"In these uncertain times..."

If you've received an email in the past couple of months, you've likely read those words.

"Like you, we're keeping an eye on the latest news and updates during this emergency..."

So rapid and novel have the rules and advice changed, it was enough to make your head spin. The world descended into chaos, weighing on your wellbeing, withering your physical, mental and emotional health.

"We're taking the time to check in on you during this unprecedented crisis..."

Of course, all those online stores really do care about your wellbeing. And so, in this uncertain and unprecedented economic/health crisis, have you actually asked yourself how you're going?

"There was definitely a fear that I would be stood down all together and not have anything," Kathryn Stevenson, who works in professional sport, told Junkee from her Melbourne apartment.

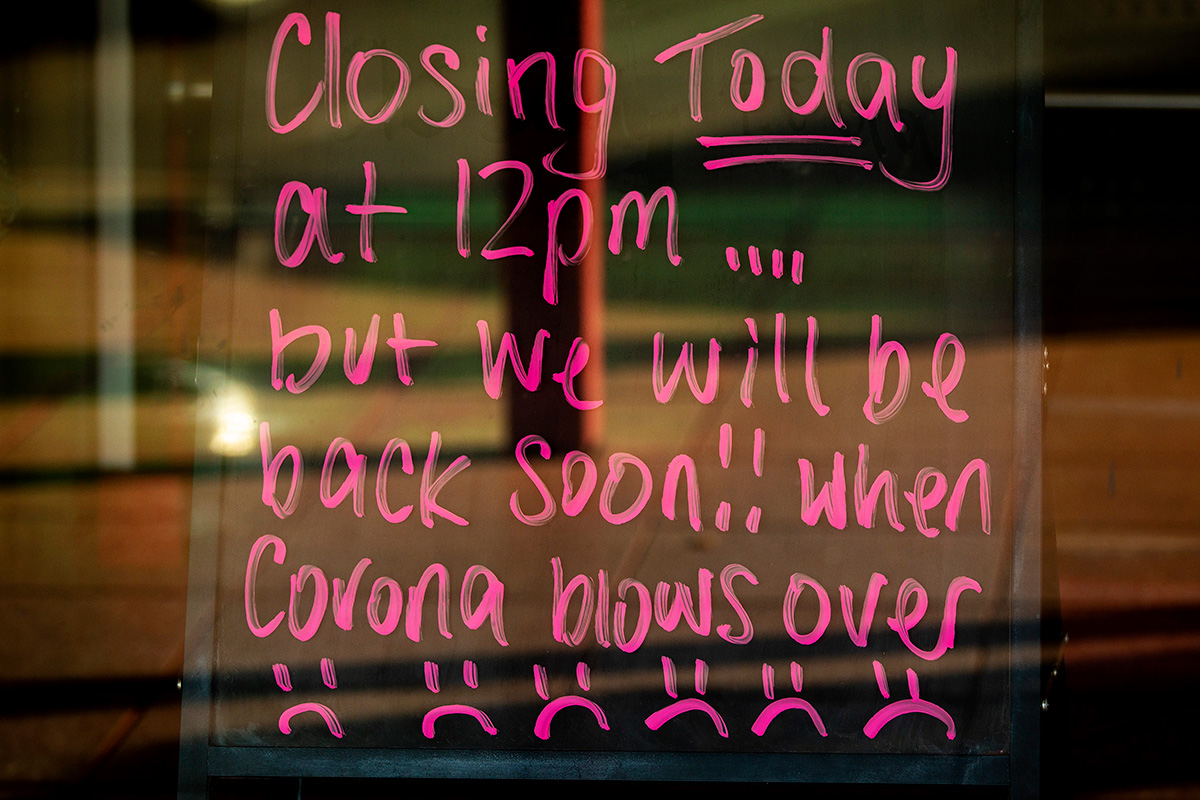

When the Coronavirus hit Australian shores, Kathryn's income looked uncertain. Like many young Australians, the 31-year-old works in a highly social industry that looked certain to close as the world went into suspended animation. Travel and games were called off, and it looked like many of Kathryn's weekly functions would be called off, too.

