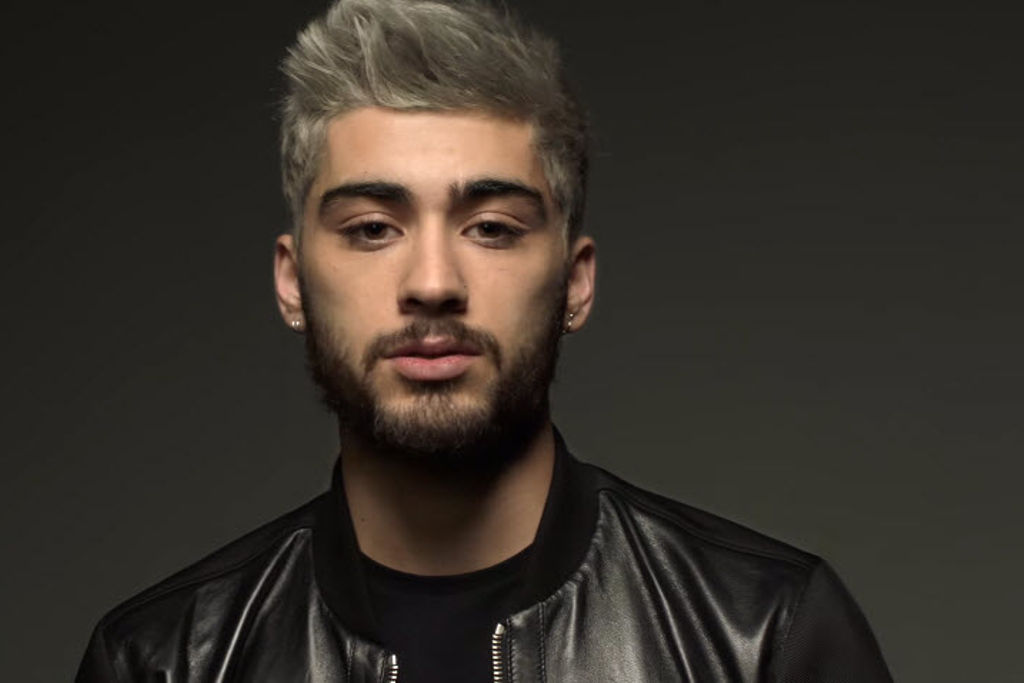

Number Ones: Zayn Malik’s ‘Pillowtalk’ Is The Standard Sexy-Reinvention Single We All Expected

Former boy-band idols have been getting the sexy makeover for decades. Zayn Malik's just the latest.

In his semi-regular column, musicologist Tim Byron takes a deep dive into the new song at the top of the ARIA Singles Chart.

–

Music fans in 2016 live in a ‘poptimist’ age. Cultured young people, these days, are open-minded towards straightforward pop. Twenty years ago, however, such people would have summarily dismissed ‘Pillowtalk’ as corporate garbage churned out to help enslave people to capitalism. The Twitterati were in raptures about Beyonce’s ‘Formation’ this weekend; two decades ago, most of the same kind of folks would have largely ignored a new Whitney Houston single in favour of, say, Sonic Youth or Pulp. In 2005, the famously snobby music website Pitchfork wouldn’t even have bothered to review something like Carly Rae Jepsen’s Emotion; in 2015, their readers rated her album the most underrated of the year.

In truth, though, poptimist music critics and the culturally aware still want very different things in music to the average pop fan. Poptimists, generally, still want the same intelligent, culturally stimulating music their past equivalents wanted when they were Sonic Youth fans. The main difference is that they’re just a bit more willing to find the intelligence and cultural stimulation that might be present in a song by Justin Bieber (and Justin Bieber’s singles of 2015 were actually pretty good in this regard, seemingly largely in spite of Bieber himself).

Of course, most people who listen to songs on the radio — the kind who buy singles or listen on streaming services – aren’t poptimists in this sense. Most people just like what they like without thinking too hard about it. For this reason, the pop charts have long been full of banal shit that most poptimists wouldn’t bother to defend (last week’s #1, a tropical house version of ‘Fast Car’, falls into this category – which is partially why I couldn’t bring myself to write an essay about it).

Similarly, poptimists sometimes champion pop artists that the general public is entirely “meh” about. There’s a subtlety and emotional complexity to Carly Rae Jepsen’s Emotion which clearly appeals to Pitchfork readers, but which has also failed to move the public. This means that there has been an odd dynamic to poptimist writing until recently: you get all these culturally aware people caring about music made by people who don’t care about their fandom. Your average pop star was, until recently, more interested in appealing to the much larger cohort of regular Joes.

