The X-Men Have Always Been Queer Superheroes, You Just Weren’t Paying Attention

Gay! The secret homosexual agenda in The X-Men.

There aren’t many superhero teams as iconic as Marvel‘s long-running band of misfits, The X-Men. Since 1963, they’ve been fighting evil in a world that hates and fears them — and along the way they’ve been a big old beacon of queerness. The X-Men are a powerful metaphor for gayness, without their creators really even realising why.

The X-Men belong to the gays.

Over the long-running comic books, cartoons and films, we follow the “Homo Superior”, or mutants: a group of gifted (or cursed) youngsters with special abilities like telekinesis, and beams of light shooting from their eyeballs. They are hated, hunted and controlled by the general public for the way they look, and their powers.

The X-Men has told a tale of resilience and self-identity. A tale that is distinctly queer, despite lacking actual queer characters.

The X-Men are really gay

— dedhurs Rambly (@lucasbavid) September 19, 2018

Queerness Is Like A Very Horny Super-Power

Just like young queer people, mutants usually discover their identities and unique abilities when they’re in their teens, at a time when they’re alone and scared, and vulnerable. Mutants also have to come out to their family, and the response often is fear and ignorance.

Don’t believe me? Watch Bryan Singer’s original X-Men film trilogy — especially the X-2 scene where Bobby ‘Iceman’ Drake comes out to his parents as a mutant. Instead of being supportive of their son and his gift, his family straight-up asks “if he’s tried not being a mutant?”. The only support Iceman has is from other mutants — just as young queer people alienated by their loved ones often find a new home within the queer community.

Look, what I’m saying here is that it’s not hard to see the parallel to the queer experience of coming out, okay?

Although gays rarely get together to fight crime. Which is a shame, really.

X-Men is a great gay parable but if you go with that then the first movie is about Magneto having a super weapon that makes people gay.

— Harvey Mutton (@theharveymutton) September 21, 2018

A Metaphor For The Persecuted

Most conflict in the X-Men universe originates from a clash of ideals between former best friends Charles Xavier and Max “Magneto” Eisenhardt.

The two planned to create a safe place for mutants, but their different attitudes in how to do that exactly (working with humans versus shooting them with magnetic powers) led them to create their own separate communities.

I just heard the X-Men be defined as very structurally gay and that is a phrase that finally puts words to a thing I’ve been trying to describe.

— (((Derek L. Chase))) (@DerekLChase) September 20, 2018

The idea of a battle for a safe space for minority groups meant that an analogy between X-Men and the civil rights movement in the US was initially made, admittedly through the rather hyperbolic lens of the comic-book world. Creator Stan Lee even said that the X-Men were “a good metaphor for what was happening with the civil rights movement in the country at that time.”

However, despite the creators’ intentions, it’s a pretty problematic comparison to keep making. So let’s not do that.

I know x-men were created for as a civil rights movement metaphor but damn does feel like a perfect description of the queer experience.

— 🦖Julie the Godzilla Enthusiast🌈(She/They) (@TrexPushups) September 18, 2018

Likening the super-villain Magneto to Malcolm X isn’t the best idea, but the metaphor does continue to persist when describing the queer community, in a much less problematic way. It projects fears and worries from the real world into dystopian scenarios, which can serve as rather grim warnings.

In the comic series, Days of Future Past (Uncanny X-Men #142-143), writer Chris Claremont warns of a future where the government passes a bill to know the whereabouts and powers of all mutants, triggering a period of anti-mutant hysteria and mutant internment camps. X-Tinction Agenda (Uncanny X-Men #270-272) sees a world run by an anti-mutant regime as the X-Men and X-Factor unite to save the New Mutants team from genocide and start a revolution, telling a powerful story of queer resilience and empowerment.

You know, light-hearted comics stuff.

Claremont represented a powerful point in the Marvel Comics franchise, where mutants were no longer merely a metaphor for a minority but explicitly and provocatively gave a voice to people experiencing racial and queer profiling and oppression.

A Queer Legacy (Virus)

The X-Men’s creators transformed key moments in queer history into powerful inspiring metaphors.