As reality changed daily, Kathryn didn't know how badly her income would be hit.

"Not only was there a fear that there might not be enough work, but there was also a fear that there would be just enough work to disqualify me from government help... but not enough to keep me going; that I would end up in between," she said.

"It felt constant, a constant low. Sometimes higher-level stress or worry... I would say to myself. 'I can't do anything to control it, it will be OK'."

The coronavirus has been a tandem medical-economic threat to Australia's young people. None had the antibodies to withstand the spreading novel virus. And given the way certain industries attract young workers – hospitality, entertainment, retail – many would struggle in a sharp and sudden economic downturn. Whether The Youth had enough resilience for such hard times remained to be seen.

Our grandparents and great-grandparents, those who lived through the Great Depression, never forgot it. They scrimped and saved; reused everything, threw away nothing. The hard times built up resilience through frugality.

But our simultaneous global pandemic and economic downturn is novel, unknown, unprecedented. For governments around the world, responding to the medical/financial COVID-19 crisis has been an experiment of sorts, and no response perfect.

“Not only was there a fear that there might not be enough work, but there was also a fear that there would be just enough work to disqualify me from government help.”

Professor Julie Leask of the Sydney Nursing School and visiting fellow at the National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance (NCIRS) said a lot of creativity goes into pandemic planning, describing it as "an art and a science".

"The first rule in risk communication is to prepare pathways to communicate rapidly with all stakeholders and see it as a two-way process," she said, suggesting that while communication has occurred in Australia, "there have still been multiple gaps".

In Australia, medical responses have seen infection and mortality rates contained. But financial measures have seen millions fall into government assistance grey zones. More than a month after the JobSeeker and JobKeeper packages were announced, communications gaps meant many were uncertain whether they qualify for assistance.

According to survey data from jobs platform Indeed, one in five Australian workers lost their entire income in March, with the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) estimating almost one million people have lost work since social distancing measures were introduced.

An organisational psychologist working in people and culture, part of Kathryn's job was delivering bad news about reduced hours to colleagues.

"I continually reminded myself of that," she said. "I knew I was never going to end up on the street. But that has been a realistic prospect for many people."

A recent survey of the financial wellbeing of young Australians, conducted by Junkee in partnership with ANZ right before the COVID-19 crisis found those who thought it was "somewhat likely" their situation would change in next 12 months were also less likely to have money left over after covering their expenses. If their situation did change and they were suddenly jobless, those same respondents said they would only last between one-to-four weeks before having to borrow money.

No-one can plan for the unknown. But be it unemployment, a pandemic or an economy-wide downturn, how we weather any storm depends on how much resilience we'd built going into it.

Beau Damon worked for a Hobart-based start-up but was stood down in March as exports "came to a grounding halt".

An e-commerce, branding and communications manager, he was set-up to work remotely from his girlfriend's house in Melbourne so they wouldn't be cut off from each other as social distancing measures were ramped up. Tasmania was pulling up the drawbridge. Returning meant two weeks' hotel quarantine.

“I knew I was never going to end up on the street. But that has been a realistic prospect for many people.”

"Unfortunately, the business circumstances changed quite rapidly. Quite unexpectedly, my position was null and void," he said.

Now "displaced due to the pandemic", Beau has been searching for freelance work while waiting for JobSeeker assistance. A month had passed since he was sacked. Beau had some savings, but said "it's difficult to press pause on everything and expect [it] to be fine".

"I wasn't in the ideal position to be prepared for an economic shock such as this," he said. "But I imagine there [are] people who are much worse off."

To survive, Beau has regressed to his frugal former self; when he was "on that pathway, working shitty jobs through and after school, living on rice and beans for a long time".

