Politicians Are Responding To The Uluru Statement And It’s Pretty Bloody Disappointing

"It's not going to happen." - Barnaby Joyce

Last Friday’s the groundbreaking Uluru Statement was released. It was the result of a three-day First Nations’ conference where roughly 250 delegates overwhelmingly rejected “simple constitutional acknowledgement”and recognition in favour of an Indigenous Parliamentary body. Today our federal politicians started responding and so far… it isn’t great.

Delegates explicitly called for a First Nations Voice enshrined in the constitution, and, after hosting similar delegations across the country for the past six months, went much further than the proposed, highly symbolic referendum changes the government has considered for over five years now.

The statement came after a slightly-controversial few days of meetings between First Nation groups, where some Victorian and NSW delegates staged a walkout over the nature of discussions.

Disappointingly, although not at all surprisingly, the major party responses to the Uluru Statement have offered only slightly different levels of tepid, with Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull stressing the difficulty of constitutional change and Opposition Leader Bill Shorten bravely calling for an “open mind”.

Aboriginal parliamentarians should be treating the Uluru statement as a mandate not just something to consider. #1voiceuluru

— Gemma McKinnon (@GMcKinnon) May 28, 2017

What Are The Politicians Saying?

While a First Nations parliamentary voice and treaties process are both long overdue, the Uluru Statement is politically ambitious considering both major parties have focused on simple constitutional recognition for years now. The danger, according to both Coalition and Labor politicians, would be offering an unfeasible referendum at the cost of the minimal progress currently enjoying bipartisan support.

There will have to be "compromise" to get a "practical, pragmatic and winnable" referendum @LindaBurneyMP pic.twitter.com/UMKdldINce

— Bridget Brennan (@bridgeyb) May 27, 2017

Malcolm “Fizza” Turnbull has effectively sidestepped the call for a referendum on a First Nations Parliamentary Voice, focusing on the constitutional challenges of such as task instead of any of the specifics from the Statement itself. Speaking at a lunch commemorating the 1967 Indigenous referendum, Turnbull first explained how changes to the constitution work [cheers Malc!] before stressing that yeah, this would be a big task.

“The constitution cannot be changed by Parliament. Only the Australian people can do that. No political deal, no cross-party compromise, no leader’s handshake, can deliver constitutional change,” Turnbull said.

“To do that, a constitutionally conservative nation must be persuaded that the proposed amendments respect the fundamental values of the constitution, and will deliver precise changes, clearly understood, that benefit all Australians.”

While Turnbull confirmed that the referendum council and Parliament would consider the Statement, the fact he didn’t touch on any of the specifics, and basically told everyone they would just be super-duper hard, speaks volumes.

But…this is all so sudden!

My @smh @theage pic.twitter.com/w61QcKUp10— The Cathy Wilcox (@cathywilcox1) May 28, 2017

And while Shorten, speaking at the same event, was slightly more supportive, his call to offer Uluru delegates “an open mind on the big questions” still reeks of the symbolically appealing but practically meaningless politics delegates at the Heart specifically denounced.

Other Labor members have similarly had to grapple with the political reality of the situation. Notably, Indigenous leader and Labor frontbencher Pat Dodson congratulated the delegates but cautioned the government not to “abandon” the fives years of work already put into minimal but practical constitutional recognition, which would include a statement of acknowledgement, change race law language, and repeal an archaic ‘dead letter‘ voting provision.

“It’s fine there’s come this report out of Uluru, talking about an entrenched voice into the constitution, that will have to be weighed and considered. But I don’t think we should just dismiss out of hand the work that was done by the expert panel [on constitutional recognition],” Dodson said, referring to the panel he chaired in 2012 before entering Parliament.

“I think in the finer print of what’s come from Uluru, there seems to be … still room to have discussions about those matters.”

On each end of the spectrum we have the Greens and Nationals, with Greens Senator Rachel Siewert calling on the government to “acts on its rhetoric with sincerity and start the process outlined in the statement,” while Deputy Prime Minister Barnaby Joyce described a potential new Parliamentary body as impractical and flat out said “it’s not going to happen.”

While any new Indigenous representative body is purely hypothetical at this point, it appears as though the Joyce’s interpretation of it as a “another chamber in politics or something that sort of sits above or beside the Senate” does not correlate with the expectations of First Nation delegates.

