How Pop-Up Stores, Origami Shelters And Bus Stop Bedrooms Are Helping Tackle Homelessness

Providing shelter and clothing to homeless people is starting to become a very creative endeavour.

It’s that chilly time of year where charities like to draw our attention to the numbers who are sleeping on the streets without a roof over their heads. Over the next three months, Vinnies, Youth off the Streets, and Mission Australia will all hold ‘sleepouts’ to raise awareness and funds for the homeless across our wide and not always so brown land, while other charities and nonprofits rock their annual winter appeals.

Australian cities are not alone in playing uneasy host to people sleeping rough or experiencing other kinds of homelessness. Indeed, it would be rare to find a city where there are not people sleeping out without a permanent home, somewhere. Which is why three groups of just-do-it types in Cape Town, Los Angeles and Melbourne have created some high-profile, street-level responses to the clothing, shelter and empowerment needs of the homeless, using the well-established language and signifiers of ‘pop-up’ retail and exhibition spaces. These ‘meanwhile’ spaces — which have previously been occupied by the ‘flat white economy’, characterised by small, niche bars and smaller, nicher cafes — are now being put at the service of those experiencing ‘primary homelessness’, who might otherwise find themselves asked to move on.

–

The Street Store, Cape Town

An open-source model founded by young employees of advertising company M&C Saatchi Abel, Cape Town’s The Street Store has been replicated in over 140 cities across the globe. Street Store hosts receive donations of clothing in good condition, which they then present with Street Store branding, before inviting people in need to come and select any clothing they like.

The organisation also encourages the public to come and hang out at their sites, to meet new people and learn about why and how people become homeless, and what they might need. As one of its founders Kayli Vee Levitan told Junkee, the simplicity and accessibility of the idea is what seemed to resonate with people: “People who want to do something to help the homeless don’t always know where to start or what people might want or need.”

You might donate clothes to a Salvos bin or tins of soup to a local food drive, but you rarely get to actually learn about the person on the other side of your donation. For a minimal cost, The Street Store facilitates a memetic feeling of global connectedness — and in the past twelve months Street Stores have been set up in cities from Bruges to Ballarat. And some enterprising young wags in Melbourne have further extended the concept, with their project HoMie.

–

HoMie, Melbourne

Having already brought us Homeless of Melbourne (an online photography and interview project aimed at listening to and sharing the stories of people sleeping rough on the streets of Melbourne), founders Nick Pearce, Marcus Crook and Robbie Gillies recently secured over 20,000 crowdfunding dollars for their new project. HoMie will occupy a pop-up space for three months in Melbourne Central, with clothes made by local designers and services such as The Streets Barber provided to clients of local homelessness services. The project’s use of concepts like the pop-up and the maker space, as well as the founders’ apparent support for the urban beard, saw HoMie dubbed by Channel Ten’s The Project as “hipsters helping the homeless.”

Now the ‘hipster’, as we all know well by now, is a label easily used to dismiss an activity as cliched or a little desperate; or, in one of its most well-worn iterations, as an aesthetic appropriation of tropes that are traditionally associated with poverty, cheapness, or abjection (think milk crate stools at cafes; jam jars as tumblers; fashion mullets; the relentless pantheon of small bars with names like Bar Economico and The Projects; and memes like Hipster Or Homeless). Critics of the hipster aesthetic might also compare activities that bolster the capitalist system with similar projects that actively contest it — consider, for example, the difference between how dumpster cafes, squatted social centres, the Occupy libraries and kitchens, and the Really Really Free Markets are treated by the authorities, as compared to council-sanctioned outdoor libraries, the supermarket-supported redistribution of leftovers, and other such projects that meet with the kind of approval garnered by The Street Store or HoMie.

Speaking with Junkee, HoMie’s Nick Pearce laughed off the “hipster” label, though he could see how the idea helps carry HoMie’s story. However it is understood in the community, Pierce hopes that their initial project Homeless of Melbourne can be a “signpost” for local people living homeless, while HoMie becomes a sustainable social enterprise “where we can one day employ staff experiencing homelessness”, and help people on their way to a stable home.