"It's kind of like you're a uni student again," he said.

He buys cheap takeaway curries, boosting them with more chickpeas, "giving it a new life... turning those two meals into four...something that I wouldn't have been doing two months ago".

"I'm pretty resourceful. They call me 'Beau Grills'. The mindset switches to sink or swim. There's a shock in terms of a certain lifestyle that had to be shifted," he said.

Central Queensland University's Olav Muurlink, who heads up UCQ's course in sustainable innovation, said it's natural that people "become addicted" to new levels of comfort when their wages and socio-economic status rise.

"In times of prosperity, we rarely think of preparing for adversity."

"Humans are creatures of habit," he said. "And if they get into a zone where there is always a steady wage coming in of a certain amount, they become addicted to that wage."

For someone like Beau, going from struggling student to start-up lackey meant falling a rung or two was not so great a tumble. When those at the top of the heap, enjoying a life of luxury, are suddenly and unexpectedly stretched well beyond their means, the fall can be far, fast and hard.

"In times of prosperity, we rarely think of preparing for adversity, [much less] come up with a back-up plan, and a back-up plan for that back-up plan.

"We tend to base our thinking about the future on our understanding about the present and the past, and our understanding about the present is biased by the fact that we only have access to a very tiny portion of the information we need to know about the world around us."

Dr Jo Lukins, a Townsville-based psychologist who has taught resilience and high performance over her 25-year career, said the challenge of COVID-19 is in the "circumstance that most people couldn't have anticipated".

She said it serves "as an important reminder to have planning in place to be regularly looking after our finances and health so that, when we are challenged, we are better resourced, financially in a better position, and have greater physical resilience to manage it".

Nate Vumbaca spent a month travelling South Korea around Christmas when the COVID-19 crisis started to ramp up. Nate returned to work, ready to save up for his next big adventure. He wasn't planning on unemployment.

"I work as an event producer," he said. "Which means I no longer have a job... That did not leave me in a good spot financially," he said of the holiday that seemed an age ago. "I'm definitely counting on that JobSeeker payment to come through very soon."

The 27-year-old Sydneysider and his colleagues were "prepped bit-by-bit" as whole industries shuttered.

"Then they started making cuts by rounds," he said. His team went from six to one, "and I was in the final round".

The health challenges of the COVID-19 crisis are proving more deadly for older Australians, but younger Australians are bearing the chronic financial burden – now and into the future.

Young workers aged 15-24 are "more exposed and more vulnerable to the impacts of the pandemic on the labour market than are people in older age groups," the ANZ Economic Insight Report from late April found. It states hospitality, retail, and the arts and recreation industries "have the highest proportions of young people in their workforces [with] 45 percent of young workers employed in these three industries".

More than half of young workers in Australia are casual. An estimated one in four young workers are casuals who have been with an employer less than 12 months. That disqualifies them from JobKeeper, but the Morrison Government has shown no sign of budging on that. With youth-dominated industries in a "medically induced" COVID-19 coma, young workers wait anxiously at the bedside for signs of life.

"It's definitely ravaged quite a lot of the industry," Nate said. With no income and no clarity whether they qualify for JobKeeper or JobSeeker payments, many of his broke colleagues and friends have moved home.

In the uncertain three-and-a-half weeks since Nate was stood down, waiting for word on the dole was "quite an anxious position to be in".

"It all seems confusing, a little bit more confusing than it needs to be," he said, blaming government confusion for the uncertainty.

Searching for answers, Nate was reading lots of "mainly COVID-19" news. He was not alone. According to Nielsen, 18-to-29-year-olds nearly doubled their weekday time on news sites from February through March, hunting for updates. Over the same period, people aged 30 to 39 years more than doubled their news consumption. Four out of five stories were COVID-19-related in March. As the hardest-hit demographic, millennials turned to the financial pages.