After Claremont left in 1991, Marvel Comics began to adapt even the darkest moments of queer history, taking inspiration from the effects of the AIDS crisis on the LGBTQI+ community. Introduced in X-Cutioner’s Song (X-Force #18), the Legacy Virus was a devastating plague affecting mutants that once infected would disrupt the production of healthy cells, and eventually lead to the victim’s death.

Writer Hana Koutnan puts forward the criticism in her thesis A Queer Reading of Marvel Comics that the Legacy Virus story arc mirrored some of the ugly conversations that spiralled during the HIV epidemic, encouraging hate and fear. Echoing conspiracy theories that the HIV was produced by the US government, the Legacy Virus was first created as a bioweapon against mutants and deemed the “Mutant Plague” just as HIV was considered the “Gay Plague”.

Unlike other X-Men comic storylines, no other Marvel comic book franchise explored the consequences of the Legacy Virus, implying it was a strictly mutant or queer issue.

Once the virus infected the human character of Moira MacTaggert, a cure was shortly discovered, making the message of the story, as Koutna puts it: “there is no hurry to find the cure until the “normals” are in danger.”

You Can Always Be More Gay

So you get it by now, yeah? The X-Men, every step of the way, is one great big gay metaphor. So you’d think there’d be a bunch of actual queer characters. LOL, nah.

It wasn’t until 1992 when the character of Northstar came out (Alpha Flight #106) that Marvel Comics began to represent queerness publicly. And then, of course, the character quickly showed symptoms of HIV, painting a needlessly stereotypical image of queer people for the first time in the Marvel universe.

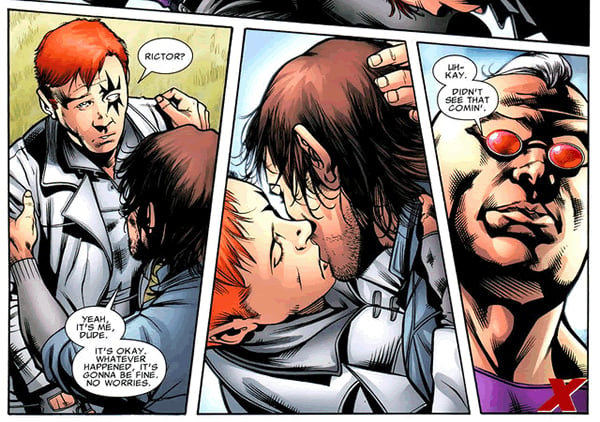

Oh, and even though X-Factor team members Shatterstar and Rictor first appeared in the 1980s, they didn’t even kiss until X-Factor #45. That was 2009. It was also the first same-sex kiss in comic book history.

Fast-forward to 2015’s All-New X-Men, teens from the original X-Men team (Cyclops, Beast, Jean Grey, Iceman and Angel) are brought to the present day to deal with their corrupt current selves (it’s a comics thing). Jean Grey coming to terms with her new telepathic powers, reads the mind of young Iceman and publicly outs him as gay. Needless to say, he’s a bit uncomfortable with the whole thing.

In true time-travel storyline fashion, present-day Iceman wasn’t already confirmed gay. So making the teen Iceman question his sexuality read as either a continuity error or an issue in how writer Brian Michael Bendis understood sexuality.

The X-Men franchise made history as being the first mainstream comic book publisher to represent queers in mainstream comics. But it was failing to treat these stories as important as it had its heteronormative romances.