But in 2016, the music world seems to have caught up to poptimism. We now live in a thinkpiece age. We’re all well aware that there’s a huge glut of people with opinions on the internet. And pop music is a fun, relatively safe thing to have opinions about. Your opinion about One Direction is a little less provocative, a little less close to your core beliefs, than your opinion about Richard Dawkins.

As a result, this thinkpiece age has changed the kind of pop music that gets made. After all, it’s easier to write thinkpieces about music that does interesting things. Beyonce’s ‘Formation’, and its brilliant video, were made by people very aware of the importance of thinkpieces and Facebook posts and retweets. In 2016, Beyonce could be confident that there would be people on social media, and on websites like Junkee or Daily Life, who would be eager to explain and discuss — and thus disseminate — everything ‘Formation’ represented. All this attention means that pop radio will often be more inclined to play the song – they want to be part of the conversation.

In 1996, if someone like Janet Jackson had released a similar song and video, the mainstream media’s gatekeepers of the time likely wouldn’t have approached the video with the same fervour or understanding that Beyonce has received this week. Whether the regular Joes who are fine with ‘Fast Car’ covers actually like it or not, people with opinions on the internet do now play a role in songs getting heard.

–

Zayn Grows Up: The Sexual Reinvention In Pop

This has been a good thing, from my perspective. The mainstream cannibalises new, different sounds more quickly, more efficiently, and more expertly than ever before. New pop sounds prick up ears in 2016, and that matters more than it used to.

You can hear this in ‘Pillowtalk’, Zayn Malik’s first single since leaving One Direction. It could have been a slightly more adult contemporary continuation of the boy-band sound he got famous with (as Gary Barlow attempted after the break-up of Take That, or as former Boyzone member Ronan Keating did with ‘When You Say Nothing At All’). Zayn could have done a quickie cover to cash in while people are still paying attention to the break-up of the band (as Robbie Williams of Take That did in 1996, with his cover of George Michael’s ‘Freedom’; in the film clip to Williams’ version, he’s actually allegedly miming to George Michael’s version because they hadn’t recorded his pretty desultory cover yet).

Instead, ‘Pillowtalk’ follows the more interesting Justin Timberlake route, because of course emulating JT is the most effective route to success in an attention economy. If you’re a former teen idol looking to reinvent yourself, the reinvention that will get the most attention is the sexual one. Where One Direction were deliberately sexually unthreatening — a perfect receptacle for uncertain, tentative teenage desire — ‘Pillowtalk’ features Zayn singing the word “fucking”.

And Zayn is not using the word as an intensifier. There’s no nudge-nudge-wink-wink here. Instead, Zayn is quite unambiguously singing about acts involving some combination of penises and/or vaginas. If it wasn’t obvious from the title or the rude lyrics, the video features a nude female figure spreading her legs to reveal a flower, and Zayn slobbering over the face of Taylor Swift girl-squad member Gigi Hadid. The whole thing is designed to get people posting things like “omg, this isn’t the clean cut family-friendly dude I remember him being when I was 14!”

Musically, Zayn’s ‘Pillowtalk’ is mostly a cannibalisation of the kind of alt-R&B beats you might have heard on Triple J over the last three or four years. It’s similar to how Justin Bieber’s big singles of 2015 expertly cannibalised a certain kind of previously Triple J-ish dance music; the backing track of ‘Pillowtalk’ could probably pass as a slightly cleaner-sounding backing track to something by fka Twigs, or something off Frank Ocean’s Channel Orange. That slow, syncopated thing with skittering beats is everywhere right now; it’s not a million miles away from Chet Faker or Flume, either.

What mostly makes ‘Pillowtalk’ different to something by fka Twigs is the construction of the melody, and the way that melody is sung, rather than the sounds or the beats. The song soars in the chorus, for example, where the likes of fka Twigs or Chet Faker would deliberately stay icy and tense. It’s unambiguously a pop song despite the alt-R&B beats, and it’s trying very hard to get stuck in your head in a way that fka Twigs and her ilk are not — melodic phrases repeat and recapitulate with a fervour that suggests chart-pop rather than mood music. Zayn Malik’s vocal in the chorus, too, has a soaring tone to it a little reminiscent of Gotye’s ‘Somebody That I Used To Know’.

‘Pillowtalk’ sounds like all this, because those hazy alt-R&B beats currently are the way that pop music denotes sexiness. Barry White and the bow-chick-a-wah-wah guitar are played for laughs these days. For a while there, sexiness in pop did feel like something sweaty at the back of a club at 3am – see, say, Rihanna’s ‘S&M’ – but that phase has passed. Pop sexiness now feels like something a little more slow and sensual, and perhaps a little psychedelically enhanced.