"While everyone is concerned about the financial future post-pandemic, millennials are the most engaged with financial content," said Monique Perry, managing director of Nielsen Media.

“[COVID-19 serves] as an important reminder to have planning in place to be regularly looking after our finances and health so that, when we are challenged, we are better resourced, financially in a better position, and have greater physical resilience to manage it.”

"Whether that's good or bad, I'm not sure," Nate said. "I guess for the other side, to be ready when this does start to even out, I want to be prepared to be ready financially and in the industry I work in." Nate is "keeping an eye on the numbers and industry-related news", looking for a turning point. He knows the "bounce back won't come instantly", but how long that takes could mean a complete career change.

"Maybe I can sit around and watch Netflix for the next month and everything will go back to normal," he said. "Maybe I'm still in denial."

Unfortunately, said ANZ economist Adelaide Timbrell, the youth-dominated industries that shut down fast will reopen slowly.

"We're not expecting to get out of lockdown on day one and have everyone go back to their normal dining-out spending on day two," she told Junkee.

"That means industries [of which] young people are a big part [fall] into that discretionary category; all that fun stuff that people want to spend money on when they do have money to spend."

COVID-19 is a "unique situation which makes it really hard to predict what's going to happen once we come out", Timbrell said. "We're going to see more of a slow recovery [in] hospitality, retail and those key young workforces once we have snapback," she said.

Meanwhile, Nate is doing his best to keep spending low to cover rent and bills, but admits it's "not a fun feeling to watch it decrease quite steadily".

According to Junkee's financial wellbeing survey, an alarming number of respondents did not favour their chances if they found themselves suddenly jobless.

Asked "How long would you be able to financially sustain yourself and your lifestyle without having to borrow if you were suddenly unable to work?" Twenty-seven percent said they could survive between one and four weeks. Nineteen percent said they could last up to three months. Sixteen percent would only last a week.

Being unprepared for the unknown is only human, but it's more pronounced in young people, said Michelle Baddeley, a professor in behavioural economics at the University of Technology Sydney.

"There is evidence from psychology and behavioural economics that younger people are more likely to take risks, and less likely to think about the future," she said. Within the current crisis, Prof Baddeley said "healthier and stronger" young people might be more inclined to risk illness or trouble with the law because while those costs are longer term, "the benefits of fun with friends are immediate and tangible".

"There'd be a rational basis for this, too, because social connectedness with larger groups of people is something that's more important to younger people who are less likely to have settled into a family unit," she said, adding that young people are more driven by "social rewards" than older people.

For millions of young Australians denied social interaction and the chance to work, the sense of loss is doubled. If we deny them government support too, it's hard to suggest young people aren't making multiple sacrifices.

ANZ's Adelaide Timbrell said while "there are gaps" in the Morrison Government's responses to the COVID-19 crisis, the overall effect of JobKeeper and JobSeeker supplements "is going to reduce the unemployment rate compared to what would happen if we didn't have that stimulus".

“There is evidence from psychology and behavioural economics that younger people are more likely to take risks, and less likely to think about the future.”

"Certainly, the gap of casual workers that are employed in less than 12 months is going to be affecting younger people more than it will older people, who are less likely to be in that position," she said.

Timbrell said the Morrison government's quick and dirty response to a fast-moving crisis meant perfection was out of reach.

"There are gaps everywhere, with the social distancing rules, within the stimulus, and one of those gaps happened to affect young people a lot more than it affects older workers," she said. "But it's certainly not the only gap. It's because those policies have had to come [into effect] really, really quickly."

For the young and jobless, planning amid uncertainty is an impossible feat.

Ebony Beby was planning on moving to London before everything "flipped on its head". The 22-year-old had been saving and planning for 18 months before COVID-19 closed borders and ports.