The Golden Age Of Queer X-Men

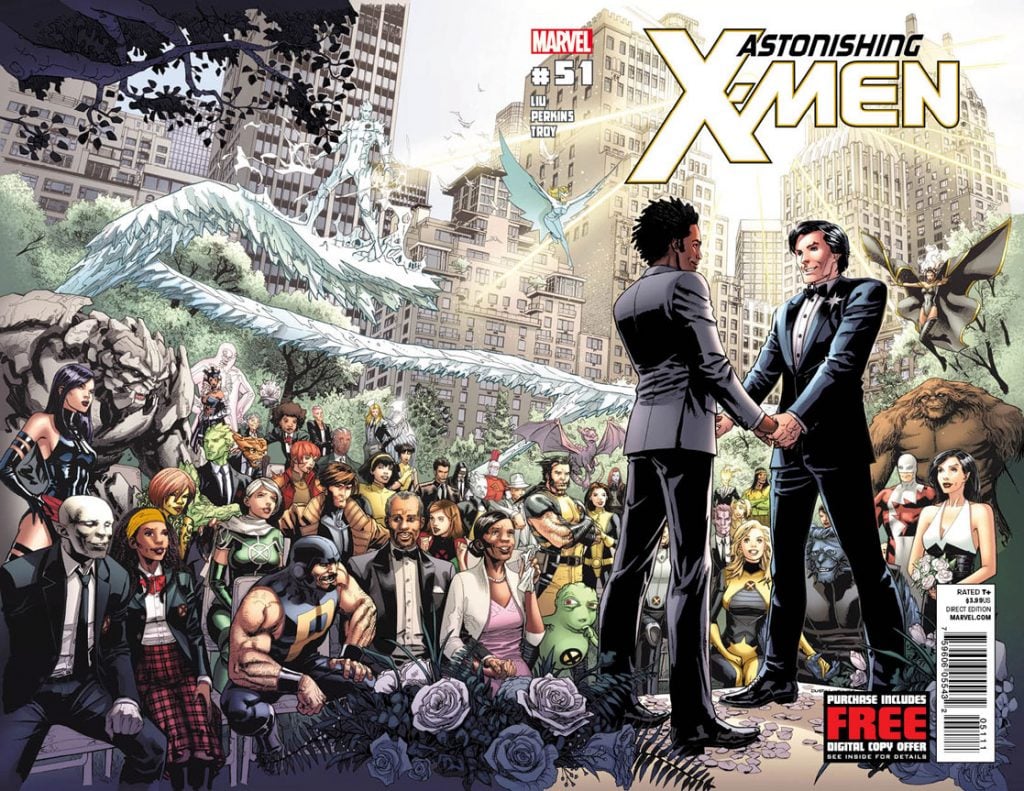

In 2012, Marvel Comics featured the first same-sex marriage in a superhero comic (Astonishing X-Men #51), where their first gay mutant Northstar wed his long-term partner. It signalled a change for Marvel, telling stories that explore queer mutants outside of their shiny yellow spandex suits.

Sina Grace’s Iceman (2017) tells the adventures of newly-out original X-Men member Iceman (both past and present versions) as he comes to terms with his sexuality and dating in the mutant world — while fighting some of the biggest enemies in the X-Men universe. It was cancelled after three volumes.

Kieron Gillen’s Young Avengers (2013) features a team made up almost entirely of queers. We’re talking Scarlet Witch’s son Wiccan and his shapeshifting boyfriend Hulkling, a genderfluid Loki and the bisexual universe-traveling Latina heroine, America Chavez.

As a reflection of the more progressive twenty-first century, the Marvel Comics world now sees mutants as Avengers, really. Loveable known public identities, no longer defined by their mutant genes. We are seeing an exploration beyond metaphorical mutant identities. Marvel Comics are explicitly writing about the X-Men’s queer backgrounds.

There’s more work to be done, but it’s such a good start.

Marvel will have character like Dooo on the X-Men line up before an out trans person? A member of the brood can be on the team but no trans people? For all the queer allegory of X-men they are dropping the ball on trans visibility. #sjwmagneto

— Krakoan Buzzkill ( they/them) (@sjw_LauraKinney) September 19, 2018

The X-Men universe once told a story of overcoming fear, exclusion and isolation that only resonated with struggling young queer geeks. Despite a lack of genuine queer representation, it now is a reminder of the more expressive and openly queer times we live in.

The X-Men Universe is acknowledging the rich history of queer culture it has drawn from.

—

Hey, just FYI, if you buy something from one of the links in this article, we may earn a small commission.

Julian Rizzo-Smith is a friendly neighbourhood queer freelance writer reporting on pop culture, games and entertainment. He is an avid fan of the femme fatales of Marvel Comics and dreams of a world where all his favourite superheroes are queer. You can find him sharing his freshly hot takes and puns on pop culture, queer discourse and general geek things @retawes.