Real-Life Dinosaurs Are Much More Radical Than Anything In ‘Jurassic World’

Why use "gene-splicing" to reinvent dinosaurs, when they're being reinvented by science all the time?

Twenty-two years after Steven Spielberg first tapped amber and life, uh, found a way, Jurassic World stomps into cinemas this week.

And it reveals a lot about the hyperbole governing modern blockbuster cinema that the film’s dino-villain does not appear in the fossil record, but rather is an invented super-predator: a genetic hybrid of Gigantosaurus, Rugops, Majungasaurus and Carnotaurus that theme park scientists led by Dr Henry Wu (BD Wong) have dubbed Indominus rex.

Jurassic World, now owned by the Masrani Corporation, is well and truly open to the public; and as operations manager Claire Dearing (Bryce Dallas Howard) says, “Every time we’ve unveiled a new attraction, attendance has spiked. Corporate felt genetic modification would up the wow factor.”

“They’re dinosaurs,” retorts the park’s Velociraptor keeper, Owen Grady (Chris Pratt). “Wow enough.”

Velociraptor has always been one of the Jurassic Park franchise’s signature predators. Yet compared to the mighty Indominus, the raptors are comparatively low-key. Owen seems to have a working relationship with his charges closer to that of a circus trainer than the safari gamekeeper role of Robert Muldoon (Bob Peck) in the first film. And will Owen’s pack actually end up helping the humans battle Indominus?

“If we do this,” says Owen, “we do this my way.”

You Don’t Need Gene-Splicing To Radically Reimagine Dinosaurs; They’re Reimagining Themselves

“We have learned more in the past decade from genetics than a century of digging up bones,” boasts Claire in Jurassic World. But despite the involvement of celebrity palaeontologist Jack Horner as technical consultant – he’s worked on all four Jurassic Park films – the idea of genetically splicing dinosaur species together is extremely fanciful.

The real process of ‘digging up dinosaurs and putting them back together’ (to quote a library book I read about a bazillion times as a dinosaur-obsessed child) is more like trying to assemble a jigsaw puzzle that’s missing half the pieces. Since the field of palaeontology emerged in the late 18th century, our understanding of how dinosaurs looked, stood, moved and behaved has changed radically, as researchers find new fossils and use more advanced techniques to reassess pre-existing ones. Dinosaurs today look so different from the visions of my childhood that they almost are new animals.

Fossil finds in southern England and Germany during the 19th century formed our earliest ideas about dinosaurs, followed by the American excavation boom that’s been dubbed the ‘Bone Wars’. Unearthed in New Jersey and unveiled in Philadelphia in 1868, Hadrosaurus foulkii was the first ever mounted dinosaur skeleton, and until 1883 it was the only mounted dinosaur on display anywhere in the world.

Hadrosaurus was mounted in a bipedal, Godzilla-style pose, with a low, dragging tail. (Source: Wikipedia)

But today, palaeontologists believe most plant-eating dinosaurs were quadrupeds, with their necks and tails held aloft, and their spines parallel to the ground. (Source: Wikipedia)

With so few points of comparison, dinosaurs were imagined as archaic reptiles that had become extinct because they were heavy, sluggish and cold-blooded. This philosophy dominated palaeontology until the ‘Dinosaur Renaissance’ that began in the 1960s, which argued instead that dinosaurs were swift, smart, warm-blooded creatures who’d been wiped out by a catastrophic meteor impact.

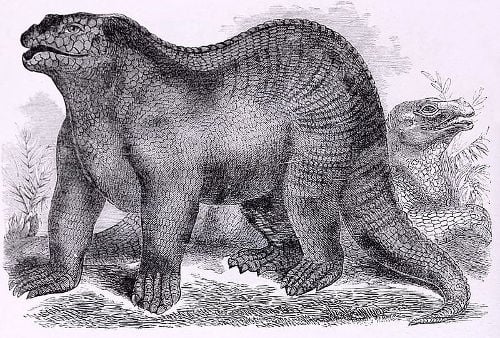

Iguanodon, one of the earliest discovered dinosaurs, was first known only from its teeth. It does not look anything like this 1859 illustration. (Wikipedia)

And, thanks to another upright 19th-century skeleton mount, Iguanodon was depicted as some kind of palaeo-Fonzie well into the 1980s. (Wikipedia)

Other well-known skeletons, such as the Smithsonian Institution’s Triceratops, aren’t even from one individual animal, but were pieced together from multiple animals of different sizes. 3D scanning and printing technology – which is revolutionising palaeontology – now enables researchers to experiment virtually with new poses, to resize bones up and down, and print bones to replace missing ones.