"Obviously, [when you're] planning to move overseas and you're getting ready and all set up, I had to save up quite a lot of money," she said of the long, expensive visa process. Relocation plans set, Ebony opted for a nine-month contract with oOh! Media (Junkee's parent company) that ended right before she was due to fly. The good news is she had a financial cushion to soften her landing when the contract ended. The bad news is her pillow will shrink the longer her plans are in limbo.

"Yes, I have savings, but if I can't find work or don't have an income for the next year, it means I have to dip into that money and all my plans are pushed further back," she said. "Potentially, I can't live out my dreams for – who knows? Six months? Three years? I have no idea."

Not even the Prime Minister knows. At the end of April, as states prepared to ease restrictions on certain aspects of Australian life, Scott Morrison said the dangers that come with overseas travel were still too great.

"I can't see international travel occurring anytime soon," he said at one of the semi-regular coronavirus crisis press conferences. "The risks there are obvious."

The world's problems blocking her path, Ebony was resilient.

"I'm young and still have plenty of time, but when you think that you have everything in front of you and [are] ready to conquer the world, it takes its toll on you."

The COVID-19 crisis is taking a toll on all of us in one way or another. But we can all take precautions to limit the impact.

Dr Joann Lukins, author of The Elite: Think Like An Athlete, Succeed Like A Champion, said how we respond to unpredictable adversity, and our "ability to rebound", starts with steeling our minds, emotions and bodies.

"The way we speak to ourselves matters," she said.

"One of the greatest challenges for people is when life feels out of control and unpredictable. The other challenge is that, while COVID-19 is ongoing as a crisis, it can feel challenging to respond."

“Potentially, I can't live out my dreams for — who knows? Six months? Three years? I have no idea.”

Dr Lukins said there are four main pillars of personal resilience: physical resilience (exercise, eating well, staying hydrated and getting adequate sleep); emotional resilience (staying active, staying engaged, but not always staying indoors); mental resilience (challenging yourself with puzzles, crossing off lists, problem solving, mindfulness and gratitude). The fourth pillar is social resilience (talking with friends, spending time with others, helping others), which, Lukins admits, is the hardest to maintain in our current circumstance. "That way, we can draw upon a range of skills that might be helpful," she said.

How prepared you are to manage challenging times could depend on how well you manage your personal finances. But how well you budget could be something that was ingrained in you well before you knew what a budget was.

In the famous 1972 Stanford Marshmallow experiment, child subjects were given the choice of one marshmallow now, or two if they waited. Motivated and able to delay gratification, those who waited went on to lead successful lives, so the story goes.

Four decades later, the University of Rochester's Baby Lab recreated the experiment. Only this time, before asking the young subjects the "marshmallow question", researchers told the children they could play with a worn-out and used-up set of crayons or wait a little bit for some better ones.

That divided the group in two: reliables and unreliables. When the reliables waited, they got the new set of art supplies. When the unreliables waited, they were told there was nothing better coming. When the researchers asked unreliables to wait and trade their one marshmallow for several more, not wanting to get burnt again, they did not delay gratification.

"If you are used to getting things taken away from you, not waiting is the rational choice," said Celeste Kidd, lead author of the study and now professor of psychology at the University of California, Berkeley. "Then it occurred to me that the marshmallow task might be correlated with something else that the child already knows, like having a stable environment."

Those early lessons can set you up for life. Unfortunately, there are no great school lessons in financial planning or banking. Like the good crayons, some of us get lessons in budgeting, but many don't.

“Those early lessons can set you up for life. Unfortunately, there are no great school lessons in financial planning or banking... some of us get lessons in budgeting, but many don't.”

Of the 4517 surveyed by Junkee, 66 percent have budgets; 60 percent have weekly, fortnightly or monthly budgets; four percent have daily budgets. Forty-nine percent of those surveyed said they stick to their budget all or most of the time.

Other than a few high school math lessons about the functions of money, Nate Vumbaca said his financial education came mostly in adulthood – through some hard life lessons. "That was a real big, steep learning curve, once I got into the workforce," he said, disclosing that "lots of mistakes were made really early on with banks".