In this sense, projects like The Street Store and HoMie join organisations like 3Space (which repurposes empty spaces for use by charities and other social services) and initiatives like HomelessConnect (which connects local business and services on one site several times a year, to co-ordinate and meet the immediate needs of people living homeless) might be a promising extension of categories like the pop-up, the maker space, and the hole-in-the-wall cafe. They suggest that these new categories in urban planning, licensing, tenancy, and consumption could amount to a more social than capitalistic purpose.

–

Cardborigami, Los Angeles

Actions that seek to help others facing structural problems like homelessness often rightly face the question of whether what they’re doing ‘really’ makes a difference: whether it simply offers a band-aid solution or a feel-good exercise that won’t last; whether it’s replicating other services already being provided; and how far it considers the agency of those it claims to help. These were the questions that LA-based architect Tina Hovsepian asked herself when she developed her project, Cardborigami.

As Hovsepian told Junkee, Cardborigami started from an admittedly ‘naive’ premise: “That the thing homeless people need is homes, or at least, some shelter, a roof over their head, protection. Can’t we just do that? Create shelter where people are, where they need it?” Cardborigami is Hovespian’s design for street-based shelter: structures made of highly durable cardboard using the paper-folding principles of origami to provide shelter, privacy and protection to those sleeping rough.

But as Hovsepian quickly learned, the problem of homelessness is about much more than simply a lack of a roof. So the Cardborigami structures quickly became more of a signifier to mobilise people who, perhaps like those who would donate to The Street Store or HoMie, had a simply-felt desire to help those they see sleeping out on park benches in the cold, or asking strangers for cash. Cardborigami’s pop-up shelters are used to shelter people sleeping out, but, says Hovsepian, they are just one part of a four-step, evidence-based model designed in collaboration with the homeless and local providers of support, which takes people from being sheltered temporarily with a Cardborigami structure to being sustainably housed.

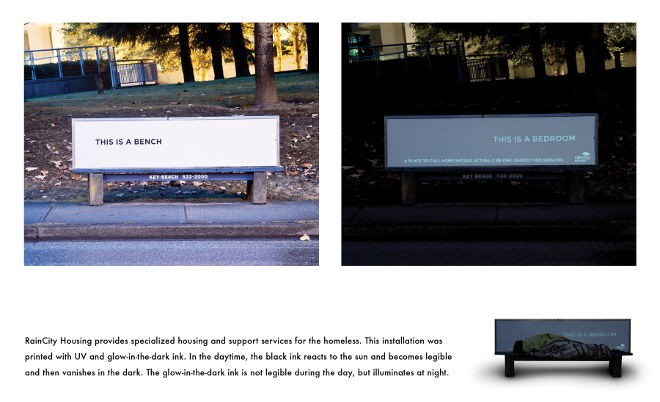

Cardborigami also challenges the phenomenon of anti-homeless ‘defensive’ architecture, a phenomenon most infamously deployed in London, where property owners install spikes in the ground to stop people from camping or resting there. (You also see it in park benches designed with dividing rails, so a person can’t stretch out on them, and the proliferation of ‘anti-poor’ or ‘victim-blaming’ laws that criminalise the homeless for ‘camping’, ‘loitering’, and ‘begging’.) In direct contestation of such measures and the attitudes that inform them, Vancouver’s RainCity Housing got Spring Advertising to develop a campaign several years ago that was centred on temporary structures that bolted onto park benches as emergency shelter for those sleeping rough. RainCity’s media spokesperson told Junkee that they still get regular requests for information about how useful the structures were to those sleeping rough, and how successful they were as a symbolic starting point for understanding what is needed to support people who find themselves without a home.

As with the pop-up services of The Street Store and HoMie, Cardborigami’s portable structures and Rain City’s street-bench shelters show that the notion of the temporary, the creative, and the pop-up might signify more than just a generalised creative opportunity. Hopefully, these projects are signs of a greater recognition that real people live in the interstices of property and public space — and that these spaces can offer innovative opportunities for cities to help their most vulnerable occupants.

–

Ann Deslandes is a writer and support worker in Sydney. She has degrees in sociology and gender studies, which makes her very annoying to watch TV with. Ann’s writing is collected here and she tweets from @Ann_dLandes.

–

Feature image via Tina Hovsepian/Archinet.