The epitome of the current sexiness is probably Beyonce’s ‘Drunk In Love’ — the one where Jay-Z raps about their foyer foreplay damaging some Warhol art piece he owns. It’s no coincidence that ‘Pillowtalk’ has a reasonably similar beat to ‘Drunk In Love’; it’s also no coincidence that where Beyonce sings about the lure of sex having an effect on her something like drunkenness, the video for ‘Pillowtalk’ is full of psychedelic imagery. If you were Zayn Malik and his (no name) producers, and you were trying to push your sexiness, you’d probably try to sound a bit like ‘Drunk In Love’ too.

–

The New Mainstream: Blurring The Lines Between Pop And Alternative

Because of the alt-R&B in its sound, ‘Pillowtalk’ really does demonstrate how awkward the current era is for an alternative radio station like Triple J. They are not a station who are accustomed to playing songs by former teen idols, Zayn being a former member of One Direction and all. However, because pop music often tries weirder things these days, the difference between typical Triple J fodder and a #1 single by a teen idol is thinner than ever. Most of ‘Pillowtalk’s influences, mentioned above, were played on Triple J.

The Triple J Hottest 100 of 2015 thus inspired a lot of commentary about the bland and unexciting nature of the Top Ten. Some of this was curmudgeonly grumping at KIDS THESE DAYS, but some of it had a point: Triple J’s audience do seem resolutely uninterested in political or social commentary right now. Music that feels remotely transgressive or dangerous or fiercely intelligent sorta seems uncool right now amongst that audience (Kendrick Lamar’s brilliant ‘King Kunta’ very much stood out amongst the top ten for being the exception to this rule). The kids listening to Triple J these days generally prefer chill music to chill to, rather than angry music to rage against the machine to.

Which is to say that there’s little in the average song by Chet Faker or The Rubens that demonstrates any particular frustration with the status quo of mainstream society. I mean, take The Living End’s 1997 hit The Living End’s ‘Prisoner Of Society’, a song that was originally meant as a silly b-side where the band were taking the piss out of punks. It was taken entirely seriously at the time by a very large teen fanbase precisely because its pisstaking accidentally made it such a focused distillation of rebellion.

And Triple J, by being the main radio station where this large teen fanbase could get its rebellious jollies, gained a certain power by playing rebellious music like ‘Prisoner Of Society’; Triple J seemed full of very popular music that pop radio wouldn’t have touched with a ten-foot pole. The Rubens or Chet Faker, in contrast, are mostly just a little weirder and less hook-focused and vocals-focused than typical mainstream stuff. And so when mainstream stuff gets a bit weirder, there’s often not that much room for Triple J’s current crop of music to move.

Perhaps for this reason, ‘Pillowtalk’ – a #1 single by a former One Direction member – feels noticeably more provocative and more dangerous than the Hottest 100 winner, The Rubens’ ‘Hoops’. ‘Hoops’ feels like it was everyone’s seventh favourite song. It’s little more than a well-crafted, catchy little no-frills pop song. There was no wheel reinvention in ‘Hoops’, no butterflies broken upon the wheel, no sense that the wheel’s on fire. It’s just a professionally made, reasonably-priced wheel. It’s the wheel you’d probably buy when it was time to replace the previous one and you just wanted something that would work smoothly.

The only thinkpiece that it’s possible to write about ‘Hoops’ itself is basically a complaint about how ‘Hoops’ is too boring to inspire thinkpieces (yes, The Rubens are yet more white dudes winning the Hottest 100 – I mean the song itself). Perhaps this boringness is exactly the point. After all, the point of the alternative is to, well, be an alternative. And if the mainstream is all loud flashy thinkpiece-bait, then it’s no surprise that the alternative has started to avoid making a big scene. Perhaps the pragmatic, functional, slightly introverted white-dude boringness of ‘Hoops’ really is the alternative these days.

Which is not to say that ‘Pillowtalk’ is reinventing the wheel either; it’s the obvious move from the former boy band member in 2016. It honestly sounded exactly like what I was expecting it to sound like before I’d listened to it. Which means it’s not quite as inspired as it should be, and so — unlike Bieber’s hits – will probably have trouble crossing over to outside the fanbase. ‘Pillowtalk’ is just a serviceable, professional reinvention of Justin Timberlake’s wheel, updated to reflect new trends in wheel design.

–

Tim Byron has written for Max TV, Mess+Noise, The Guardian, The Big Issue, and The Vine. (@hillsonghoods)