"No-one teaches you that. You figure it out, but a lot of it is just by making mistakes and learning from them," he said.

Even though Ebony Beby started working as soon as she was legally allowed, her schooling "didn't have a lot of coverage of finance, or living in the big, bad world".

"I have one memory from when I was in probably Year 10, toward the end of the school year, off the net," she recalled. The lessons weren't official curriculum, but an end-of-term short course set by a teacher who took initiative, seeking online materials on tax and penalty rates. It was relevant, but rushed.

"That was the only time I remember learning about it," Ebony said. "I never really had one source that said, 'Hey, Ebony, this is how a bank account works'... It wasn't until I got into the workforce that I really learned budgeting."

In the Stevenson household, money matters were taught early, with methods passed down through generations. The names changed, but the concepts were consistent.

"We had the 'bags of cash'," Kathryn said of her family's method of dividing incomes into separate amounts to build a budget.

"I learnt that my grandmother used to take my grandad's cash and she would have physical envelopes that she would divide [it] into," said Kathryn, who has since embraced the contemporary concept of "bucketing" her money.

Whether it's buckets, bags or envelopes, memorable financial lessons often come to children in the home, not the classroom. Yet the hard lessons come later in life.

Despite the financial home-schooling of her childhood, Kathryn buried herself under several thousand dollars of credit card debt as a 20-something. "[I had] this conflicting identity, between being good with money and still having to live pay cheque-to-pay cheque," Kathryn said.

The experience made her rethink her biases that people who racked up large debts were simply careless with their cash.

“Whether it's buckets, bags or envelopes, memorable financial lessons often come to children in the home, not the classroom.”

"It was really confronting assumptions about people who did live like that," she said.

Yet even after she cleared her credit card debt, Kathryn said she often found excuses to use her credit card for something. So she ditched the card and adopted the bucket system to set near, medium and long-term financial goals; planning daily expenses and having a "rainy day fund" for emergencies.

"It wasn't until I...realised there is actually a psychological benefit to knowing you're ok and have that money there," she said. "That's what shifted my mindset."

Kathryn said the notion of a "rainy day fund" is about looking toward the positive, but it could be there for the negative if those are the cards that are dealt.

For many young Australians like Kathryn, lessons in money matters come well into adulthood. So maybe the Talking Malibu Stacy doll was right: they should talk shopping in school. And credit cards. And financial planning, mortgages and superannuation.

Because even if you're convinced you have a good budget, the unexpected can and will happen. Just take a look at Scott Morrison and Josh Frydenberg. Twelve months ago, Treasurer Frydenberg stood in parliament on Budget Night claiming the national accounts were "back in the black and Australia is back on track".

The Liberal Party was so certain of its "Back in Black" message, it was selling it on mugs for $35 each as late as March, when the global economic outlook turned bleak and our new COVID-19 reality set in.

One year on, Morrison and Frydenberg now preside over a "sobering" budget deficit upwards of $140 billion this year – the largest in Australian history. "And despite the adverse economic impacts from the global trade tensions, fire, floods and drought, we were on track for the first surplus in 12 years," Treasurer Frydenberg said of the 2020 budget outlook.

The prime minister and treasurer should have read up on what the Ancient Greeks said about hubris and nemesis – that pride comes before the fall. They thought they were money masters. But life is unpredictable.

Asked why they don't budget, the two largest groups in the Junkee survey were at polar opposites in their economic ethos: those who agreed "My expenses are unpredictable" (15 percent) and "I can control my spending without a budget" (23 percent). "I don't know where to start" (14 percent) was third largest group.

Prof Baddeley of UTS wondered whether those who see smooth seas ahead could be suffering from "optimism bias", an overconfidence in the books leading people to "think they have done (or will do) better than an objective assessment of the evidence would show".

"I wonder if there is overconfidence here," she wrote in an email to Junkee. "i.e. people not as good at managing money, planning for the future etc, as they think they are."

