is what needs to happen”.

“It’s good that they’re outraged about it, though. We need more outrage about this.”

–

If you or someone you know is impacted by sexual assault call 1800RESPECT on 1800 737 732 or visit 1800RESPECT.org.au. In an emergency, call 000.

Men can access anonymous confidential telephone counselling to help to stop using violent and controlling behaviour through the Men’s Referral Service on 1300 766 491.

–

Feature image: Hideout Festival/Facebook.

–

Sam Langford is Junkee’s Staff Writer. She tweets at @_slangers.