Coming up on The World Today, Cape York Institute says @Barnaby_Joyce misunderstood Uluru meeting – it DID NOT call for new parl chamber pic.twitter.com/J7Dha1da4k

— Eliza Borrello (@ElizaBorrello) May 29, 2017

Asked @TurnbullMalcolm if it's wrong for @Barnaby_Joyce to suggest #Uluru delegates want new house of Parliament. He didn't respond. #auspol

— Dan Conifer (@DanConifer) May 29, 2017

Is The Uluru Statement Really That Radical?

The problem with the majority of these responses is the overwhelming presumption that the Uluru Statement calls for something impossible, instead of two honestly reasonable and practical outcomes.

Some context behind #1voiceuluru Statement. The reforms accord w int'l law & practice. They are not new or radical. https://t.co/wyCFfnQyko

— Dr Gabrielle Appleby (@Gabrielle_J_A) May 27, 2017

Calls for an Australian treaty have been in the works for decades, and we have examples in both Canada and New Zealand in how this could be done; again, we’re the only Commonwealth country to not have such an agreement with its First Peoples, although by the looks of it an Australian treaty has enough local support enough to rival the proposed recognition changes.

In fact, New Zealand’s ‘Treaty of Waitangi‘ both acknowledges Māori authority and ownership while also establishing a governmental voice through reserved Māori seats in the parliament.

There's nothing confusing about what came out of Uluru. In fact it was very clear. Power, treaty and a voice #insiders

— Joe (@cuz888) May 27, 2017

So while the minimalist, constitutional acknowledgement might be more politically attractive, the Uluru Statement is both feasible, long overdue, and, from the outset, electorally popular.

Unfortunately, that last one might have to be crystal-goddamn-clear before we get a major party to commit to any of the changes.

–

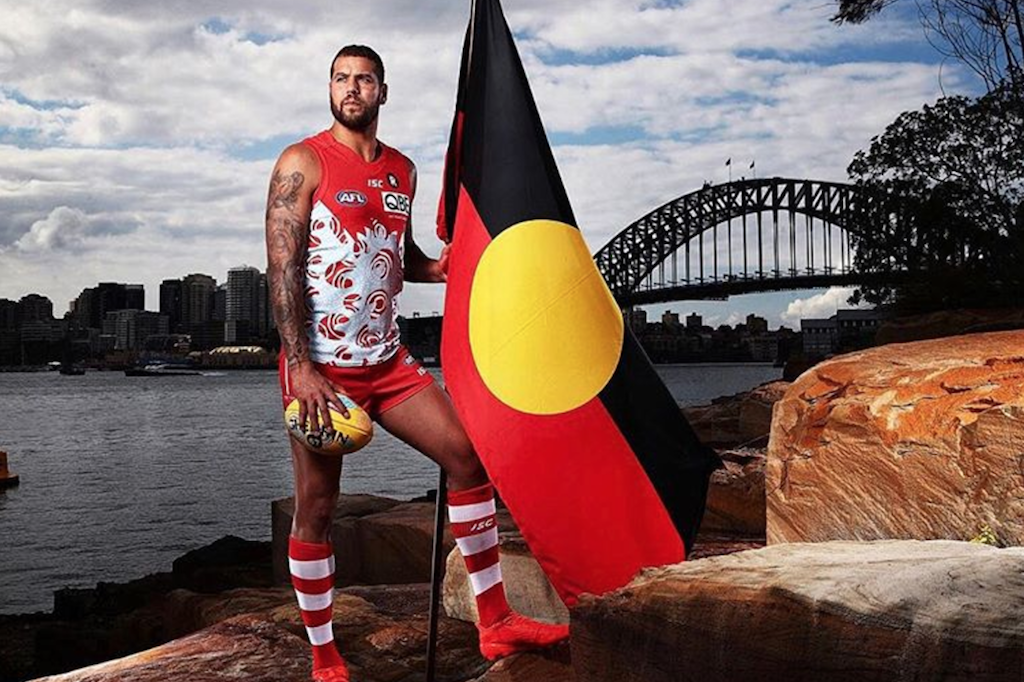

Feature image via Malcolm Turnbull/Twitter