Review: Dev Patel Vs. Google; Who Was The Real Hero Of ‘Lion’?

How might a story like this -- which involves a lot of time spent staring at a computer -- unfold onscreen?

Saroo Brierley’s extraordinary life made worldwide headlines five years ago. Lost on a train as a five-year-old child in rural India, then adopted by a family in Tasmania, as an adult Brierley used Google Earth to track down his hometown and his birth family. It’s a story of courage and determination as big as India itself.

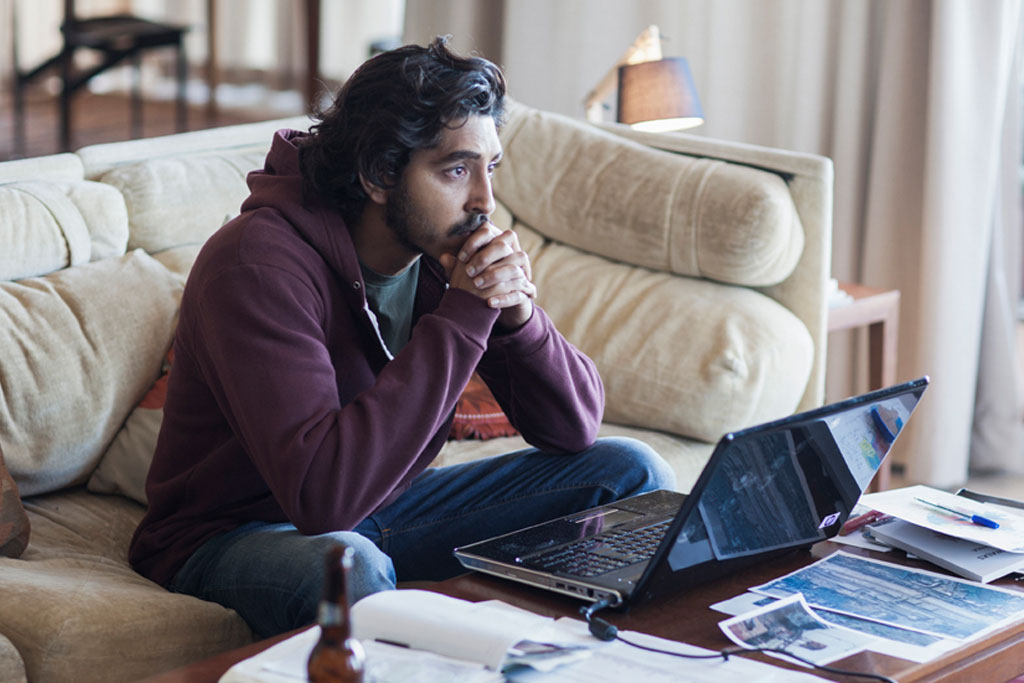

It makes a great memoir, and certainly a great ad for Google… but the challenge for director Garth Davis (making his feature debut here after well-received work on Top of the Lake) is to make staring at a computer screen for months on end look exciting. It’s also a challenge for Dev Patel, a gangly, physically exuberant onscreen presence who here must access something more stolid and brooding. Both succeed… but only partly.

Let’s Start At The Very Beginning

How might a story like this unfold onscreen? The film’s marketing focuses on the emotional journey of adult Saroo (Patel); and in your average biopic, we’d begin with a shocking moment that jolts him back into a long-repressed past. The story would unfold in flashback, gradually acquiring more detail as Saroo delved further into his memories, aided by his loyal girlfriend Lucy (Rooney Mara) and his kindly adoptive parents Sue and John (Nicole Kidman and David Wenham).

Thankfully, Lion chooses to begin where its story is strongest – in India, with the under-promoted but excellent Indian cast. We meet young Saroo (Sunny Pawar) daydreaming in a cloud of butterflies. It’s a lovely metaphor for the way we can sometimes feel memories clustering around us, evanescent and gorgeous.

Brierley’s memoir, A Long Way Home, makes clear that his remembering wasn’t like exploring a dusty attic; he preserved his earliest memories through a long, concentrated, reiterative process. As a child he had often lain in bed, intently visualising the landscape around the town he called ‘Ginestalay’. He kept a map of India on his bedroom wall. At age six, he had sat down with Sue and sketched his house, the town and local landmarks, and Brierley remembered more by telling what he knew to fellow adoptees, friends and trusted teachers.

