‘Passengers’: When Waking Up In Space Isn’t Very Woke

The trailer left out one pretty important detail.

Spoiler alert: this review discusses a major plot point in Passengers.

Ten years after having emerged as one of the standout scripts on the Black List, Passengers is being widely panned. This story of two interplanetary colonists awakened from hypersleep 90 years too soon is being marketed as a romantic disaster movie – ‘Titanic in space’.

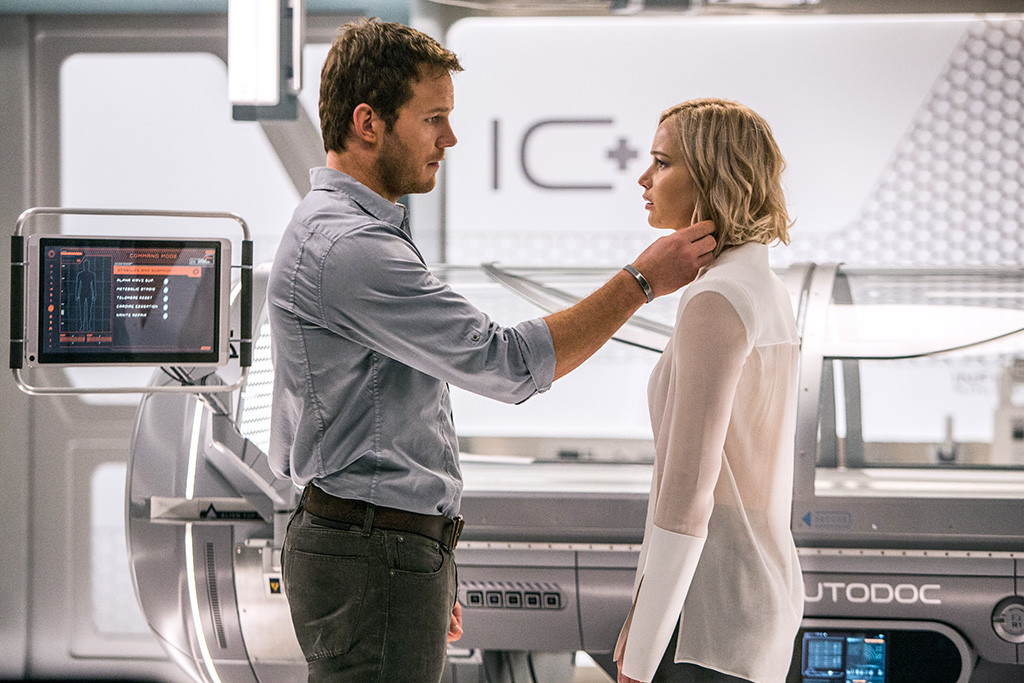

But critics are slamming it for romanticising predatory sexual behaviour; and despite the star power of Jennifer Lawrence and Chris Pratt, audiences have been avoiding it – especially women.

Meanwhile, women HAVE withdrawn their buying power from Passengers, and what’s more, we did it more or less spontaneously.

— Abigail Nussbaum (@NussbaumAbigail) January 2, 2017

However, something censorious is afoot when we accept or reject films wholesale, depending on the degree to which we’re comfortable with what they depict. I find Passengers interesting because of its problematic blundering. This is an anxious, guilty film: it understands the wrongness of the scenario it’s sketching, but can’t break away from its narrative clichés to trace a more ethical path.

–

Not If You Were The Last Man In Space

Thirty years into its 120-year voyage to the colony planet Homestead II, the commercial starship Avalon rams an asteroid field (an early clue to the film’s folkloric aspirations: Avalon is the legendary British isle where King Arthur is said to slumber). The damage seems superficial at first, but the onboard computer struggles to compensate for each error. A chain reaction of system failures begins, one of which rouses mechanical engineer Jim (Chris Pratt) from his hypersleep pod.

Of 5,000 passengers and 250-odd crew, Jim is the only one awake.

Despite his resourcefulness and technical skills, he exhausts every avenue of remedying his situation. He’s locked out of crew-only areas of the ship, and any reply to his SOS email to Earth will arrive decades too late. Jim wearies of interacting with the Avalon’s holographic and robotic information and entertainment systems. Even Arthur (Michael Sheen), the friendly barman Jim is pathetically grateful to stumble across, turns out to be an android.