Can you blame them? Australians had not seen a technical recession since "the recession we had to have" in 1991 and '92. No corrections, only uninterrupted GDP growth for 30 years. We were the envy of the world. With a steady hand, the good times would keep on rolling.

But there is Chinese proverb: No banquet in the world goes on forever.

That's bad news for young Australians who only just got a seat at the table. For the 1.1 million mostly young casual workers in hospo, retail, arts and entertainment who don't qualify for JobKeeker, it's the starvation diet, with a side of hard times.

“There are a lot of opportunities for us to invest in the economy in a way that does support younger people who are being hit hard on the economic basis by COVID-19.”

"It is difficult to anticipate what you haven't experienced," Dr Jo Lukins said when asked how young workers could have prepared for this sudden and unprecedented medical and financial emergency. "If you've lived through a generation of prosperity, it can be hard to envisage a downturn."

But young Australians like us needn't wait for the hard lessons to learn a thing or two about finances. While you're working on your mental resilience while isolating at home, take the time to check on your financial wellbeing using ANZ's Financial Wellbeing Program, build resilience and set yourself up for the next 30 years of personal economic growth.

But ANZ's Adelaide Timbrell clarified the notion of "30 years of uninterrupted economic growth" was a misnomer because, while GDP has risen, "we certainly haven't seen equal rises in living standards in the economy over those 30 years".

"In some parts of the economy, we actually haven't seen a rise in living standards in recent years," she said.

Other indicators showed we had a sluggish economy, with 2019 household spending down from 2018; wage growth flat in many industries; high house prices making it hard to buy; low interest rates making it hard to save; massive HECS debts and rising underemployment. These, too, affect younger workers in greater proportions.

"I think the world we enter now, and for people who are entering the workforce in the last five to 10 years, is really different from previous generations," Timbrell said. "When we talk about uninterrupted economic growth, it's something where, technically, in the numbers it's there, but I think the majority of people haven't seen the benefits of that because the benefits of economic growth are not created or distributed equally."

A positive change the COVID-19 crisis might spur new economic assessments that go beyond the rosy headline GDP figures, Timbrell suggested. "I think we've started to see a wider range of indicators to assess economic wellbeing, and employment indicators has been one of those, including under-employment," the Melbourne-based economist said.

"As we go through periods like this, where people become more conscious of economic realities, hopefully we develop a more holistic way of looking at economic growth in the future."

The tiny Kingdom of Bhutan pioneered the concept of the "Gross National Happiness Index" while last year New Zealand's Ardern government introduced a "well-being budget" to get a true measure of its population's progress.

Timbrell said that, "usually after a war, or after a big financial crisis", policy-makers tend to push hard for reforms. As the economy comes out of its COVID-19 coma, Timbrell said the agenda should invest in those carrying the biggest burden: young Australians.

"There are a lot of opportunities for us to invest in the economy in a way that does support younger people who are being hit hard on the economic basis by COVID-19," she said.

Investing in renewables, improving training and education, and matching young workers to skills and opportunities should be key factors in driving the economy forward.

"I think there's a great opportunity... to make sure that young people are being prepared for the things that will really be spurring, not just economic growth, but also [to] progress of living standards [and] environmental, social and economic impacts for Australia," Timbrell said.

For out-of-work Nate Vumbaca, there is hope that something positive will come from the COVID-19 crisis.

"Moving on from this, everyone is going to start a 'rainy day fund'. I think that's going to be the biggest trend," he said.

As he awaited word on whether he qualified for the dole, he urged everyone to take time for self-care, to "put your own mask on first" and get to things you've been putting off.

"Vacuum under your bed," he urged. "It's disgusting, but you'll be satisfied."

Proudly sponsored by ANZ.

The views, information, or opinions expressed in the article are solely those of the individuals involved and do not necessarily represent those of ANZ.