Davis and cinematographer Greig Fraser present the film’s early scenes the way a little child remembers: a golden world full of adventure, where your big brother Guddu (Abhishek Bharate) is your hero and your mum (Priyanka Bose) is the most beautiful woman in the world. It’s easy to understand why Saroo insists on coming with Guddu to the train station to scrounge coins from the carriage floors.

Pawar is Lion’s true star. He carries the first half of the film with tremendous natural charm as Saroo wakes up alone, trapped in a decommissioned train that takes him all the way to Calcutta. We see the bustling Bengali-speaking city as it looks to a small Hindi-speaking child: a mass of anonymous, jostling bodies by day; an uncanny hush at night. I liked these quieter scenes. Saroo falls in with local street urchins, wordlessly accepting a sheet of cardboard to sleep on, and picks his way between sleeping monks to steal fruit offered at a candlelit shrine.

Through Pawar’s watchful stillness and the ellipses of Saroo’s childish perspective, his poverty and the dangers he faces are implied but never dwelled upon. Glamorous Noor (Tannishtha Chatterjee) and her friend Rawa (Nawazuddin Siddiqui) take a not entirely altruistic interest in Saroo; and at the Calcutta orphanage where he ends up, Saroo watches another traumatised boy (Surojit Das) become the focus of more unwelcome adult attention. It’s these scenes we remember when we meet Saroo’s adoptive brother in Tasmania, Mantosh (played as a child by Keshav Jadhav, and as an adult by Divian Ladwa).

The adult Saroo emerges, wetsuit-clad, from the chilly Tasmanian waters as if baptised. He is reborn as a buff, tousle-haired babe… with an Australian accent so effortless you really do feel he was raised here. The fairytale qualities of the film’s first half reflect that it’s all memory: a reflection on how disorientingly serendipitous his life has been.

Floating High Above The World

It’s easy to forget how our ideas about the world are shaped by the ways we represent it. The Mercator map projection, first drawn up in 1569, has become the default two-dimensional image, embedding its distortions into our understanding of the shapes and distances of oceans and continents. Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion map (1943) more radically refuses conventional understandings of orientation and direction; it can be regarded from any angle. And the famous Blue Marble photograph (1972), taken by the Apollo 17 crew, introduces an idea of wholeness: a perspective that forecast today’s era of remote satellite imagery.

This Google Earth tutorial from 2007 shows how Saroo could spin and scroll over a floating marble, looking down upon the world with the clarity of a god. And Lion adopts free-floating, bird’s eye perspectives that mirror this interface. Fraser’s camera swoops over Tasmanian coastlines and Indian landscapes in crane and helicopter shots that follow human journeys on foot, in trains and cars.

There’s something exhilarating, terrifying, sublime, about looking down on a landscape – which artists from Caspar David Friedrich to Fred Williams have sought to capture. It’s the urge to know the world differently, to seize new perspectives, which leads people still to climb mountains like Everest and Kilimanjaro… and even to clamber sacrilegiously over Uluru.

In a key scene, Saroo and Lucy climb Kunanyi (Mt Wellington), and Saroo gazes pensively out over Hobart. But Lion can’t quite find a representational language for the friction between the capabilities of technology and the subjective world of experience. The film becomes flat and slow as Saroo submerges himself in an unsatisfying digital prosthetic for his still-vivid memories. He sulks in darkened rooms like a conspiracy theorist, slumping on a bare mattress, staring at a laptop or annotating a giant wall map, while those around him try limply to be supportive.

There really isn’t very much for Mara, Kidman and Wenham to do – although Kidman manages to sell a strange monologue in which Sue explains the weird white-saviour ‘vision’ that compelled her to adopt brown kids rather than have her own.

In focusing on the technology Saroo uses, the film misses a key opportunity to think about cultural and psychological mapping. Missing from the middle and end of Saroo’s journey home are the other places where he fits and doesn’t fit. I was intrigued by his fraught relationship with Mantosh, and the Indian friends he meets in Melbourne while studying hotel management are frustratingly under-used here. When Saroo says his mum worked as a construction labourer, shock and pity cross their faces. I wish Davis had made more of such moments.

Because Saroo’s story ends in a miraculous family reunion, the technology becomes the hero – but what really got Brierley home was his capacity to hold onto his memories and to go on inhabiting them. Lion is a feel-good story that works best when it uses the visual language of cinema to map such inner worlds onto outer ones.

—

Lion is in cinemas now.

–

Mel Campbell is a freelance journalist and cultural critic. She blogs on style, history and culture at Footpath Zeitgeist and tweets at @incrediblemelk.