At the nadir of a yearlong descent into existential despair (signified by an extremely bushy Beard of Sorrow), too craven even to kill himself in the ship’s spacewalk airlock, Jim stumbles across a sleeping passenger, a journalist named Aurora (Jennifer Lawrence). Named after the fairytale princess in Sleeping Beauty, Aurora is a New York princess: the daughter of a famous author, with lofty literary ambitions of her own. “If you live an ordinary life, all you’ll have are ordinary stories,” she explains in an interview Jim avidly watches.

And as he browses her passenger profile and reads her archived essays, Jim convinces himself that he’s in love. But I think the film is explicit in depicting Jim’s motives as base. The trailers shouldn’t have tried to obfuscate his decision to wake Aurora and then conceal his sabotage of her pod, because the drama lies in seeing an ostensibly decent person drifting towards an appalling act. Like a swimming pool in zero gravity, a waterfall in slow motion.

Passengers is interested both in the stories we tell ourselves and the violence that underlies them – which includes coercing others into participating. Like a maiden in a tower or a Belle in a Beast’s castle, we the audience are trapped in the film’s own narrative of a romance between two attractive, charming people – complete with meet-cute robots, black-tie fine dining, and a free-floating spacewalk that perversely echoes the planetarium fantasia scene from La La Land.

The stifling clichés of this romance reflect that it’s Jim’s fantasy, and that it cannot last. When Aurora inevitably discovers what Jim has done, Lawrence fairly quivers with her mingled horror, disgust and rage: “He stole my life… it amounts to murder!”

Passengers’ primary cinematic referent is The Shining (1980), Stanley Kubrick’s disturbing tale of a self-entitled writer losing his moral compass in luxurious isolation. The tracking shots of Aurora jogging through the Avalon’s glamorous, empty corridors evoke Danny Torrance on his tricycle in The Shining’s Overlook Hotel, as do the empty lounges and art deco splendour of Arthur’s bar.

But the film can’t quite nail a shift into psychological horror, or recast Jim as a sinister stalker antagonist. Morten Tyldum is just too prosaic a director, and the affable Pratt lacks Jack Nicholson’s slyness. Instead, Jim is guilty and ashamed. Several key late scenes show him supine and penitent, resigned to death now in a way he hadn’t been before.

–

The Romantic Interface Between Nature And Technology

“Jim, these are not robot questions,” Arthur says firmly as his customer agonises over whether to wake Aurora. Robot questions, however, are what Passengers does best. Far more seductive than anything that takes place between Jim and Aurora is the luxuriously high-tech environment of the Avalon itself: a massive network of human-machine interfaces designed to provide its passengers with every kind of sensory pleasure.

The outstanding production design dwells especially on the submission of human bodies to the languor of the sleeping pods and the fetishistic embrace of the autodoc – the ship’s automated medical diagnostic and treatment bay. First seen in Alien (1979) and reimagined as cellular-level magic in Elysium (2013), the autodoc’s surgical capacities were unflinchingly featured in Prometheus (2012), which was scripted by Jon Spaihts on the strength of his Passengers screenplay.

Aurora and Jim briefly discuss the way the Homestead Corporation is marketing its off-world colonies as bucolic utopias. This is the same corporation that’s so confident nothing can go wrong with its ships that its systems cannot encompass Jim’s premature wakefulness. Aurora suggests that the corporation has sold Jim a false romantic fantasy of settler life. Frustratingly, the irony that Jim is already in the grip of a romantic fantasy is never fully articulated.

Passengers’ third-act embrace of nature over the pleasurable affordances of technology reminded me of WALL-E (2008), in which a remnant human race dwells in infantilised consumer apathy aboard the starship Axiom, attended by robots, and are only truly awoken by the hopeful presence of a plant.

Jim’s and Aurora’s second-act romance is shown to be as artificial and entropic as their spaceship – doomed to break down, then explode. And it tries to redeem their connection by affirming their shared, ‘natural’ humanity. The film ends on a hopeful note; but ultimately Passengers can’t stay the course of its own cascading errors.

–

Mel Campbell is a freelance journalist and cultural critic. She blogs on style, history and culture at Footpath Zeitgeist and tweets at @incrediblemelk.