Early mounts also didn’t allow space for soft tissues such as cartilage. Recent studies comparing ostriches and alligators to dinosaur skeletons have revealed that dinosaurs are much taller than previously thought – Tyrannosaurus rex stood at least four metres.

Real Dinosaurs Were So Much Weirder Than Moviegoers Expect

Palaeontologists have actually been disappointed by how conservatively Jurassic World depicts its dinosaurs. Based on imprinted textures in ancient clay and amber, and the knobs on bones where quills were attached, scientists have known for quite some time that some dinosaurs – including iconic ones, such as T-rex and Velociraptor – had fur and feathers. Others had keratinous knobs, horns and spines, or membranes and frills of skin.

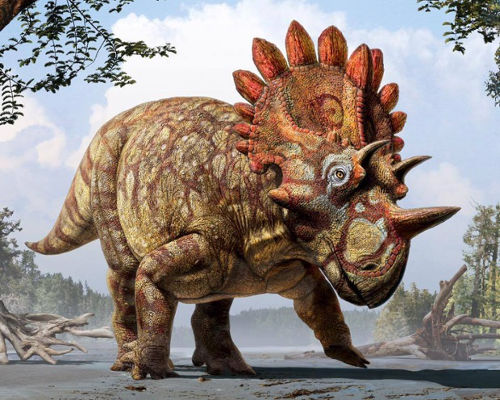

Crazy new dinosaurs are being discovered all the time. Just last week, the discovery in Canada of ‘Hellboy’, an even more elaborately horned and frilled cousin to Triceratops, was reported in the journal Current Biology.

Regaliceratops peterhewski actually got its comic-book nickname because it was super difficult to excavate. (Art by Julius T. Csotony, of the Royal Tyrrell Museum)

And in April, Nature announced the debut of Chilesaurus diegosuarez, a weird little creature discovered on a Patagonian hillside in 2004 by seven-year-old Diego Suarez. This Jurassic biped, about the height of a large dog, is closely related to T-rex but was vegetarian, and had feet more like those of long-necked dinosaurs. If Diego hadn’t found such a complete skeleton, scientists might not have realised all these features belonged to the one species.

Chilesaurus is like a platypus in the way it combines anatomical features otherwise seen on several different animals. (Art by Gabriel Lio for Smithsonian)

The trouble is that pop-cultural portrayals of dinosaurs tend to lag behind the science, because they stick to what people already expect. This explains why some of the books I read as a kid still depicted portly, upright lizards with bent elbows and ‘bunny hands’ rather than the dynamic, action-packed illustrations that inspired Michael Crichton.

Even today, depictions of dinosaurs tend to look streamlined and ‘shrink-wrapped’ rather than portraying the fat, muscle and soft textures the fossil record tells us would have been there.

The book All Yesterdays, by palaeozoologist Darren Naish, with illustrations by palaeoartists CM Kosemen and John Conway, works with fossil evidence but disrupts representational clichés. It shows a T-rex curled up asleep like a cat, a Stegosaurus having sexasaurus, and Protoceratops climbing trees like goats. Importantly, the book also uses the familiar tropes of dinosaur art to depict familiar animals such as cows, swans and cats in weirdly alien ways – suggesting the limitations of working only from skeletons.

Jurassic World is especially hampered by its need to maintain the look and feel of the previous movies. Yes, the dinosaurs probably should have had feathers. But the whole Jurassic Park story is one of hubris: it warns us that ancient creatures can’t be completely understood or controlled. There’s so much we still don’t know about dinosaurs.

–

Jurassic World is released nation-wide on Thursday June 11.

–

Mel Campbell is a freelance journalist and cultural critic. She blogs on style, history and culture at Footpath Zeitgeist and tweets at @incrediblemelk.